Sometimes you have to accept that research is never finished when it comes to family history…..

Family genealogy is such that you often reach the end of a road and have to park your investigation when the sources dry up or the generations pass on, taking the knowledge with them. I’d reached that point with Herbert Crook in 2018 when I wrote about his short life and army service, which ended as a prisoner of war in Mesopotamia.

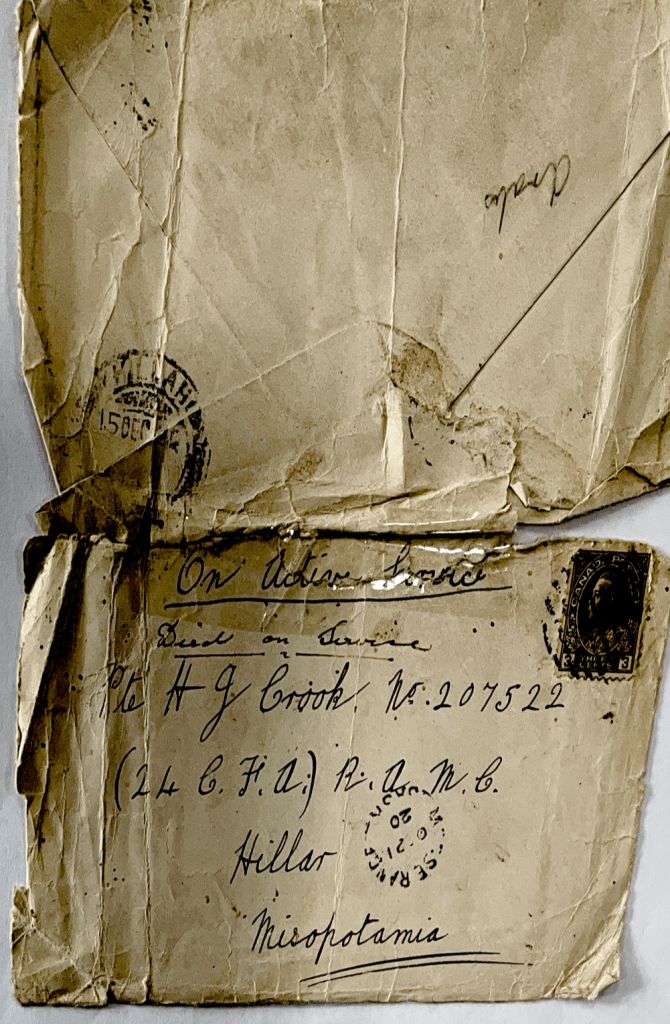

Herbert was one of the lesser known brothers of my grandfather, and the research had proved less straightforward, to the extent that I’d enlisted the help of renowned military researcher Chris Baker to try and tease out the last few facts. Eventually we concluded there wasn’t much else to uncover and agreed that Herbert was most likely serving with the 24th Combined Field Ambulance of the Royal Army Medical Corps at the point he was captured by Arab forces in the summer of 1920. When I began we didn’t even have a picture of Herbert.

You can read the results of our research here:

I’ve recently received a steady drip of new information from cousin Kris in Canada whose grandfather, Fred Crook, was younger brother to Herbert. It was Kris who had turned up the picture of Herbert that had proved so elusive, but it was something of a surprise when Kris sent me another letter…

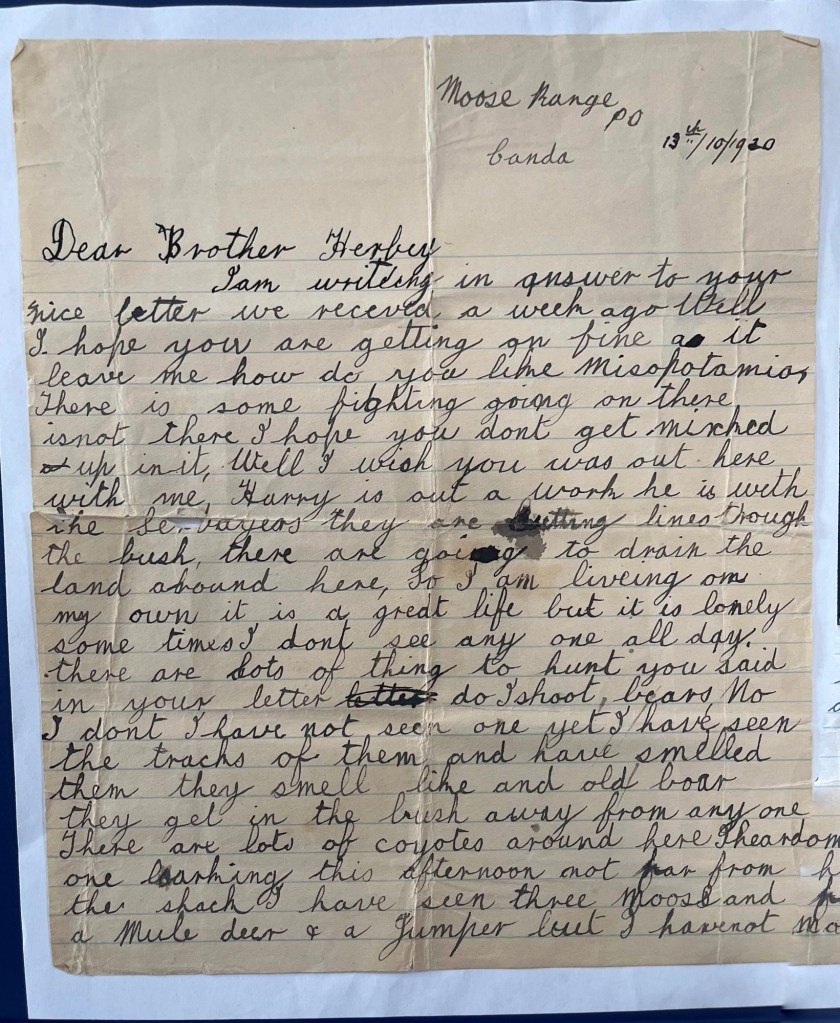

The letter is unremarkable in that it’s written from one brother to another on opposite sides of the world, with Fred describing life in the Canadian bush with brother Harry, and their efforts to forge a living.

I’m pleased to say that it validated my research by confirming that Herbert was indeed attached to 24 CFA at Hillah, so it is a nice footnote to his story.

Sadly though, it’s another poignant reminder of how slowly the world turned a century ago.

When Fred put pen to paper on 13th October 1920 in reply to a letter from his brother received a week earlier, and posted his letter at Moose Range, Saskatchewan, he was unaware that Herbert had already been declared dead almost two months earlier. Such was the delay in international postage and the remoteness of their respective locations, it seems likely that it would take two months for correspondence to travel halfway round the world.

It seems that the letter arrived in Mesopotamia in the December of that year, by which time Herbert was long gone. Sadly we don’t know how long it took for the news to reach family in England, but we assume it wouldn’t have been much faster.

You’ll see from the connected blog about Herbert that he might be unique in history as the only prisoner of war to die in captivity as a result of that conflict. He certainly wasn’t unique in that so many sons were cast across the globe and suffered a similar fate. What we don’t have is the reaction of Fred to the news that another brother had been taken by war.

Either way, this might be the final chapter.

Unless of course, Kris unearths another letter from beyond family memory….