“Through Fire We Conquer”

A 75th anniversary approaches.

Fresh on the heels of the centenary of the Armistice and the ending of the Great War – the ‘war to end all wars’ – our eyes are now lifting towards the Second World War and another history.

Already the internet and news is filling our minds with memories of the summer of 1944 and hashtags such as #DDay75 bring our focus to the Normandy landings and the allied push to victory on land in Europe. For a generation, the nation struggled with the legacy of Bomber Command. Much as trench warfare was debated under Haig in the First World War, and set against the glory attributed to the D-Day landings, the tactics of bombing and it’s effects on civilian populations proved controversial, and in many ways overshadowed the bravery of those that flew.

In 1940, Winston Churchill said:

“The fighters are our salvation but the bombers alone provide the means of victory”

This is the brief tale of one mans small part in the efforts of RAF Bomber Command to wrest back control in the lead up to the land victories that ended the conflict. For this story, I switch to my wife’s family history, and the subject is her paternal great-uncle ‘Jack’ Pearce. Without writing an entire book about Jack, this blog sets out the events surrounding a remarkable story which unfolded in May 1944.

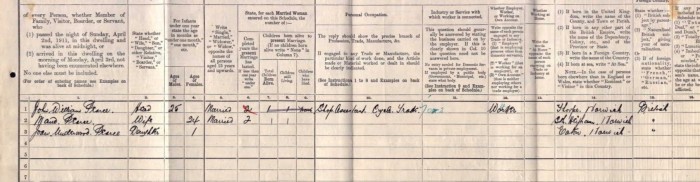

John Goffin Pearce was born in April 1914 in Norwich to John William Pearce and Maude Nicholls. While John is clearly from Norfolk stock, over time I’d bounced his name back and forth with his son (also named John) to confirm his origins. We’d been aware of a knowledge gap in his history, but the power of the internet eventually identified his heritage. We’d contemplated the uniqueness of his middle name ‘Goffin’ and surmised that it was probably linked to the Huguenot migrations to England from France in the late 1600’s or early 1700’s, due to its prevalence in France and the Low countries. We then identified that the Pearce line had crossed with the Goffins in the mid 1800’s. Surprisingly, this then led us down a Goffin rabbit hole to a long-established Norfolk Goffin line inhabiting the villages of Broadland east of Norwich, tracing way back to the village of Stokesby near Acle in 1488. But that, as they say, is another story.

The Pearce Family, 1911 Census

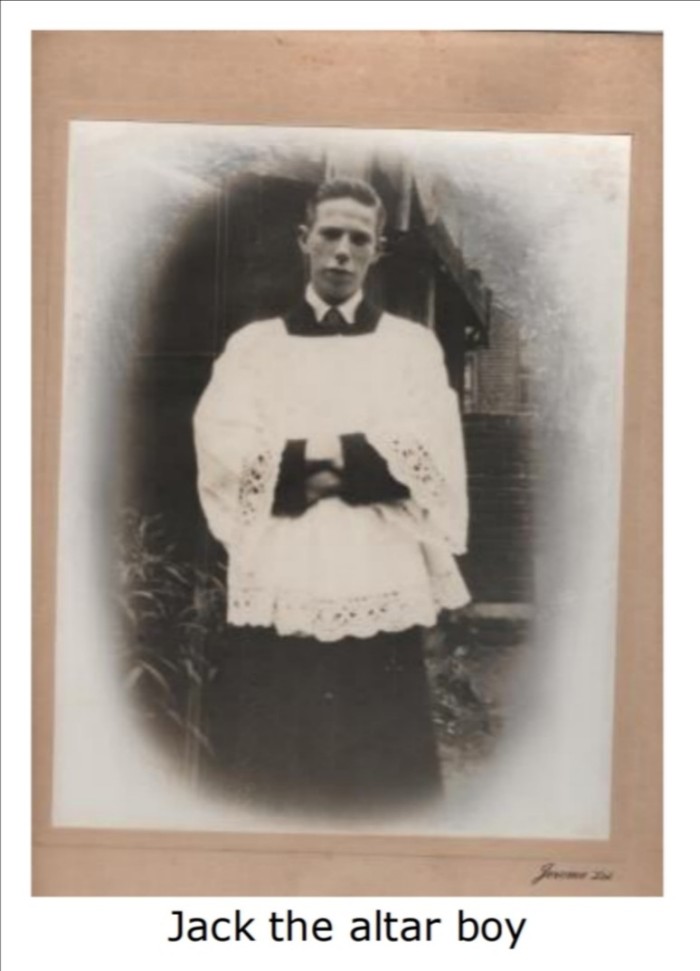

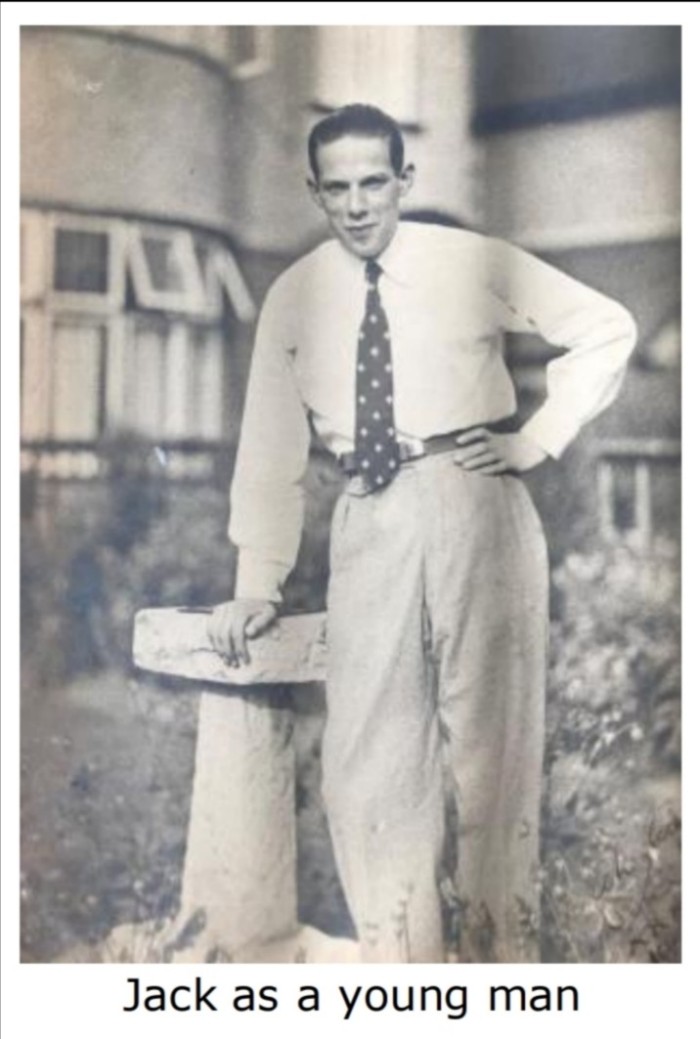

Jack grew up in Thorpe St Andrew, Norwich and became a printer by trade, pre-war working for Her Majesty’s Stationary Office. He was an altar boy at the churches in Norwich including St John’s Maddermarket and St Peter Mancroft; he studied Greek and Latin and considered the priesthood as a vocation; a devotion to the church that would continue into later life.

So how did Jack’s military journey begin?

On June 4th 1940, Jack joined the RAF Volunteer Reserve. I have no details of his early service, or how soon after registering he was called into service, but the family history suggests he was in India, and was near Singapore before it fell in February 1942. He holds The Burma Star, so any service in that theatre must have been after December 11th 1941.

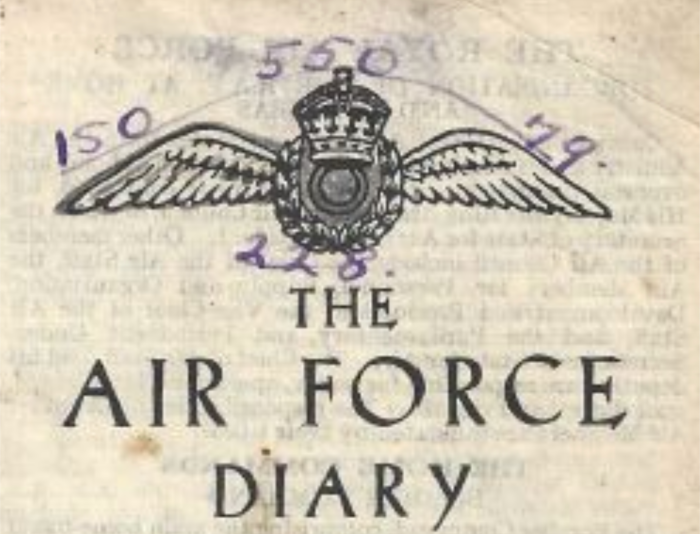

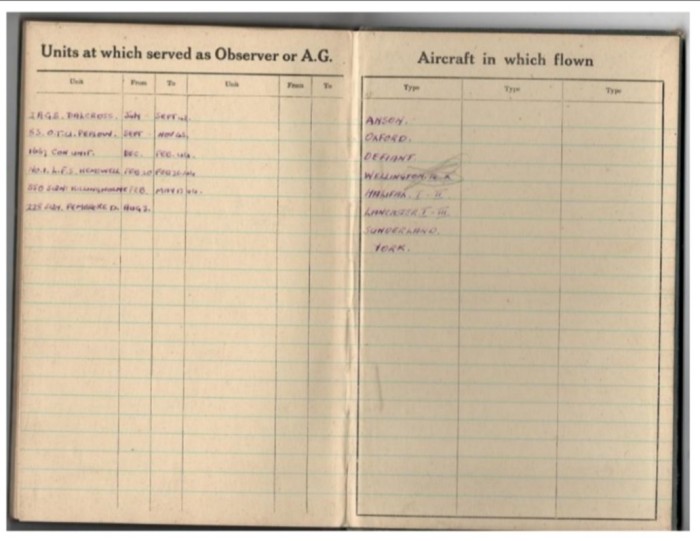

Jack’s 1944 Air Force Diary is annotated with what appears to be squadron numerals.

Jack would then find himself back in England and from late summer 1943 would train to become an air gunner on Lancasters.

His logbook places him at 2AGS at Dalcross (Inverness), he then passed through 83 Operational Training Unit at RAF Peplow in Shropshire – a Wellington training unit, and also RAF Faldingworth in Lincolnshire with 1667 Heavy Conversion Unit for Halifax/Lancaster’s in late 1943.

It’s not clear when Jack could have served with 150 Squadron, nor 79 Squadron which was a fighter squadron (although this could account for his Burma Star as they were in India).

After that he appears at RAF Hemswell, near Gainsborough, which was home to No.1 Lancaster Finishing School for training aircrew on the new Lancaster heavy bomber. It’s clear that I need to do more research on Jack’s service history to clarify his exact movements prior to training as an air gunner during 1943.

The crew picture is from the Pearce family collection, and identifies Jack and who we presume to be fellow student aircrew. Jack is centre front. Subsequent information from Peter Coulter from the 550 Squadron website identified them as the ‘Lloyd Crew’ as follows:

Back row L – R: Sgt T.P (Terry) Burke, WO T.A ‘Lofty’ Lloyd, F/O Eddie Yaternick, F/Sgt D.M ‘Steve’ Stephen.

Front L – R: Sgt R.L.G ‘Jumbo’ Moore, Jack, and Sgt Anthony Constantine (Tony) Crilley. This might be the only photo of the crew that exists.

Hemswell was briefly the finishing school from January (having been formed at Lindholme in November 1943) until mid 1944; Jack had joined 550 Squadron at North Killingholme with effect from 27th February ’44, so this picture was taken sometime shortly before then as the fledgling crew were readied for combat.

Hemswell was later made famous for being used for filming ‘The Dambusters’ movie.

This is a link to a video of Lancasters flying out of RAF Hemswell

Returning to the war effort, from the end of the Battle of Britain and the imminent threat of enemy invasion, the allies slowly ramped up their campaign of bombing to counter that of the Luftwaffe. Joined by their USAAF colleagues, the RAF slowly but surely increased it’s capabilities with the formation of many new squadrons, including the Lancasters of 550 Squadron. 550 formed as part of No 1 Group in late November 1943 at RAF Grimsby (Waltham) from ‘C’ Flight 100 Squadron. 100 had been one of the original Royal Flying Corps night bomber squadrons formed back in 1917, so 550 was a natural evolution of their heritage. By January 1944, 550 took up its new home at RAF North Killingholme. The picture below may well contain Jack (I have a suspicion he’s 4th from right on the front row). It would go on to fly 3582 operational sorties, with the loss of 59 aircraft.

550 Squadron, March 1944

The allied air campaign began a war of attrition to demoralise the German war efforts, especially its industrial might; bombing deeper and deeper into Europe. By the spring of 1944 the focus was very much on softening up enemy capabilities in preparation for the planned ‘D-Day’ invasion that would follow in June.

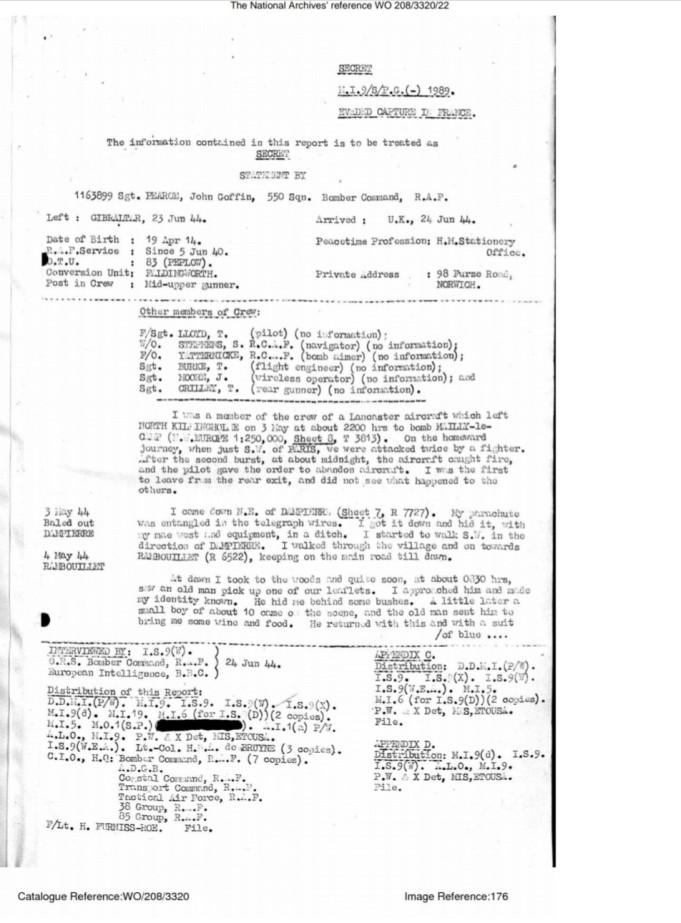

Back, however, to the exploits of Sgt 1163899 Jack Pearce.

On the night of the 3rd/4th May 1944, No.1 & No.5 Groups of Bomber Command attacked in a now famous raid on a Wehrmacht barracks and tank training center close to the village of Mailly Le Camp, to the east of Paris. The night skies of Lincolnshire filled with aircraft and their young crews headed for France. It was a relatively small target and the intention was to destroy it with high explosives. The first wave were the pathfinders of fourteen Mosquito aircraft led by the famous Wing Commander Leonard Cheshire. The pathfinders were accurate in their attack and successfully lit their target. The ‘Main Force Controller’ then coordinated 346 Lancaster bombers to begin the attack, 18 of which were from 550 Squadron, including Lancaster ND733 BQ-J with Jack Pearce onboard. The full crew list for that sortie was: W/O T A Lloyd (Pilot), F/Sgt D M Stephen (Navigator), Sgt R L G Moore (Wireless Operator), Sgt T P Burke (Flight Engineer), Flying Officer E Yaternick (Air Bomber RCAF), Sgt J G Pearce (Mid Upper Air Gunner) and Sgt A C Crilley (Rear Air Gunner).

It was Jack’s 13th operational sortie.

The 550 Squadron aircraft had assembled at their rendezvous altitude at around midnight. As with any large force at the time, it took considerable efforts to converge so many squadrons, and something of a backlog developed in the attack. As a result the Luftwaffe were given sufficient alert to scramble a night fighter response. In total 42 Lancasters were shot down – 258 airmen were killed. Part of the complication came from the Americans using the same operational frequency to broadcast music – hampering the ability of the RAF to coordinate the attack. The reports of the raid give reference to ‘Deep in the heart of Texas’ booming across the airwaves complicating matters greatly!

Despite this, over 1,500 tons of bombs hit their target, destroying over 150 barrack buildings and transport sheds together with over 100 vehicles, including many tanks. Some records state there were “no civilian fatalities” probably based upon a contemporary reports. However other records now tell us there were over 100 French dead, including POWs and forced labourers, along with civilians living nearby.

A Lancaster seen at low level over Mailly Le Camp (Imperial War Museum)

A summary of 550’s part in the raid is reproduced below, with a description of the fate of Jack’s aircraft “J”:

“Eighteen aircraft and crews were offered for operations and were accepted. The crews were briefed to attack the Military Barracks at MAILLY. The accepted number of aircraft and crews took off without incident in the usual Squadron style. The weather was clear throughout the journey to and over the target, good visibility and bright moonlight assisted in locating the target, resulting in the target being effectively dealt with. Fires caused by earlier attacks int he MAILLY area were still burning but the Master of Ceremonies had some difficulties in assessing the markers accuracy, with the result that the main force was held up for some minutes. When the order to bomb was finally given, the rush, to quote W/O Knox “D”, was like the starting gate at the Derby! Markers appeared to be accurate and a very good concentration of bombing at once became apparent with one or two healthy fires and smoke clouds rising to a height of 8,000ft. The flak defences in the MAILLY area were only moderate, although the light flak was more intense than had been seen for some time. Numerous enemy night fighters were present and many combats were seen taking place in the bright moonlight – these combats continued until well on the way homewards. “J” F/Sgt Lloyd had a somewhat “dicey” return journey, about half an hour after having bombed the objective he was attacked by an unidentified aircraft and with the trimming tabs shot away his aircraft became temporarily out of control but managed to shake off the enemy fighter. Five minutes later a second attack set fire to the aircraft bomb bay and fuselage. The order to bail out was given and obeyed by the Mid Upper Gunner Sgt Pearce, Rear Gunner Sgt Crilley and the Air Bomber F/O Yaternick. The aircraft went into a dive which help to extinguish the flame. Sgt Moore the wireless operator, used all the extinguishers to put out the remaining fire, and when these were exhausted, beat out the flames with his feet and hands. Finding the navigator suffering from severe burns, he rendered first aid and took over the navigational duties, obtained accurate fixes which enabled the pilot to bring back his aircraft safely to England, landing at R.A.F. Station FORD. A very good show put up by the worthy members of 550 Squadron. Many crews found that interference from a broadcasting station made listening to the Master of Ceremonies possessive wireless instructions difficult – as F/Sgt Salmon of “Q” said “One didn’t know whether to go in and bomb or stay ‘Deep in the Heart of Texas’!” Fourteen good night photographs taken by the Squadron aircraft show that this small precision target received a good “Strafing”.

One aircraft “H” (F/L Grain and crew) failed to return. In addition to a very fine crew the aircraft contained the Army Local Defence Adviser, who had gone to see what real modern bombing attacks were like.”

Below are Web links to the original documents:

Original Operation Report Here

Sgt Moore’s Report Here

The Parachute Jump and The Escape

So what became of Jack and his compatriots? Despite its damage as described above, Lancaster ND733 BQ-J made it home to RAF Ford in West Sussex. Following orders to bail out over France, Jack and two crewmates did just that. The record shows that Sgt’s Crilley and Yaternick became prisoners of war. W/O Lloyd would immediately receive the Distinguished Flying Medal for getting his aircraft home. The crew were hospitalised. Jack however, would begin an altogether different adventure.

For any airman landing behind enemy lines, surviving a burning aircraft and the subsequent parachute ride through a flak barrage was just the start of a very bad day. At best you would land in one piece and quickly fall into the hands of friendly citizens. At worst, your landing would bring death or injury or the unwelcome attentions of hostile residents or the enemy himself; either of which might take a liberal interpretation of the Geneva Convention. During the course of its history, at least 85 aircrew of 550 Squadron would take to their parachutes. Many would become prisoners, and some would not return. For Jack, the spring morning of May 4th 1944 was thankfully going to end better than it had started.

Luckily, downed airmen had a support network to fall back upon if they could survive their unplanned arrival and locate a friendly face. Coordinated from Wilton near Beaconsfield, MI-9 (Military Intelligence Section 9) had developed a network to liaise with the local resistance in France, who in turn had developed a complex system of escape and evasion routes. So Jack’s first problem after arriving back on Terra Firma was to find that important friendly face. We know Tony Crilley and Eddie Yaternick were captured, but we don’t exactly know how narrow Jack’s escape was. Thankfully, debrief reports and intelligence records survived, and are recorded in the excellent book “They came from Burgundy: A study of the Bourgogne escape line” by Keith Janes (2017) and at the National Archive. A brief mention of Jack also appears in “Legacy of the Lancasters” by Martin W Bowman (2013).

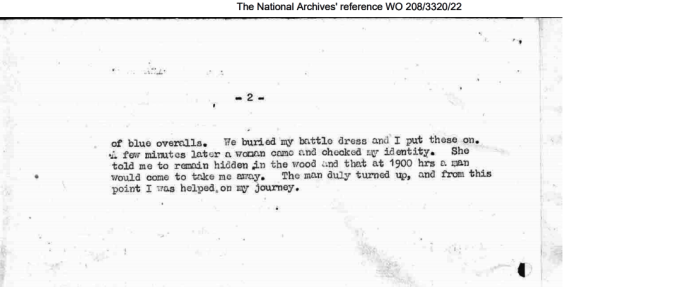

The accounts describe that Jack landed somewhere north east of the village of Dampierre-en-Yvelines, south of Versailles, and was initially caught in some telegraph wires. It seems Jack headed off on foot, following the road south through the village towards Rambouillet when he approached an old man at around 0830, then a small boy arrived. Jack was given food and some wine, and a change of clothes. Hiding in a ditch and burying his kit, a woman helped him hide in some woods until 1900hrs and then a man arrived and instigated his escape journey. I can only imagine the intensity of that moment when Jack placed his liberty and life in the hands of a complete stranger. Jack was taken by horse & cart to Monfort-L’Amaury where he was given a meal at the home of the cart driver and sheltered over night by a neighbour, at great risk to all. The next day Jack was taken by a young man to Rambouillet where he was given lunch by the (unnamed) owner of a local fertiliser business. From there, Jack travelled by train to Paris, then on to Lagny-sur-Marne, east of the city.

Here Jack was introduced to a senior figure in the resistance described as ‘The Chief.’ National Archive intelligence files describe ‘The Chief’ as a man called Octave Boutellier. The record also describes one of the MI-9 ‘helpers’ as Henri Boutellier of 23 Rue du Colonel Durand at Lagny.

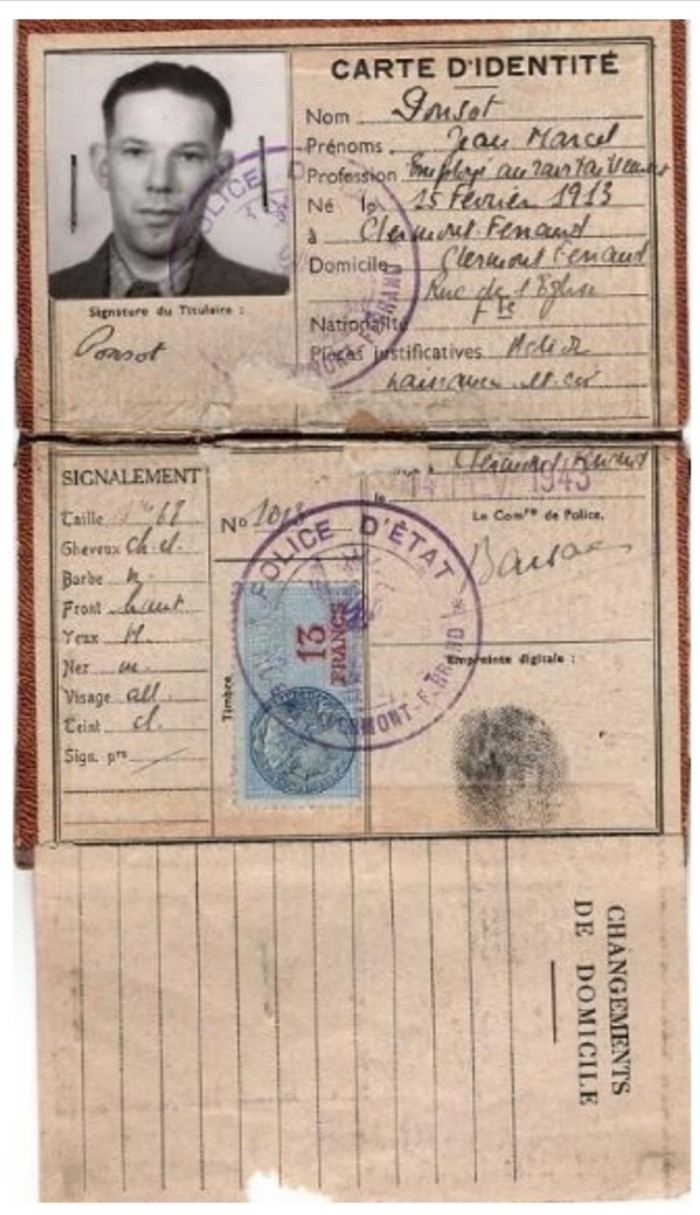

Jack’s false identity papers (Pearce family collection)

These influential agents of the French resistance are most likely the people who organised the false identity papers given to Jack for his journey out of France. Jack would have been interrogated by the French before given any assistance, but we now know Jack was lodged with Henri Herbert Cane at 13 Rue de la Paix at Lagny. Jack was then moved to Dampmart on May 7th where he lodged with Michel Place in his bakery at 7 Rue de Chateau. I have no idea how the resistance chose names for their subterfuge, but I’d like to think ‘Jean Marcel Ponsot’ obtained his fake moniker from the nearest bottle of Domaine Ponsot Burgundy while toasting his new friends!

About a week later, ‘Jean Marcel’ was joined by another airman named Ernest Sparks, and eventually a John ‘Jack’ Pittwood. They would make their journey south together. The networks would gather groups of allied personnel along with other refugees, and slowly disperse them into the chosen escape route. Jack and his group would head south to the Pyrenees and Spain, but individuals would join or leave groups as circumstances dictated.

Crew of ND556 with John Pittwood 2nd from right at the rear (©️ Martin W Bowman)

A brief search (and an entirely different project!) identifies Ernest Sparks, a Squadron Leader of 83 Squadron flying out of RAF Coningsby. Sparks was Gazetted for the Distinguished Flying Cross in August 1944. F/Sgt John ‘Jack’ Pittwood, 20, was aboard Lancaster ND556 EM-F of 207 Squadron flying out of RAF Spilsby. 83 and 207 Squadrons were part of No.5 Group and part of the same raid as Jack. As an aside, 207 Squadron are currently part of the F35B Lightning II program, and will reform as the F35 OCU Squadron just down the road from me at RAF Marham by July 2019.

The Bourgogne Line

There were several named evasion routes – the ‘Comete Line’, the ‘Pat O’Leary Line’ and the ‘Marie Claire Line’ are but three. Over 30,000 escapees were helped over the high passes at night, or by other routes, into Spain. Today you can follow Le Chemin de la Liberte ‘The Freedom Trail’ for yourselves. If you want to know the exact detail of Jack’s journey to Spain, I suggest you buy Keith Janes book, because the detail is too great to reproduce here. Chapter 69 describes ‘The Clonts Group’ – their individual stories, and how they came together for the escape – the book is truly remarkable.

In summary, a group of ten evaders – Jack, F/O Maurice Steel, F/O Bill Alliston, Sqn Ldr Ernest Sparks, F/Sgt Jack Pittwood, Sgt Wilf Greene, Sgt Patrick Evans, Capt Maurice Thomas, 1/Lt Charles Clonts and T/ Sgt Kenneth Nice were rounded up by their helpers and left Paris to head south to Toulouse on May 25th. The book gives great detail of the many movements of the individuals as they were moved from safe house to safe house before the journey. Their guides were Charles and Henri. Given instructions, and told to say they had been sent by ‘Burgundy’ they travelled by the evening train to Toulouse, but because of delays didn’t reach the city until the evening of the 26th. Travel complications caused them to end up in Tarbes – missing their contacts – before lodging near Pau. The book describes the accommodation arrangements for some of the group without specifically mentioning Jack, but by May 30th the group of ten were near Navarennx in the Pyrenean foothills. Handed over to mountain guides, they were joined by a group of sixteen Jewish refugees somewhere near Sainte-Engrace. They set off on this leg to cross the high Pyrenees on foot at 0130 on May 31st, travelling only at night. The group entered Spain around 6am on June 3rd north of Isaba; in total five days on foot in the mountains. From there they headed to Ustarroz where they were picked up by the Spanish authorities and later taken into Isaba. On June 4th they were taken to Pamplona, and after being interrogated and given papers and consular access on June 6th, they would begin their journey home.

As the group ate their breakfast as free men on that Spanish summer morning, D-Day was unfolding on the beachheads of France. At 11.24pm the previous evening, a 550 Squadron Lancaster LL811, bearing the identifier BQ-J (to replace that of the Lloyd Crew) dropped the bombs on Crisbecq, Normandy that signalled the start of Operation Overlord – a beginning of a wider freedom in which they had played a part.

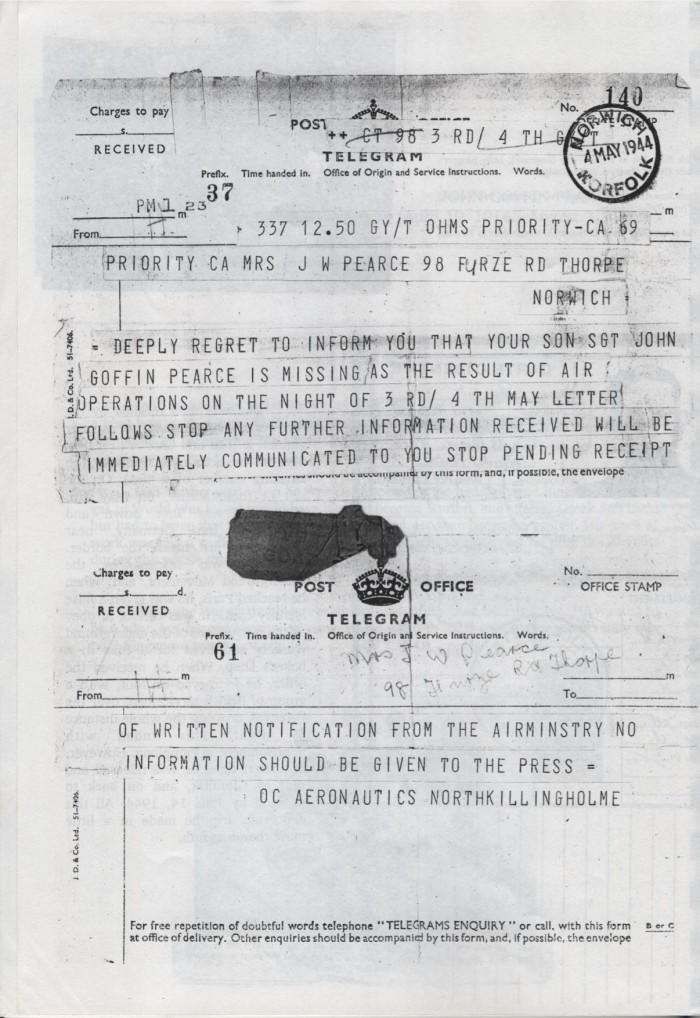

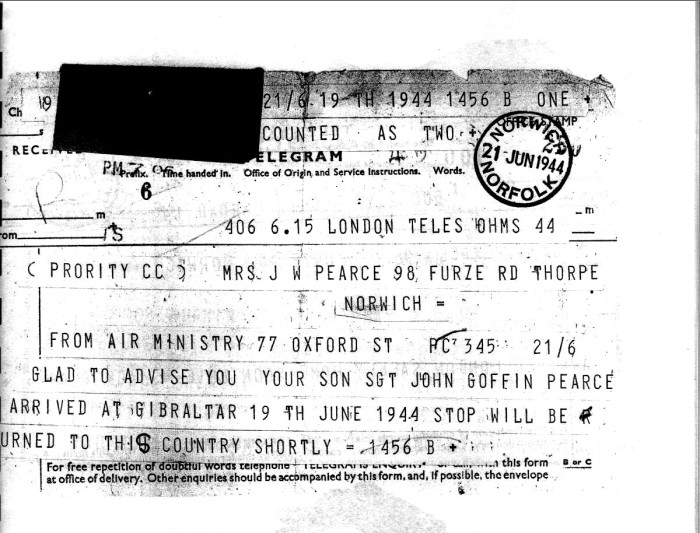

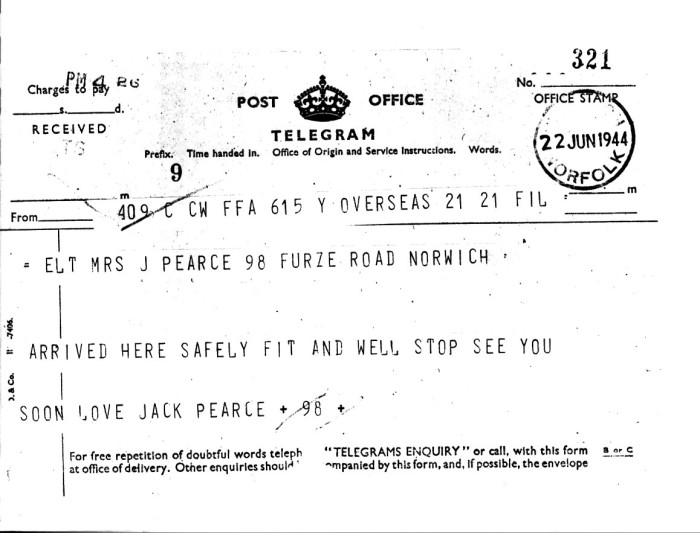

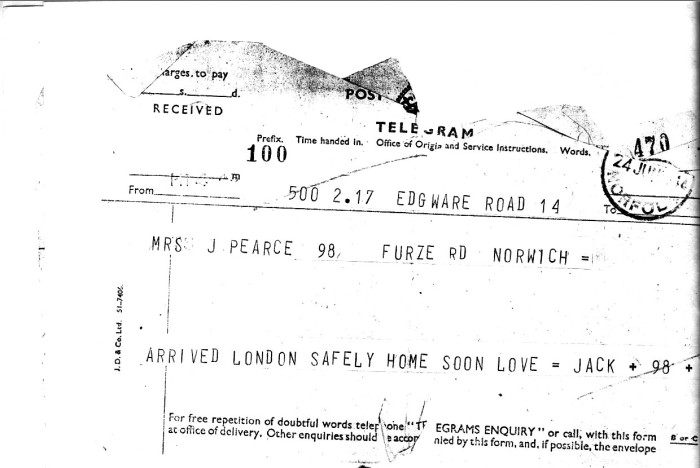

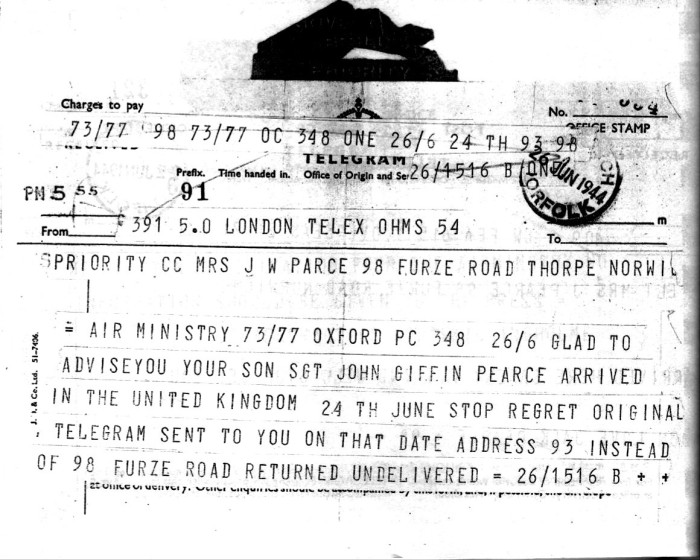

It seems Jack reached Gibraltar on June 19th and was finally flown home to the UK on June 24th. Below are the telegrams revealing Jack’s initial fate, and eventually reporting his safe return.

Jack may have had a second lucky escape, as there are accounts of a following group a day or so later being betrayed by their mountain guides, and a group of Jewish refugees being murdered by a German patrol.

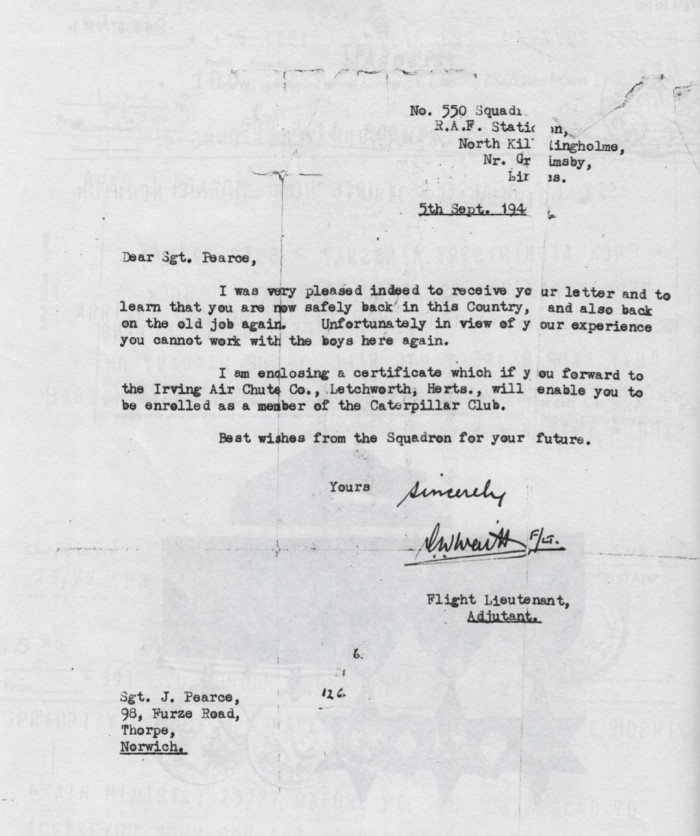

Jack would not return to Bomber Command and Lancasters. Having been behind enemy lines and in the hands of the resistance, an airman would be subject to intelligence debriefing to gain assurances that he was not a security risk. The letter below broke the news that his days with 550 Squadron were over.

Cheerio from 550 Squadron

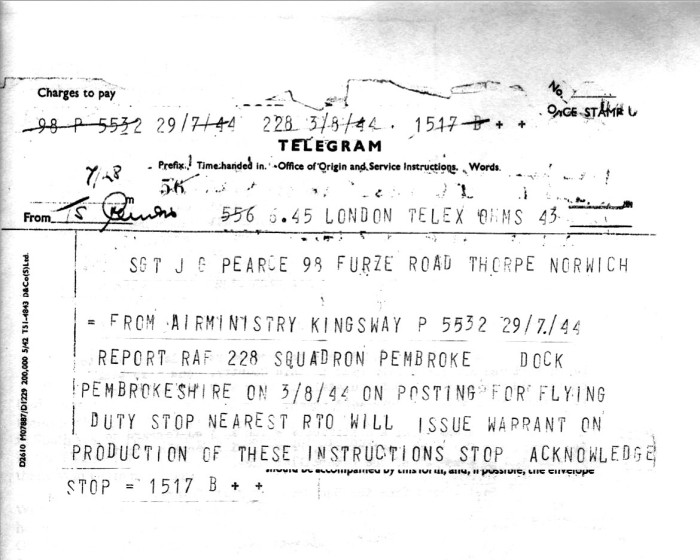

Posting to 228 Squadron August 1944

By the time 550 had said cheerio to him, Jack was already on his next adventure with 228 Squadron Coastal Command crewing Sunderlands at RAF Pembroke Dock in Wales, chasing U boats and E boats in the Atlantic. He would see out the war there, being released in January 1946.

228 Squadron 1945. Jack is 2nd left, back row

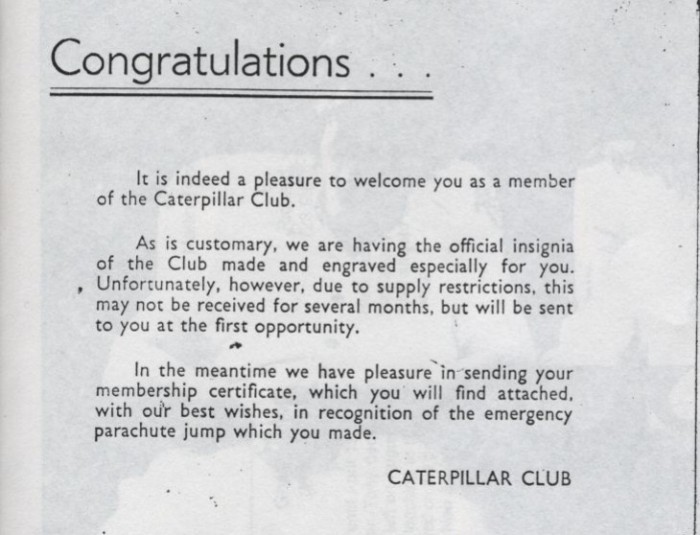

As a consequence of bailing out, Jack also gained membership of The Caterpillar Club.

Issued by the Irvin Parachute Co, membership was fairly exclusive!

Another outcome of his service was the meeting with Ruth May, a Cornish nurse, at Bodmin Emergency Hospital while convalescing, who he would go on to marry in June 1946.

The family history indicates a war service of 90 combat sorties: 13 in Lancasters initially, the rest in Sunderlands – an incredible feat.

Jack and Ruth would return to East Anglia and start a family in Bungay, before moving to Tonbridge in Kent. Jack would go on to a career lecturing at The London College of Printing. From Tonbridge, Jack, Ruth and family would move to Pembury and eventually Tunbridge Wells. In retirement, Jack remained active in support of his church, printing the church magazine among other things. Jack died in August 1992, leaving a legacy of four children, seven grandchildren and nine great grandchildren.

Jack and Ruth, 1986

As for the Lancaster ND733, it too served almost to the end of the war. After the lucky escape of May 1944, it was back on combat duties by October with 463 Squadron Royal Australian Air Force, flying out of RAF Waddington, Lincolnshire. By now bearing the identifier JO-L, it flew on until 16th April 1945 when it was shot down over Juvincourt, France, during its return from a raid to Pilsen, Czechoslovakia, just two weeks before the end of hostilities in Europe. It’s crew, too, bailed out and survived.

ND733 JO-L 463 Sqn RAAF on its final mission April 16th 1945

So there we have the legacy of Jack Pearce. One of many incredible stories, but like so many others, buried in time. Some of the material in this blog now finds itself in the public domain for the first time. For that I am thankful to the Pearce family.

To Jack, and to the memory of the ‘Helpers’ and the 55,573 fallen of Bomber Command

Copyright and reference acknowledgements

Unless stated otherwise, copyright of images, and access to information used in this blog remain the property of 550 Squadron and RAF North Killingholme Association as published in the copyright notice on their marvelous website resource Here

Other images are copyright of the Pearce family or Imperial War Museum where stated or known.

Excellent sources are the following books:

“They Came From Burgundy” by Keith Janes (2017) ISBN 978 1788036 474

“Legacy of the Lancasters” by Martin W Bowman (2013) ISBN 978 1 78303 007 1