This is a tale of two men on very similar, but ultimately different paths.

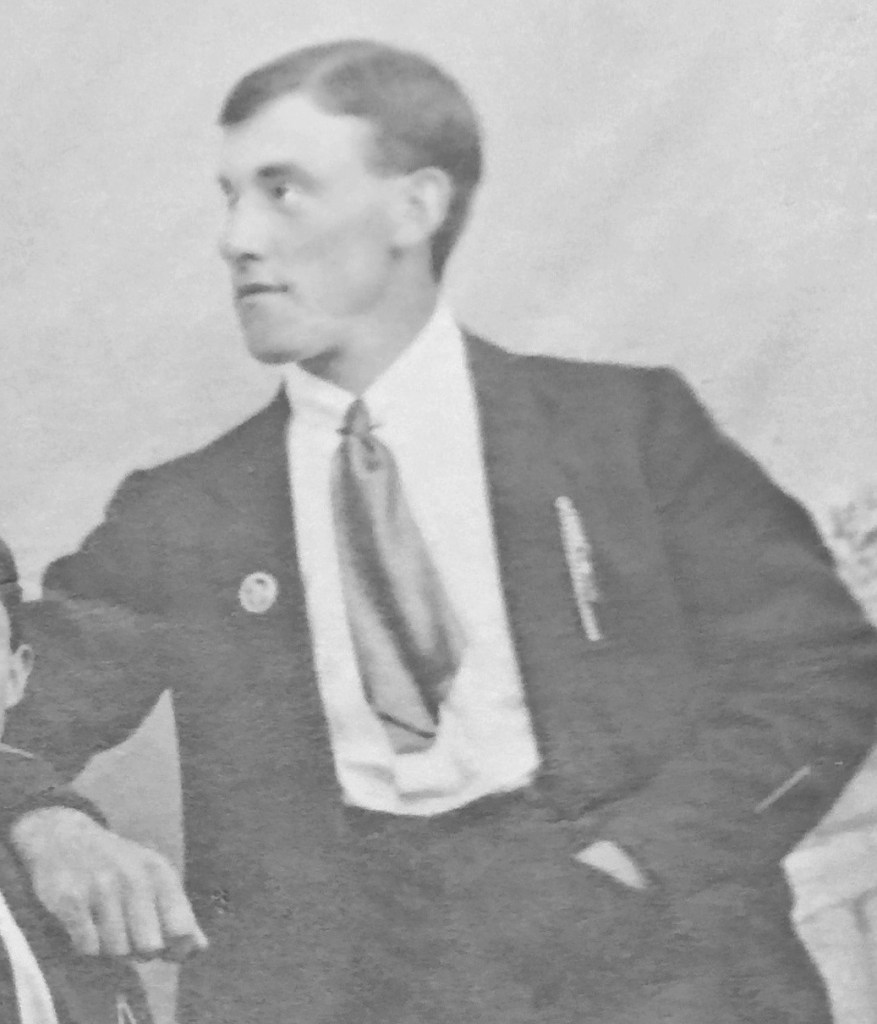

My very first blog, which seems like a long time ago now, was written about my great uncle Harry Crook.

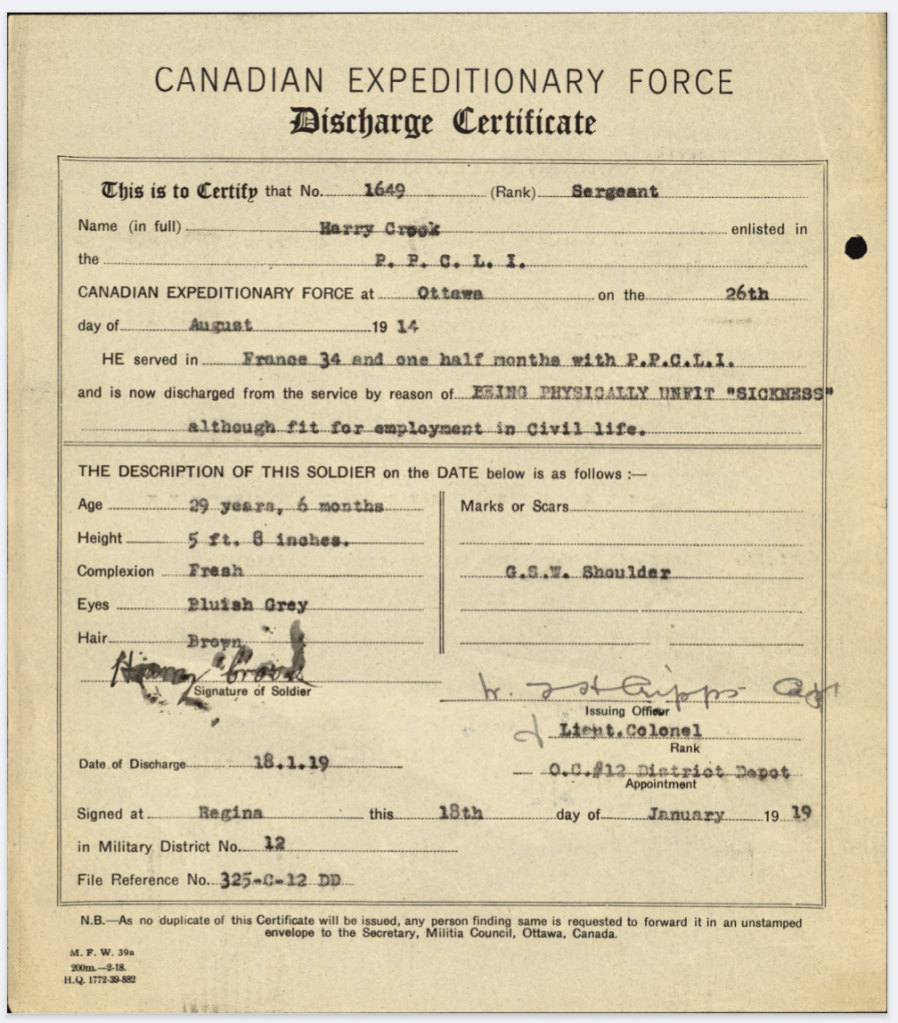

Harry had been a career soldier, serving with the Royal Garrison Artillery for almost seven years, before becoming an émigré to Canada in 1913, and then re-enlisting in August 1914 with the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry on the outbreak of war.

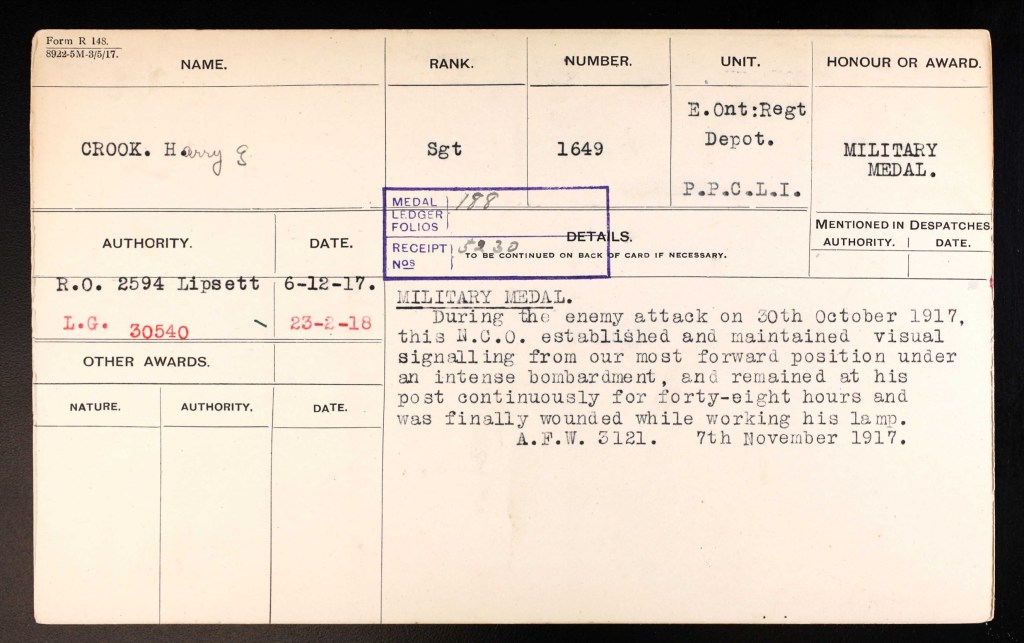

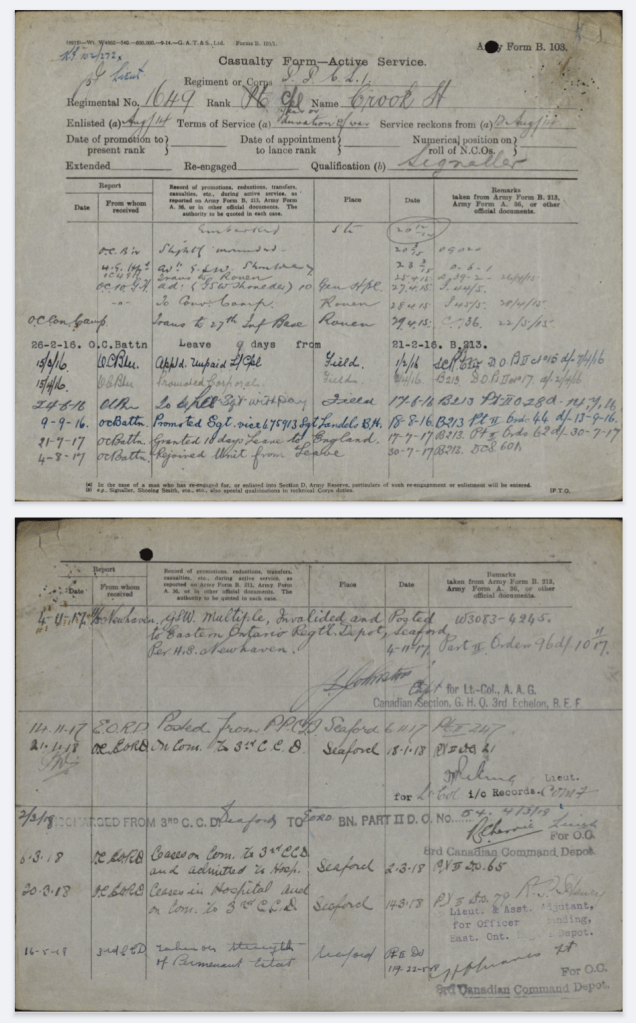

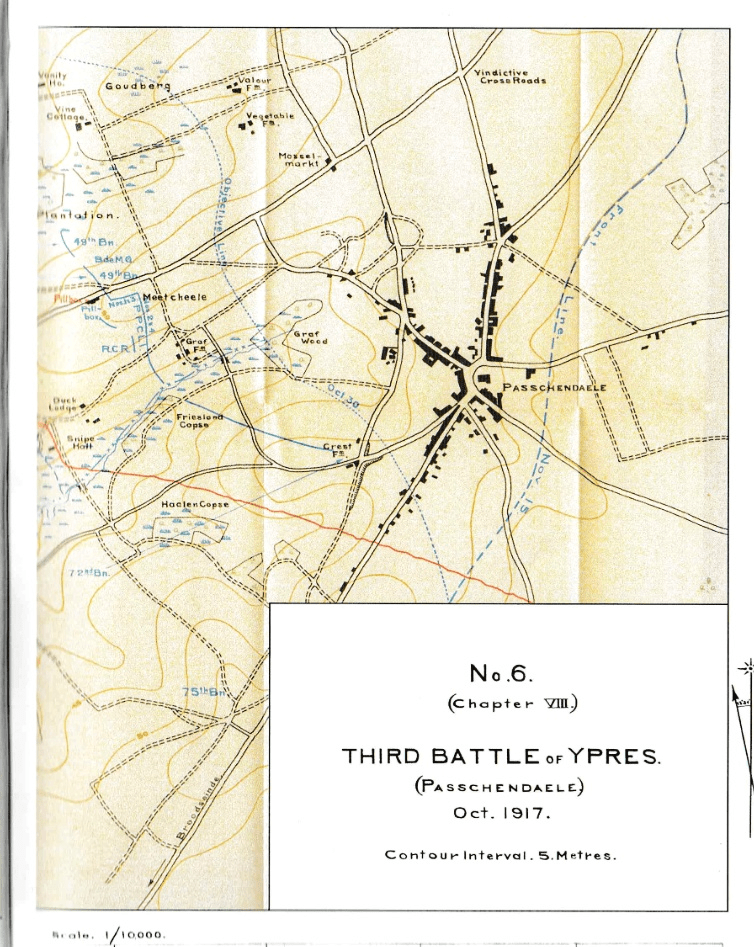

As a Canadian soldier, Harry had been relatively easy to research and, as with most men who served with their expeditionary force, has a complete service record that documented his time with them in great detail. Helpfully, his regiment also has a detailed official history, and their war diaries are fully transcribed and online, meaning pretty much everything there was to know about Harry was there at my fingertips, right down to the grid reference and exact time that he was hit by a shell near Passchendaele in the action that would win him the Military Medal and end his time at the front.

I thought I knew everything useful there was to know about his war; but there’s one thing I have learned in this game of family history: it’s that there’s always one more fact to find…

Archives are continually updated and reorganised, and even when there are no new sources, I occasionally re-search the usual places to see if there’s anything new to find, or a different angle to look from. It was on one of those browsing sessions that I realised that a man filed as ‘Crook, E’ was actually uncle Harry, and that it would uncover a completely new chapter in Harry’s wartime story.

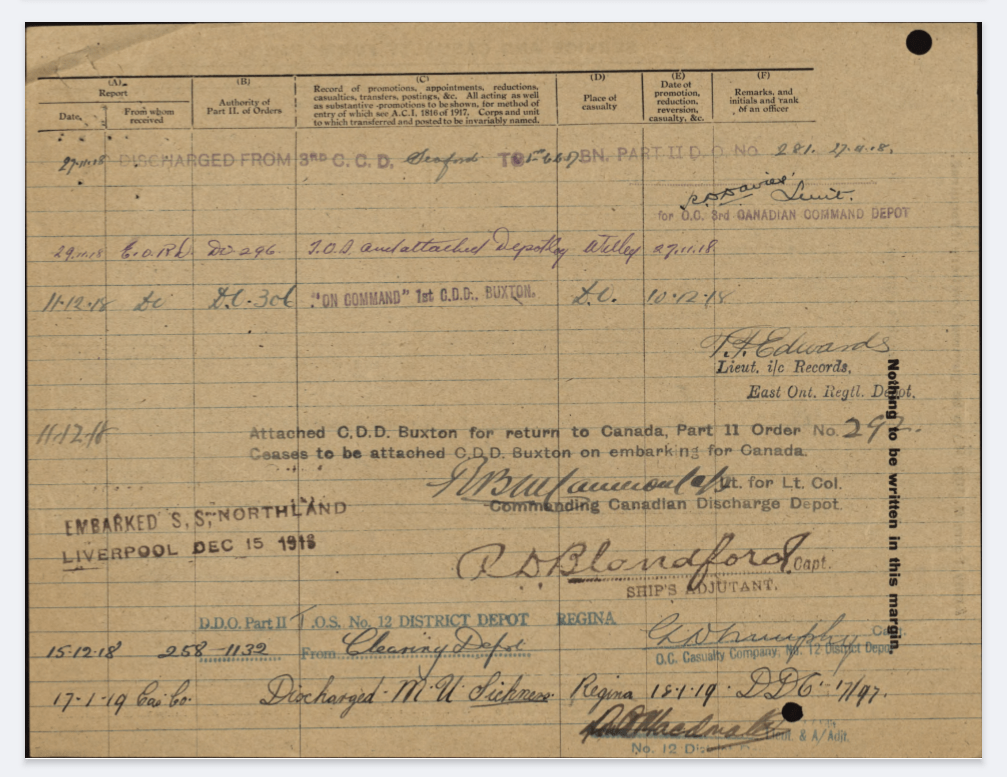

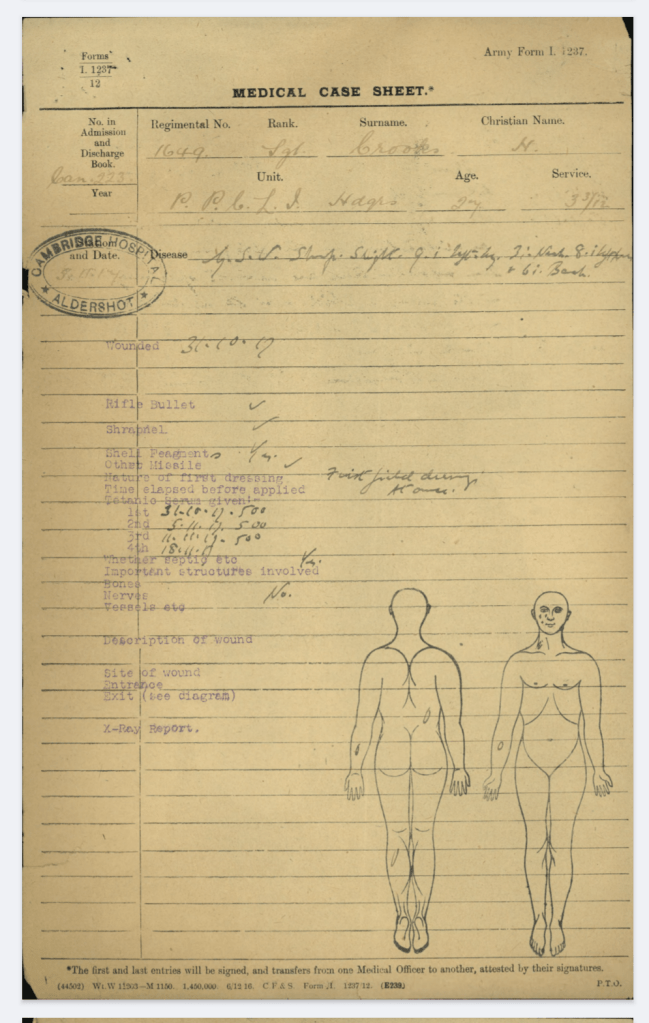

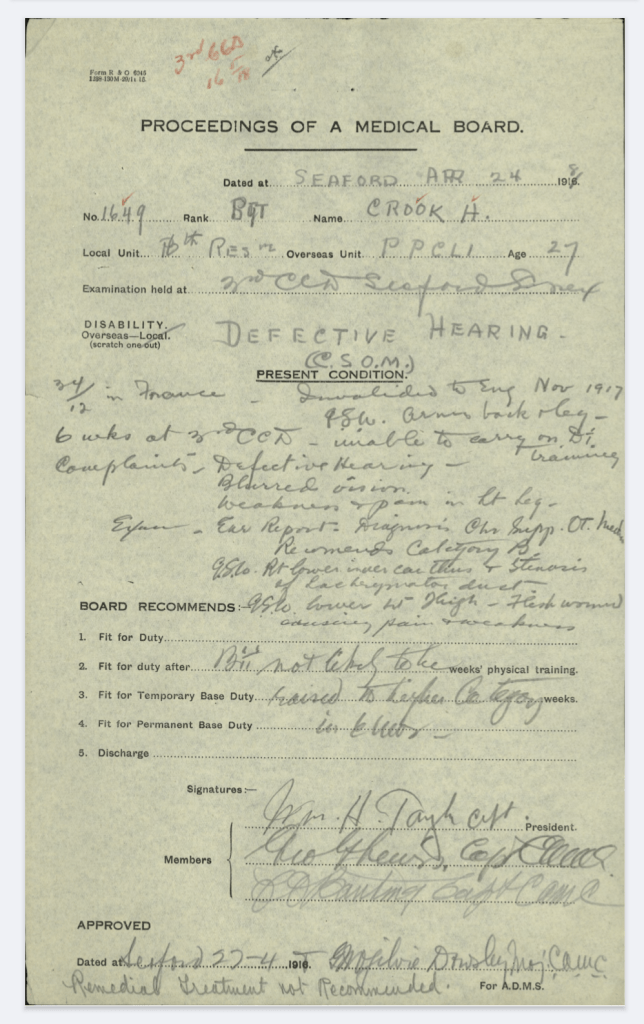

Such is the detail in the Canadian records, we know that from the point he was almost blown to bits at Passchendaele at the end of October 1917, Harry was very quickly processed through the hospital system back to England and posted to the 3rd Canadian Command Depot at Seaford, in Sussex. Harry spent most of 1918 there, until he was finally repatriated to Canada in December of that year.

Suffering from multiple shrapnel wounds and damaged hearing, I’d assumed that he’d simply been recuperating, and deemed unfit for frontline service – but hidden in the archives was something previously undiscovered by me, and perhaps explained by his condition.

All of the above files give you the flavour of Harry’s service, injuries, and finally, discharge in 1919. When you take into account his exemplary service and faithful dedication leading up to his award for bravery, you might have an image of a man as a professional soldier and senior NCO unlikely to be subject to military discipline.

You’d be wrong!

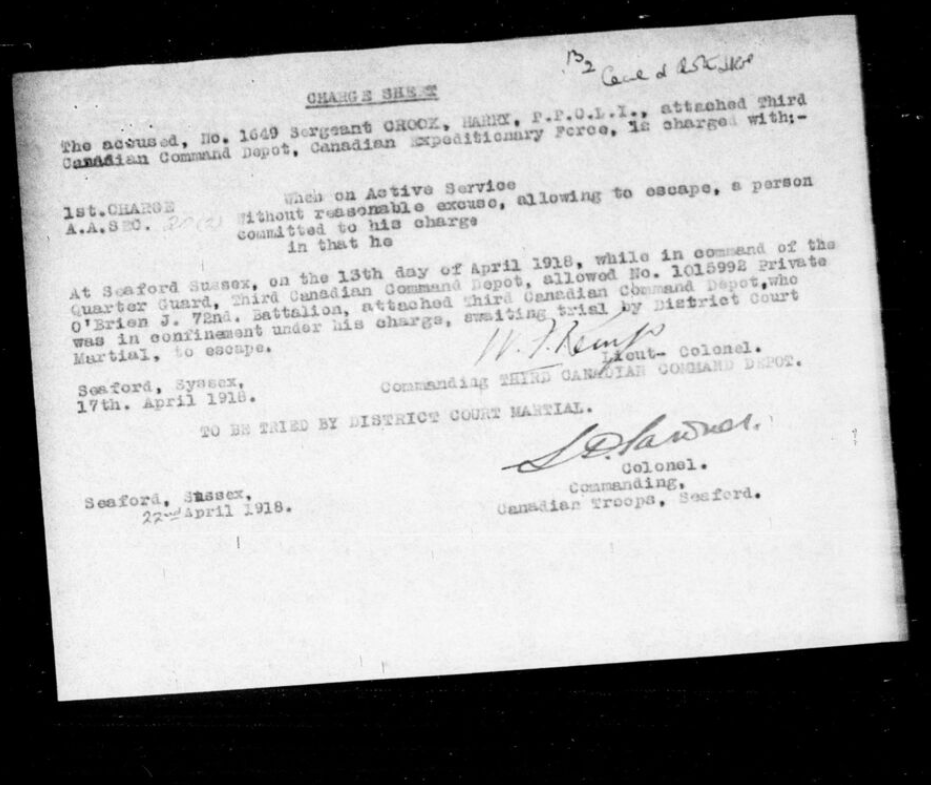

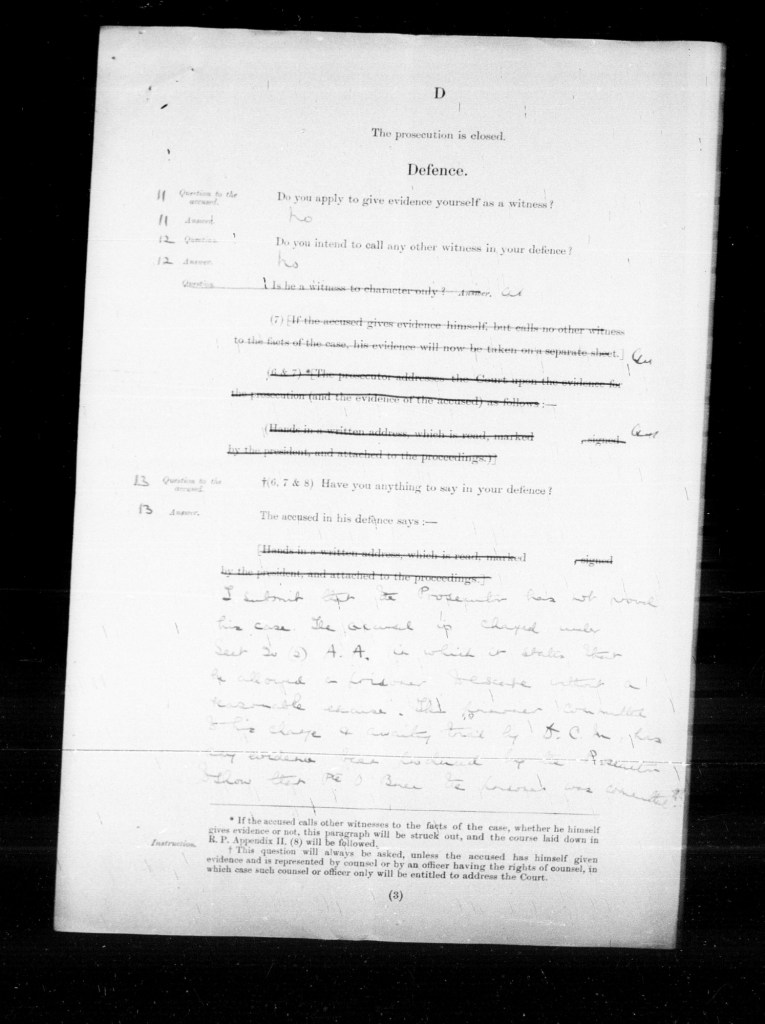

I have to say I was surprised to find that Harry had been subject to Court Martial for neglect after his path crossed with that of another man, a soldier with an entirely different track record, but linked by circumstances.

Filed away under ‘Crook, E’ in Court Martial records is the tale of how another Canadian soldier under the detention of the military authorities for being absent without leave, was allowed to escape, and how Harry got the blame. At least temporarily.

The record that is the ‘Ministry of the Overseas Military Forces of Canada : Courts martial records, 1914-1919’ is an almost impenetrable source of information that defies logic when it comes to its filing system. But, with a bit of advice, I soon unraveled the facts.

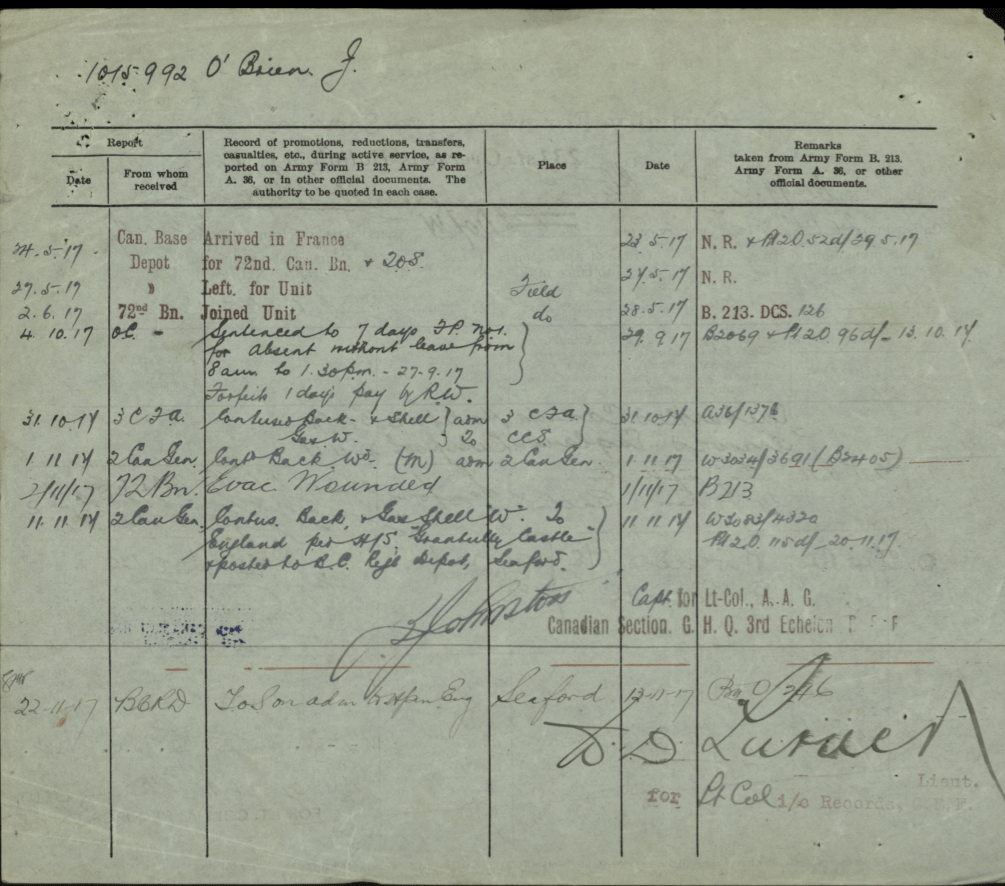

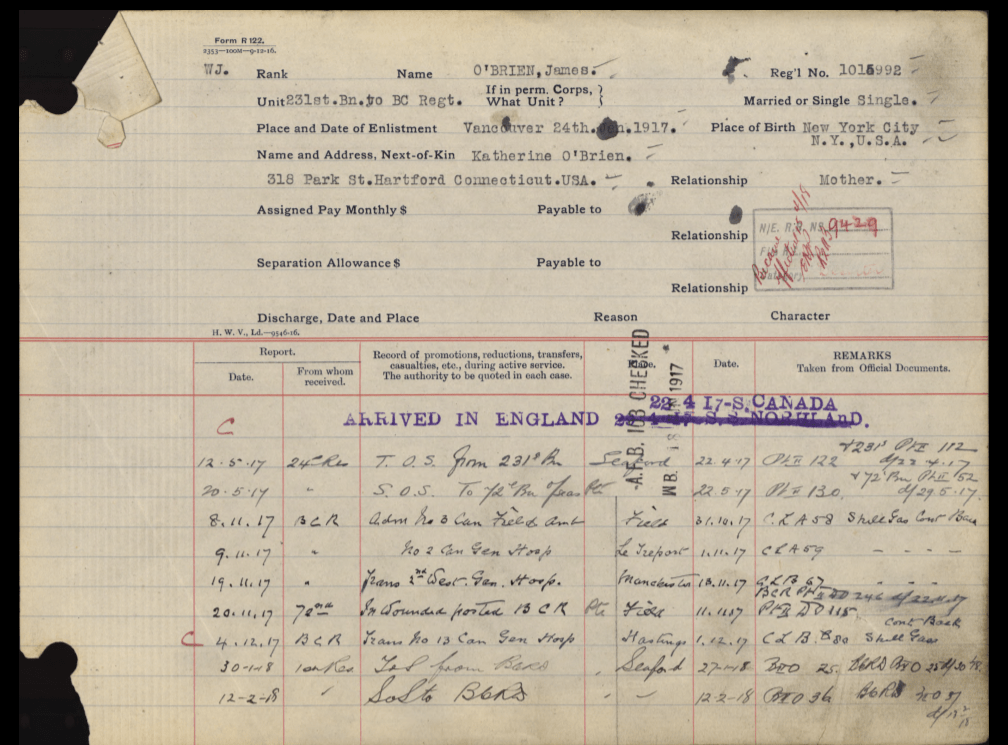

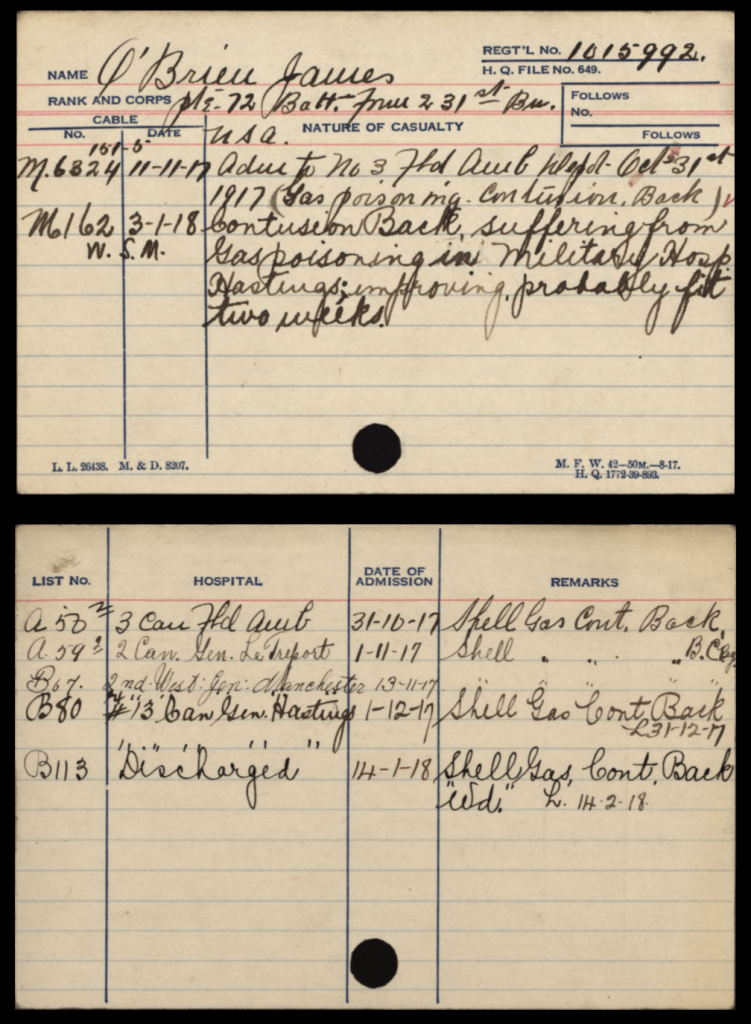

Private James O’Brien

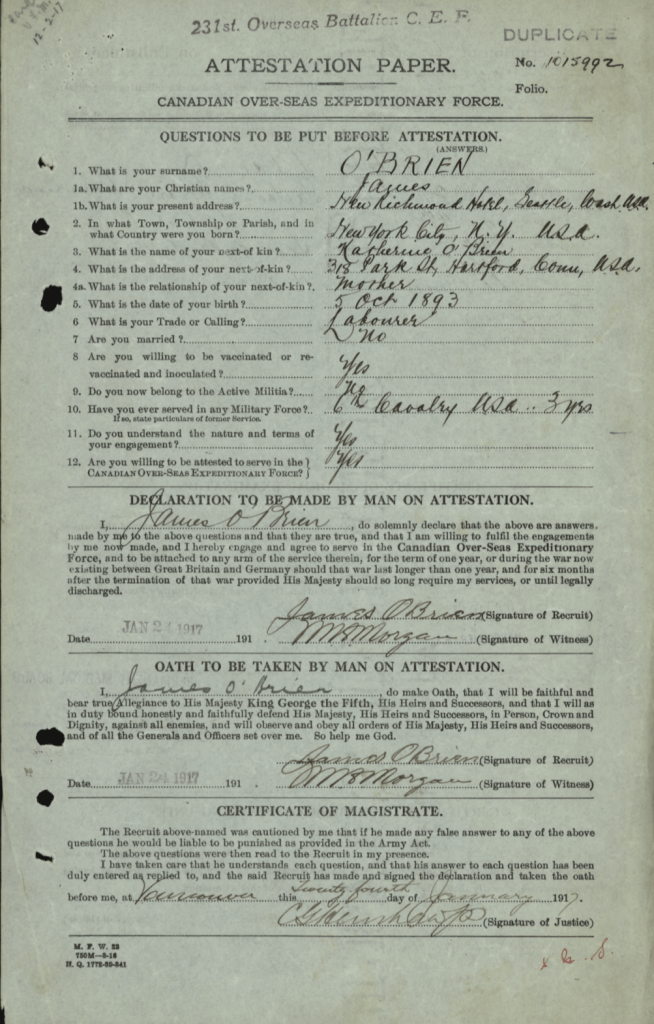

James O’Brien was an American, originally from New York City, but living in Seattle in 1917.

Born in October 1893, on enlistment with the 231st Battalion (Seaforth Highlanders of Canada) in January 1917, he claimed 3 years previous service with the U.S 6th Cavalry, so apparently had some experience of military life.

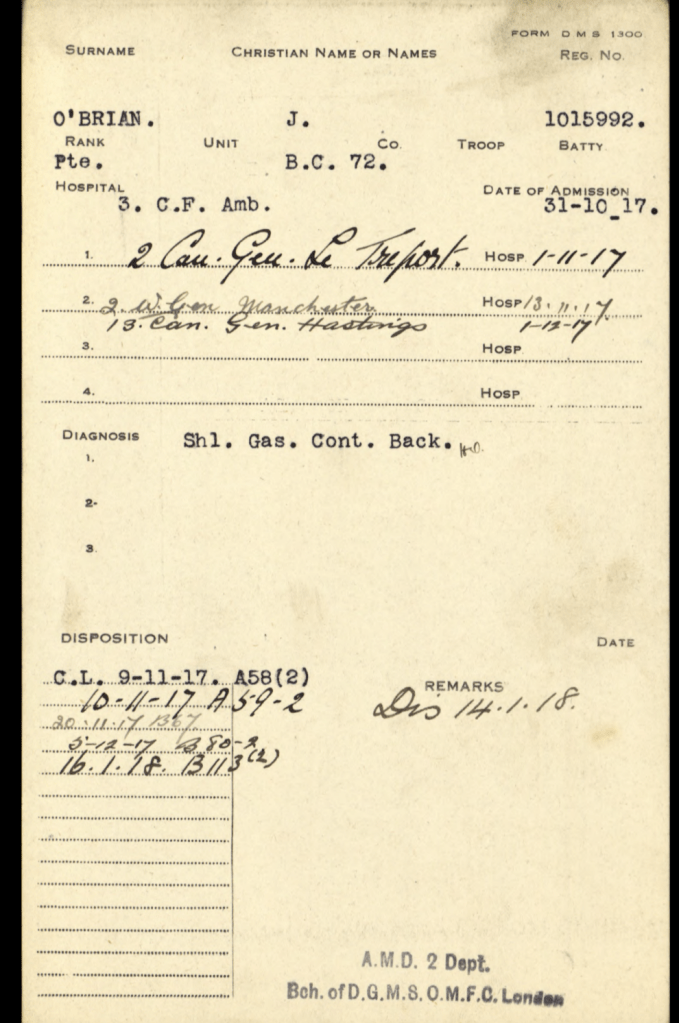

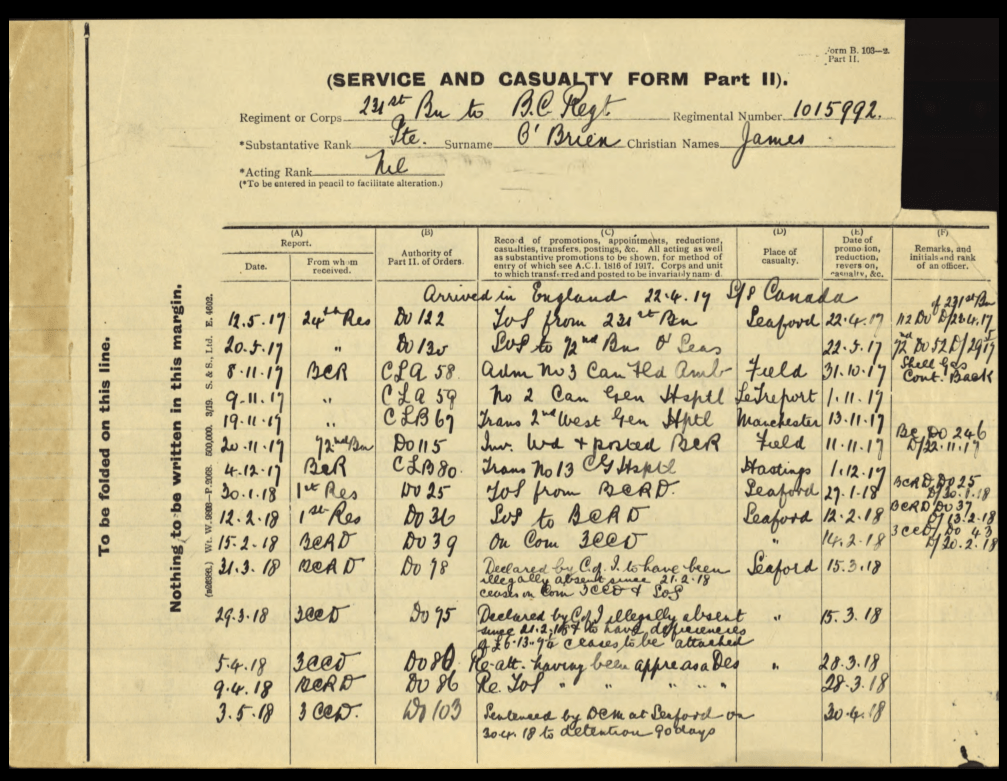

To cut a long story short, James found himself in France in May 1917 having passed through the 24th Reserve Battalion to join the 72nd Battalion (Seaforth Highlanders), and to fast forward even further, then found himself on the opposite side of the Ravebeek to Harry at Passchendaele, wounded by gas shell on the same October day that Harry was wounded a few hundred yards away.

Two men, linked by circumstances.

The 72nd Battalion were involved in the fabled assault on Crest Farm – scene of many heroic deeds by the Canadians and site of an impressive memorial to their losses and combined efforts; but James O’Brien had by then already crossed swords with military justice, having been punished for being absent without leave for a few hours just a couple of weeks earlier.

Evacuated to England with contusions to his back and suffering from the effects of gas, James would soon find himself at 3 C.C.D at Seaford with Harry, albeit with an entirely different outcome.

Via hospital at Hastings, it seems that James was soon AWOL again and was apparently on the run from 21st February until apprehended on 28th March. He then found himself awaiting justice at Seaford, until 13th April when he slipped away, again. He was at large for four days.

This time, Harry was in the spotlight.

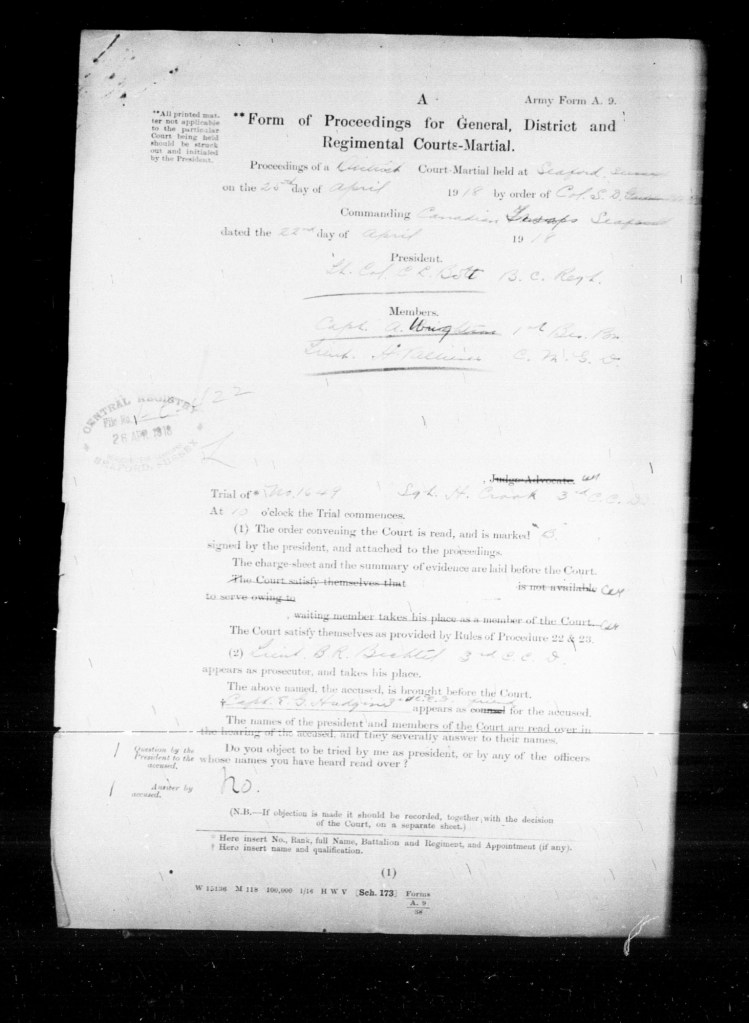

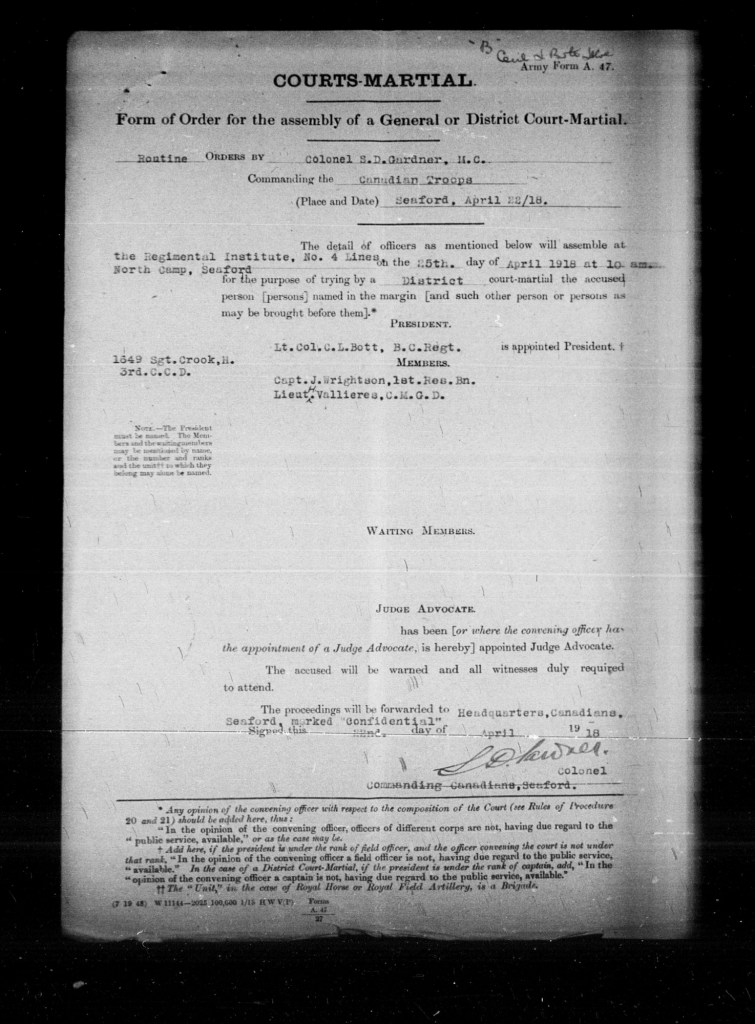

The Trial

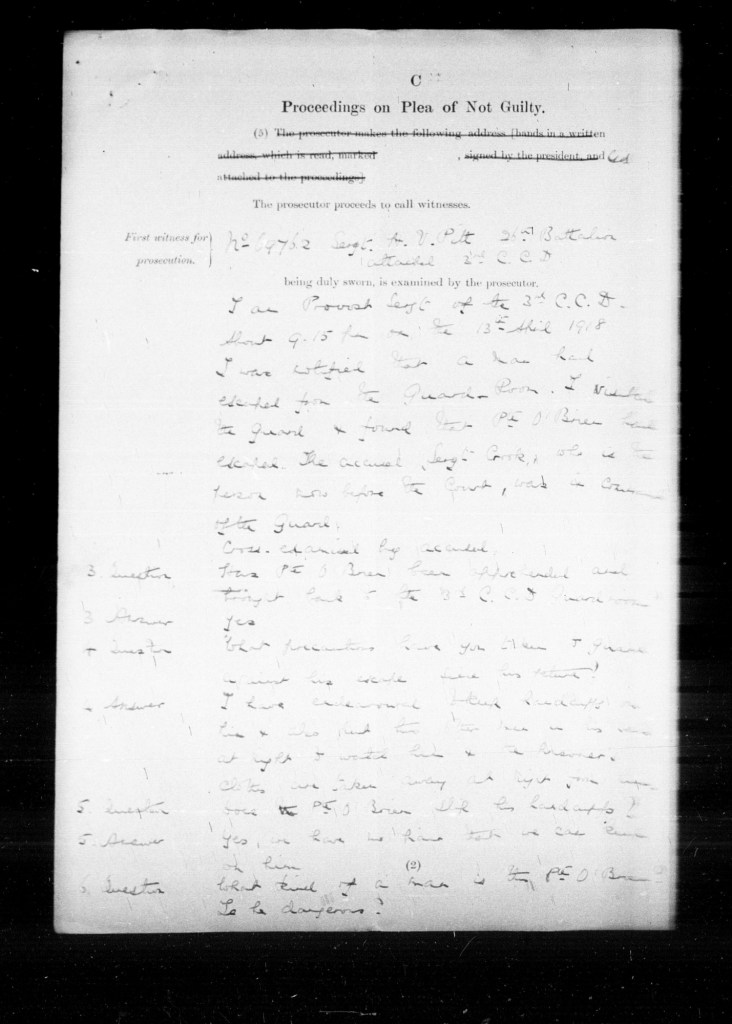

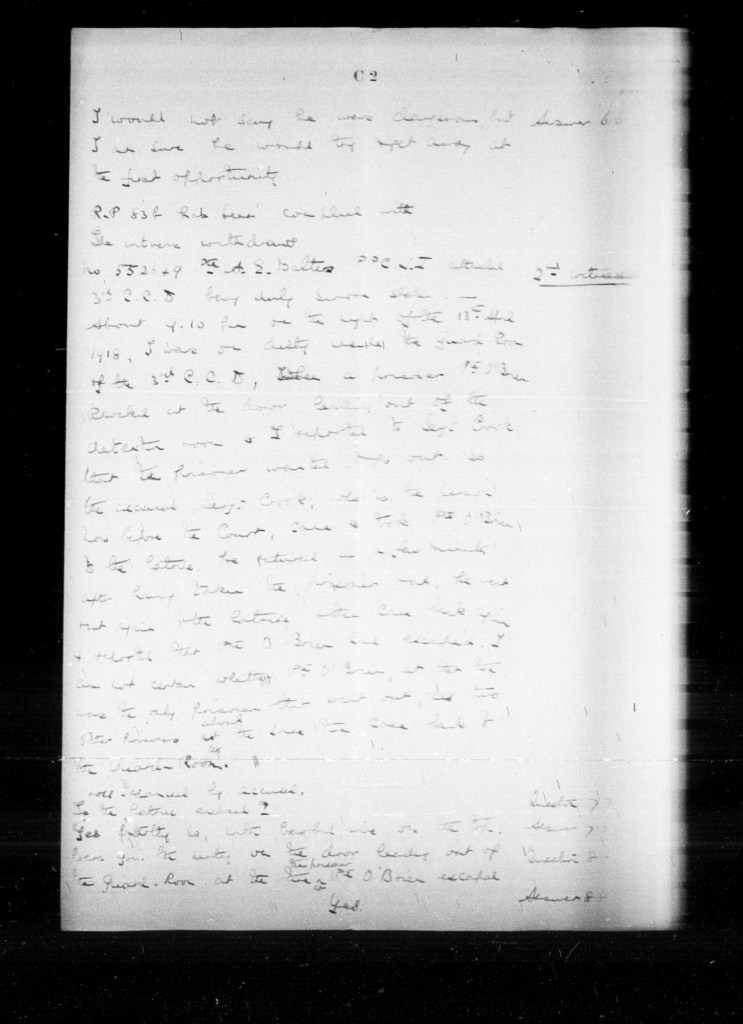

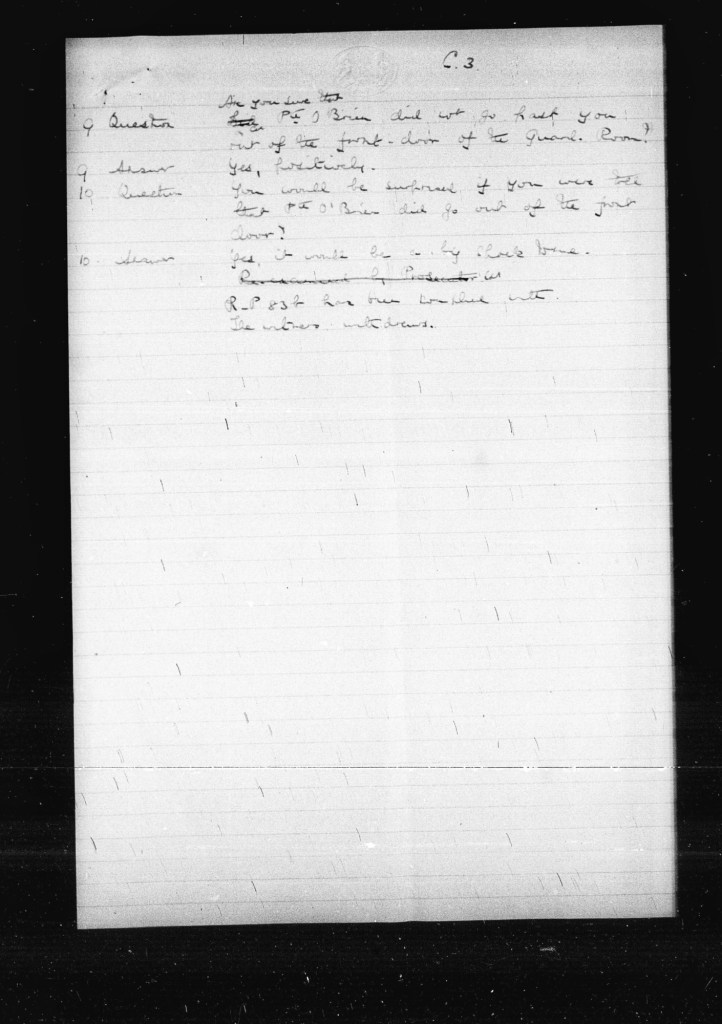

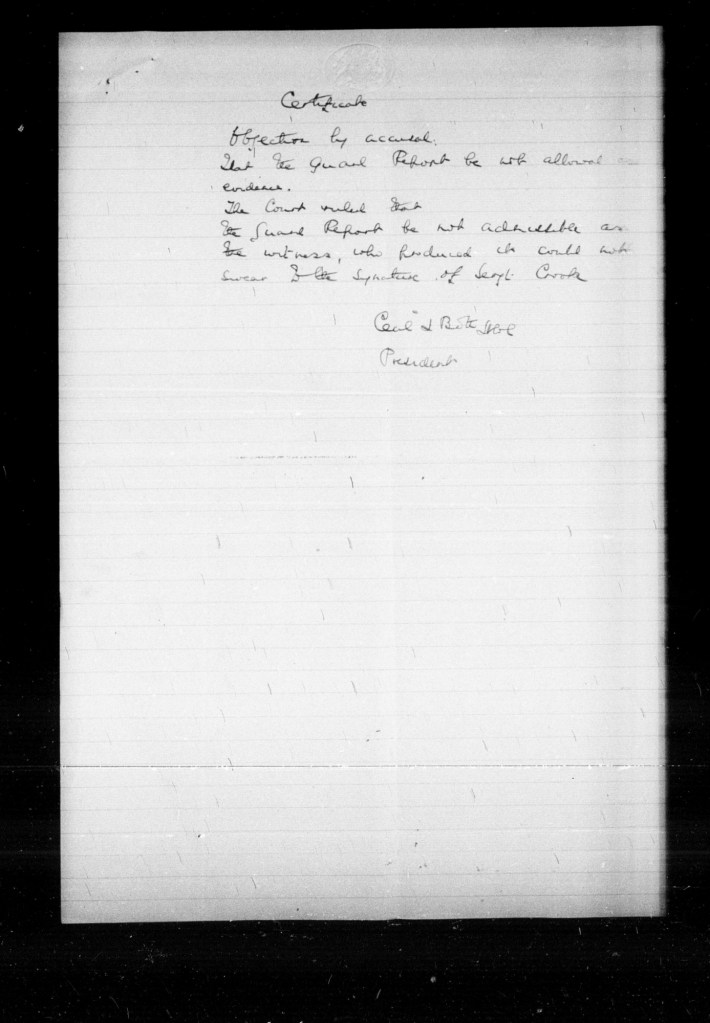

It seems that when James O’Brien was noticed as missing, Provost Sergeant Harry Pitt noted that Harry had been in charge of the quarter guard at that point. The files are difficult to read but it seems simply that being in charge was enough to put Harry on the hook when the elusive Mr O’Brien seems to have simply walked out of the guard room front door, unchallenged.

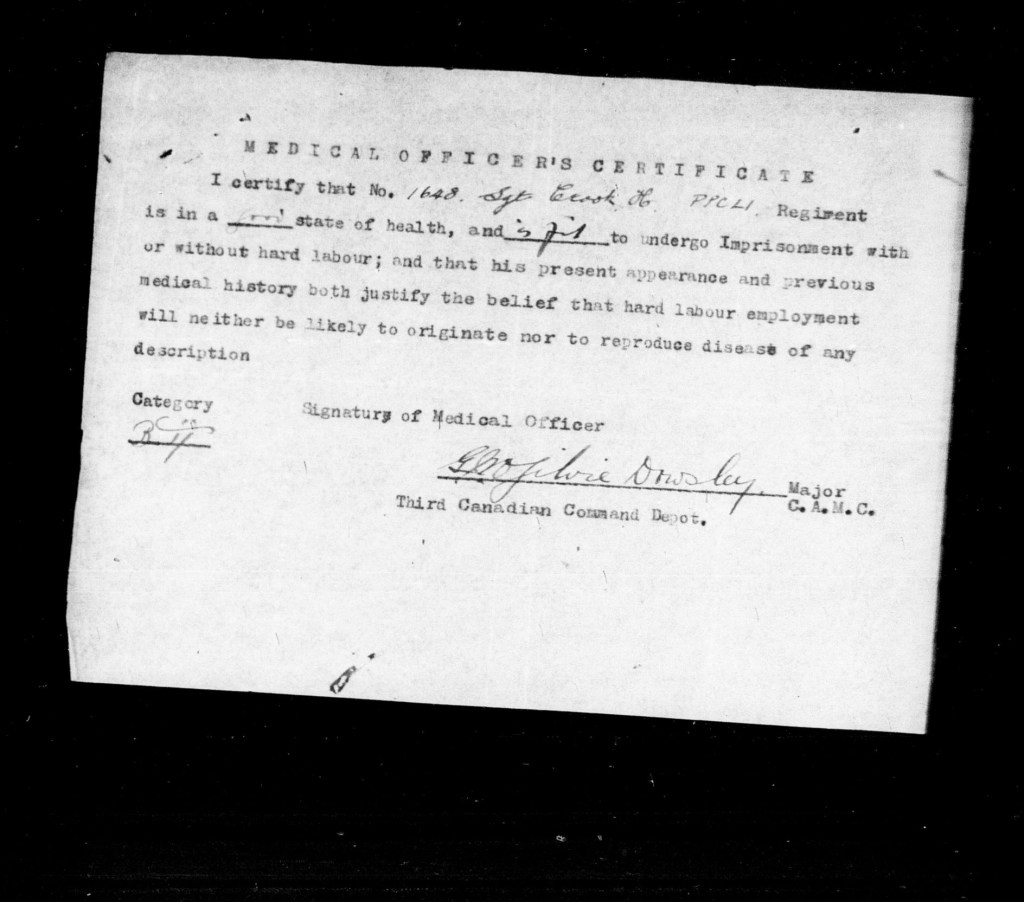

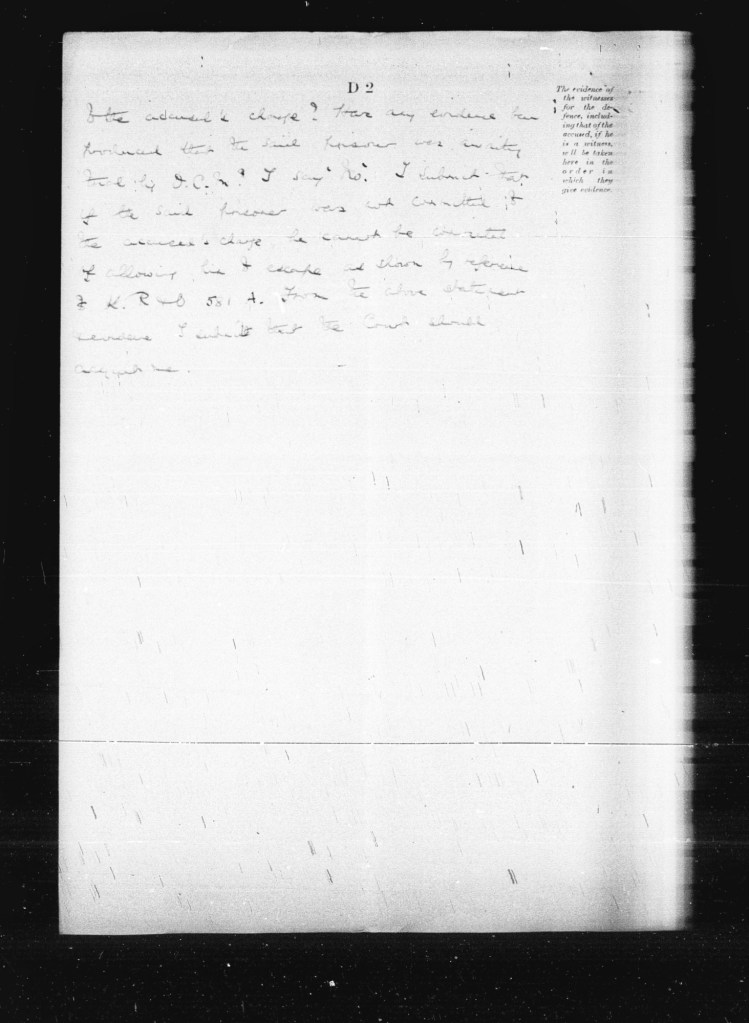

Now I don’t know if Sergeant Pitt was a jobsworth, or if a slightly deaf and shrapnel riddled Harry was off his game, but the result was Harry was now on a ‘fizzer’ and charged with allowing a man to escape. Either way, Harry was deemed medically fit to face the consequences, although being a bit fuzzy after recovering from shell injuries doesn’t appear to have formed part of his defence. His medical report above, which is contemporary to the incident shows he had defective hearing, blurred vision and weakness and pain in his right leg, so he seems to have been barely fit enough to be in charge of the guard.

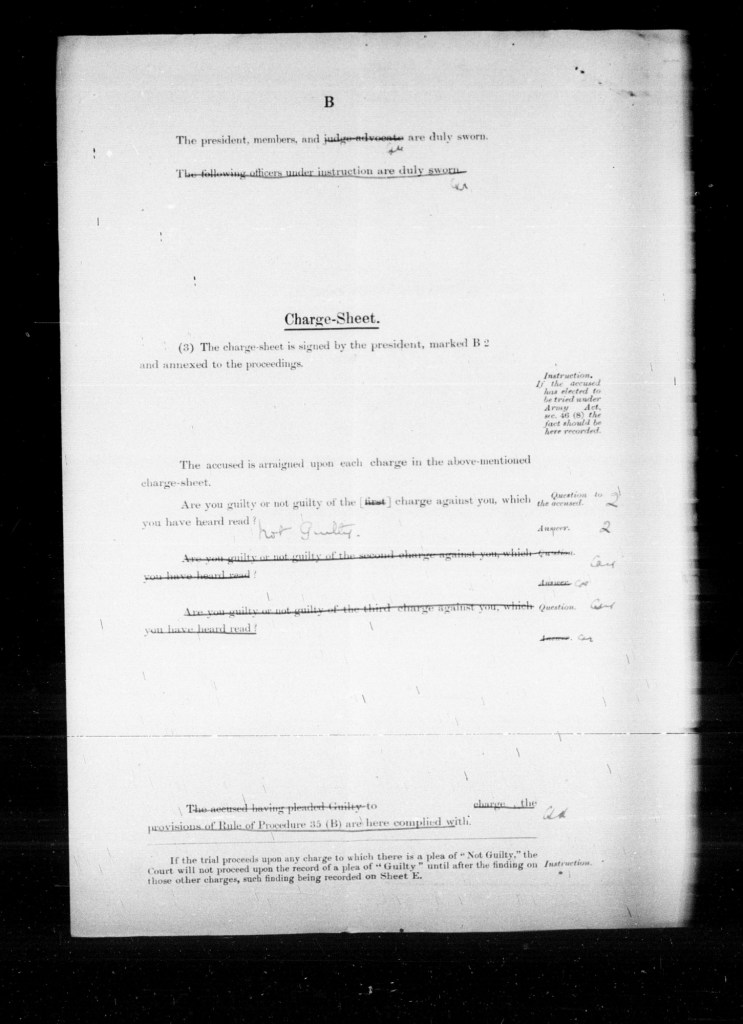

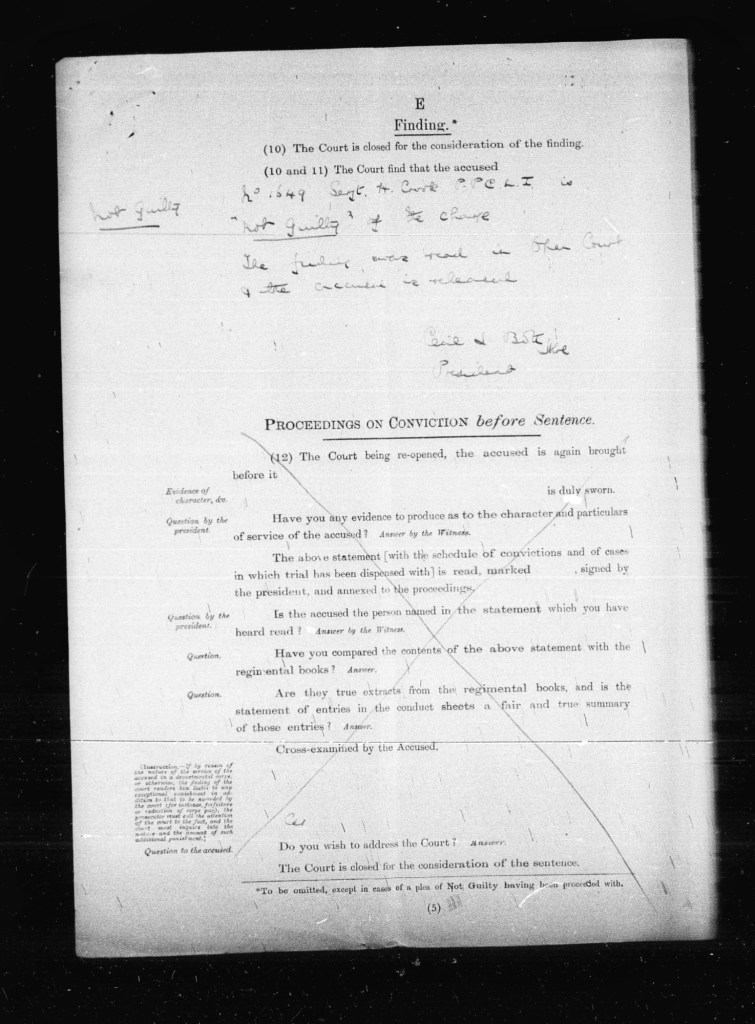

The papers below tend to suggest it probably took 15 minutes for the panel to decide that Harry wasn’t to blame, and he was acquitted.

As you can see from the records, Harry served out his time in England and was back home in Canada at Christmas 1918, before being discharged in January 1919.

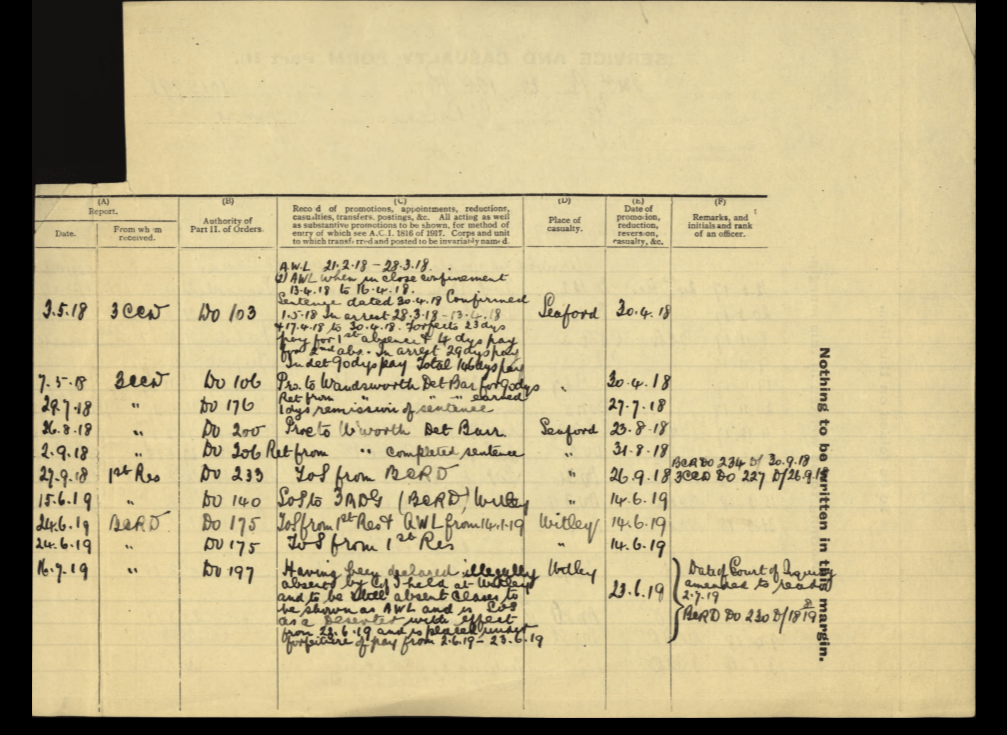

On 30th April 1918 James O’Brien received 90 days detention and deductions of pay for his illegal absences, serving out his sentence at Wandsworth Detention Barracks. He remained ‘on strength’ until the following summer. There are other stories to be told about the Canadians in England at the end of the war, including unrest and disobedience in the camps as men waited to be shipped home, but suffice to say life was tough and unhappy for Commonwealth soldiers, even after hostilities had ended.

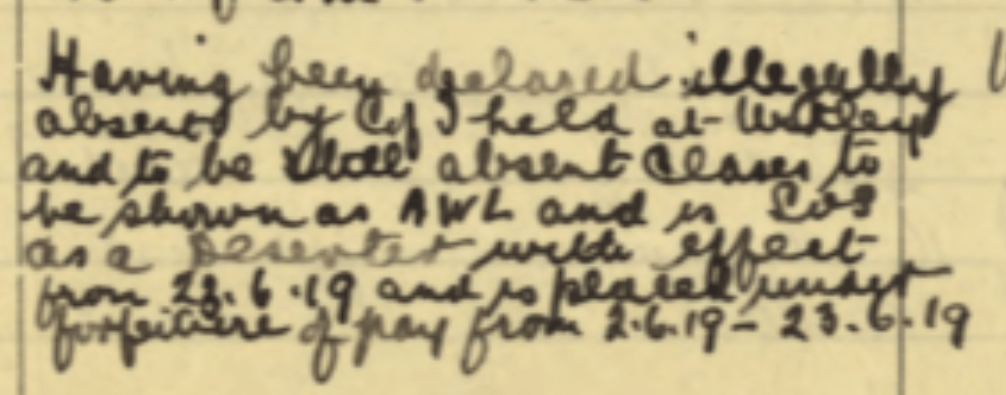

We’ll never know what motivation James for going missing in France, or for the repeated absences in England, but when he was finally discharged in July 1919 he was already absent again and listed as a deserter.

It seems that rather than pursue him one more time, his pay was stopped and he was struck off strength after being missing for a month. I haven’t researched him to find out what became of in him in later life.

So there we have it – a new insight into the war of Harry Crook and a story about another man who served alongside him for Canada, but whose experience was entirely different.

Both very nearly paid the ultimate price for their service.

Harry was a proud, decorated military man. Maybe James O’Brien was a coward, or simply not cut out for military life. Or maybe he was just scared witless by his experience at Passchendaele and couldn’t face the trenches again. It’s notable that in the January medical notes on his file, he was expected to be fit within a couple of weeks. Perhaps the thought of having to go back is what precipitated his absences in the February and thereafter. Around 2,200 Canadians were charged with desertion, and another 3000 with being AWOL. Twenty five Canadian men were executed, but I’m certain that James O’Brien didn’t go missing in the face of the enemy, so was never in the most serious category.

We’ll never probably know his reasons, unless someone decides to research him, or like me, stumbles across other facts hidden away deep in the archives.

And that’s why I keep looking.

Wonderful reading Dave. You excel yourself! How true that in this game of family history, there’s always one more fact to find… I have found this time and time again!

LikeLiked by 1 person