Eighty years have now passed since the first celebration of Victory in Europe, bringing into sharp focus the dwindling numbers of servicemen and women who survive today to remind us, first hand, of the achievements of our greatest generation. Fewer still is the number remaining who saw service in the face of the enemy.

As I write this, the bunting and flags of our #VEDay80 commemorations have been packed away and are already a month behind us, and this week has seen the 81st remembrance of the Normandy landings; a much quieter affair than the decennial fanfare of 2024.

Memory has been parked again as we gradually, but inevitably, reach the point that they that grow old are no more, and we close the book on another chapter.

I speak up now, because of all the men of my family of which I have knowledge, and who served, the final piece belongs to uncle Bert; who exists in family records as a couple of blurry photographs and has faded from memory.

Bertram Cole was a younger brother of my grandfather, and he deserves a mention now to remind us, that as we tick off these anniversaries in history, the war had not ended on May 8th 1945. For so many like Bert, war lingered on long after the streets and public houses of home had been cleared of the victory parades and parties.

I remember uncle Bert from my childhood, mainly from the times that I would be taken to watch Norwich City when Dad and I would be joined in the South Stand by a gathering of uncles and cousins along with my grandfather. There was also the serious business of bowls – uncle Bert and my grandparents were all heavily involved with East Harling bowls club, and occasionally us kids would be tolerated at the hallowed turf when they played.

My grandfather died in 1974, and after that the family gatherings at football dwindled as I, and they, grew older. I have very fond memories of a dozen or more of us all together at the football.

Having said all of that, I can’t say that I knew uncle Bert well; as is always the case, most of what I know about him has been handed down via Dad, and we are all left wishing we asked more questions when we were kids, although in the case of Bert, perhaps answers would have been much less likely to be forthcoming for reasons that are now all too apparent.

So I want to put some of the history straight, and to tell his story, such that it is, so that he is not forgotten. So that they are not forgotten.

Military Service

I have not obtained Berts service file (they’re currently in the process of being digitised for public release and applications take up to a year) but we have enough facts to tell his story.

Bert was born at East Harling on 30th April 1921, and makes his debut in the public record at 1 month old in the census of that year. His date of birth is a feature of interest later in his story.

I can’t find him in the 1939 Register of September of that year, but we know that by then, aged 18, he had been mobilised with the Royal Norfolk Regiment. He had been a labourer prior to that.

But what we also know is that Bert had already enlisted as a Territorial soldier well before the outbreak of war.

There are a number of papers we can draw on, but it seems that Bert joined up with the Royal Norfolk Regiment on April 12th 1936. The remarkable point about that date, if it is to be believed, is that it means Bert was 18 days shy of his 15th birthday!

I’m not an expert on interwar recruitment policy, and I can imagine that ‘boy soldiers’ were a long established legacy of the British army, so I’m unsure what to believe; but I do know that the question of underage recruitment was discussed in parliament at that time, which I reproduce below from Hansard.

As can be seen from the debate, Sir Victor Warrender seems to accept that the army was happy not to ask too many difficult questions as long as a recruit looked mature enough. It is how they had always operated and how so many children served in the trenches of the Great War. We will see later how Bert was recorded during his service.

So what of Bert’s war?

I know nothing specific, but I can give an outline of what became of him through the movements of his regiment. His war service was with the 4th Battalion. We don’t have a picture of him in uniform, and I’ve been unable to pick him out in several shots of the various companies of the 4th Battalion that exist.

The Battalion was embodied on 3rd September 1939 with Battalion HQ and HQ Company at Chapelfield Drill Hall, Norwich, A and D Companies at Great Yarmouth, B Company with detachments at Wymondham, Attleborough, Thetford and Watton, C Company with detachments at Diss, Harleston and Long Stratton. I don’t know to which company Bert belonged, but I suspect it was B.

Their Commanding Officer was Lt Col J H Jewson MC TD. Second in command was Major A E Knights MC MM TD, Adjutant was Major S J Pope and Quarter Master Captain W F Chapman.

The strength of the 4th Battalion was 29 officers, 39 Warrant Officers and Sergeants and 607 other ranks, making a total of 675 men.

In September 1939, four sergeants and 91 other ranks were transferred to the 6th Battalion, leaving the 4th with 580 men in total. The 4th and 5th Battalions were brigaded together and with the Suffolk Regiment formed the 54 Infantry Brigade under Brigadier E.H.W.Backhouse as part of the 18th Division.

In October the Battalion was at Gorleston, the H.Q located at the Holiday Camp situated at Bridge Road with “A” and “B” companies.

“D” Company were at York Road Drill Hall, and “C” Company was at Great Yarmouth Race Course. N.C.O´s and other ranks were drafted from the 2nd Battalion to commence intensive training.

In May 1940 the 4th Battalion were given coastal defence duties as invasion seemed imminent with the retreat from Dunkirk ongoing. 54 Infantry Brigade had the job of defending the beach from Cromer to Lowestoft, with the 4th Battalion covering Gorleston and Yarmouth, as an echo of Bert’s grandfather George Burlingham covering Lowestoft with the 2/4th Norfolks in 1915.

In June 1940 the Battalion increased to 29 officers and 950 other ranks by drafts from the I.T.C., Royal Norfolk Regiment, at Billericay and the I.T.C., Wiltshire Regiment. On August 23rd 1940 the King visited Battalion H.Q. and inspected the Officers and men at Gorleston Holiday Camp.

On September 18th the battalion was moved to Langley Park, Loddon and were almost immediately put into Action Stations as an invasion was thought to be under way. The alert lasted half a day.

54 Brigade were eventually moved to Cambridge for more intensive training and were replaced by Home Defence units at the coast. They believed they were being readied for service in North Africa.

In December 1940 it received mobilisation orders and to carry out Brigade and Divisional training. It moved in early January 1941 to Scotland where it remained until April when it then moved to Blackburn. In July it moved to Ross-on-Wye in Herefordshire. In October, His Majesty George VI again inspected the Battalion and Lt Col J H Jewson MC TD relinquished the command he had held since February 1939 on being promoted. He was succeeded by Lt Col A E Knights MC MM TD with Major J N Packard as Second in Command.

The Battalion sailed from Liverpool on 29th October 1941 aboard RMS Andes and joined a convoy just north of the Clyde. An American squadron, including a battleship and the aircraft carrier Lexington took over as escort. The convoy then headed west towards Halifax, Nova Scotia. Mid Atlantic, the men were transhipped to the troopship USS Wakefield.

On November 10th the voyage continued with six American troopships, two cruisers, eight destroyers and the aircraft carrier Ranger made up Convoy ‘William Sail 12X’, their destination still unknown.

After a month of sailing across the Atlantic and Carribbean, the convoy arrived at Cape Town, South Africa.

America had officially entered the war as the Japanese had bombed Pearl Harbour and attacked Malaya while Bert was at sea; rumours began to spread that they were heading for the Far East and not Egypt as first thought.

On December 13th the convoy left Cape Town and sailed along the coast of East Africa past Madagascar and into the Indian Ocean heading for Bombay. After 17,011 miles at sea Bombay was reached on December 27th 1941. From there it was onward to Malaya.

Disembarking at Keppel Harbour, Singapore, on the 29th January 1942, the 4th Royal Norfolks marched on to the Ketong area.

They immediately found themselves under Japanese aerial bombardment and the USS Wakefield was hit causing several casualties. Once organised, albeit short of supplies, they linked up with the 5th & 6th Battalions who had arrived ahead of them and had already been engaged with the Japanese for a fortnight. The 18th Division was moved to hold the north-eastern part of the island near the Changi Peninsula.

So where and how did Bert’s war reach its climax?

The Battle of Bukit Timah

On the night of 10 February, two divisions of the Imperial Japanese Army attacked Bukit Timah, a strategic high point, capturing the area in the early hours of 11 February.

A subsequent British counterattack to retake Bukit Timah proved unsuccessful, leaving the Imperial Japanese Army in control over the strategic Bukit Timah area. On 12 February, with the Japanese only 5 miles from the city centre, Lieutenant-General Arthur Percival ordered a general retreat into the final defensive perimeter around Singapore City.

To recapture Bukit Timah Village, a hastily assembled unit known as ‘Tomforce’ counterattacked at dawn. Tomforce was commanded by Lieutenant Colonel L. C. Thomas and comprised three battalions drawn from the 18th Division – namely the 4th Royal Norfolks, 1/5 Sherwood Foresters, 18th Reconnaissance Battalion and one battery of the 85th Anti-Tank Regiment. To support Tomforce, Maxwell’s 27th Brigade was ordered to attack towards Bukit Panjang, hoping to catch the Japanese in a pincer movement. However, Maxwell’s attack never materialised because of poor coordination, and the 27th Brigade’s attack order was rescinded before noon.

At around 6.30 am, Tomforce began their attack but was stalled at the Bukit Timah Railway embankment in the face of heavy Japanese resistance. On the attack’s left flank, the Foresters managed to advance within about 400 metres of Bukit Timah Village, but were driven off by the Japanese at around 10.30 am. Tomforce also came under Japanese air attack, including a flight of Japanese medium bombers that were diverted from targets in Keppel Harbour and Singapore City to disrupt the counterattack.

Tomforce’s attempt at Bukit Timah proved to be the only serious counterattack carried out by British forces during the Battle of Singapore. With the bulk of Percival’s forces kept on the eastern side of the island, the counterattack did not stand a good chance of success. By the late afternoon, the counterattack was called off, and Tomforce retreated towards the Chinese High School.

The loss of Bukit Timah was disastrous to the British defence of Singapore, as the remaining depots under British control only had 14 days’ worth of food and very little petrol. Because of these shortages, Percival ordered that no further supplies were to be destroyed without permission.

With the Japanese holding Bukit Timah, the British were now unable to defend the two reservoirs.

Percival was forced to cede Pierce Reservoir and the north bank of MacRitchie Reservoir, relying on control of the MacRitchie Reservoir’s southeastern bank and Woodleigh pumping station to ensure the city’s water supply. Defending the reservoir and pump station was Massy Force, a mixed unit that comprised the 1st Cambridgeshire Regiment, 4th Suffolk Regiment, 5/11th Sikh Regiment and remnants of Tomforce. The Massy Force commander, Brigadier Massy Beresford, assumed responsibility for the front from Thomson Road to Bukit Timah Road.

While the Japanese eventually captured MacRitchie Reservoir on 13 February, they did not prevent the reservoir’s water from flowing through the pumping station. However, heavy damage to the water pipes sustained from Japanese shelling of the city caused the loss of more than half the water supply. The Woodleigh pumping station would remain operational on 15 February, the day of the British surrender.

On the morning of 12 February, Japanese tanks attacked along Bukit Timah Road towards The Chinese High School. While the Japanese attack was stopped by Massy Force around the Adam Road–Farrer Road Stop Line, this placed the Japanese within just 5 miles from Orchard Road and the city centre.

Faced with an imminent Japanese breakthrough into Singapore City, Percival decided to form a 28 mile closed perimeter surrounding the city. British and Indian troops deployed in the north and east of Singapore were withdrawn into this defensive perimeter, which encompassed Kallang Aerodrome, Woodleigh pumping station, Adam Road, Farrer Road, Tanglin Halt, The Gap and Buona Vista Village.

At around 8.30 pm on 12 February, Percival ordered the demolition of the Changi defences – including the massive 15 inch coastal guns of the Johor Battery, to prevent them from falling into Japanese hands. For the past three days, the British coastal gunners of the Connaught and Johor Battery had fired at Japanese targets in Johore, Tengah and Bukit Timah Village.

This final withdrawal ordered by Percival on 12 February 1942 set the stage for the last, desperate battles at Pasir Panjang Ridge between 13 and 14 February 1942.

Capture And Detention

On February 15th 1942 a white flag and the Union Jack were driven down the Bukit Timah Road and the capitulation of Singapore was complete.

The surrender of Allied forces is one of the most contentious decisions of the war – many veterans would tell you they regret being unable to fight to the end, albeit the outcome was likely inevitable such was the force of the Japanese attack.

I have Bert’s Bren gun instruction manual, so I suspect he would have been a gunner on a Bren carrier deployed with Tomforce in the counterattack at Bukit Timah. I do know that he felt they could have fought on for longer, such was his pride.

Bert and his comrades were marched off to the nearby infamous Changi prison camp where their humiliation and long detention would begin. The Japanese code of Bushido did not recognise surrender and the allied prisoners were treated with contempt as they were stripped of possessions and slowly formed into labour parties. I don’t know how long Bert was held at Changi before being moved, but in any case, conditions were extremely tough and completely alien to men from Norfolk.

Bert would be sent, like so many others, to construct the Burma railway as the Imperial Japanese Army sought to expand its military infrastructure across the inhospitable jungles of south east Asia.

This entailed a long journey north by cattle truck over several days and nights to what is now Thailand, in insanitary conditions. The brutality of the regime under which they found themselves bears no description where death as a punishment was as equally present as fatal disease and death from hunger and exhaustion.

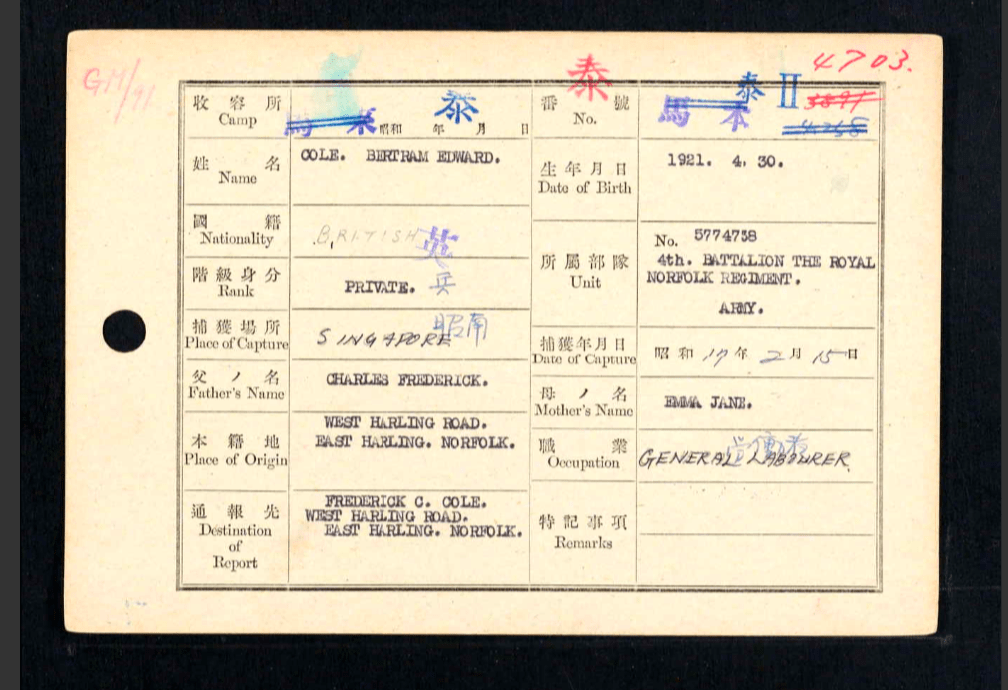

The Japanese army was fanatical in its records as it was in its military objectives, and for that reason Bert is recorded in a number of files, all of which can be accessed via the CoFEPOW website.

The Railway Of Hell

After capture at Singapore and detention at Changi, he was held in camps at places like Tha Khanun, Chungkai, Tamuan, Malai and Kwai (Kanchanaburi) – all camps on the infamous Burma Railway built by prisoners of war and slave labour.

I don’t intend to retell the story of the death railway here as it is well documented elsewhere, but at least we have some record of where Bert was sent after Changi. The camps are listed in kilometres from south to north as the railway was pushed out across modern Thailand, with an equal effort pushing in the opposite direction from the north until both sections met in late 1943. Bert appears in various databases, such as below, compiled from the Japanese files or at the end of the war, but not all identified which camp in which he was held, or when.

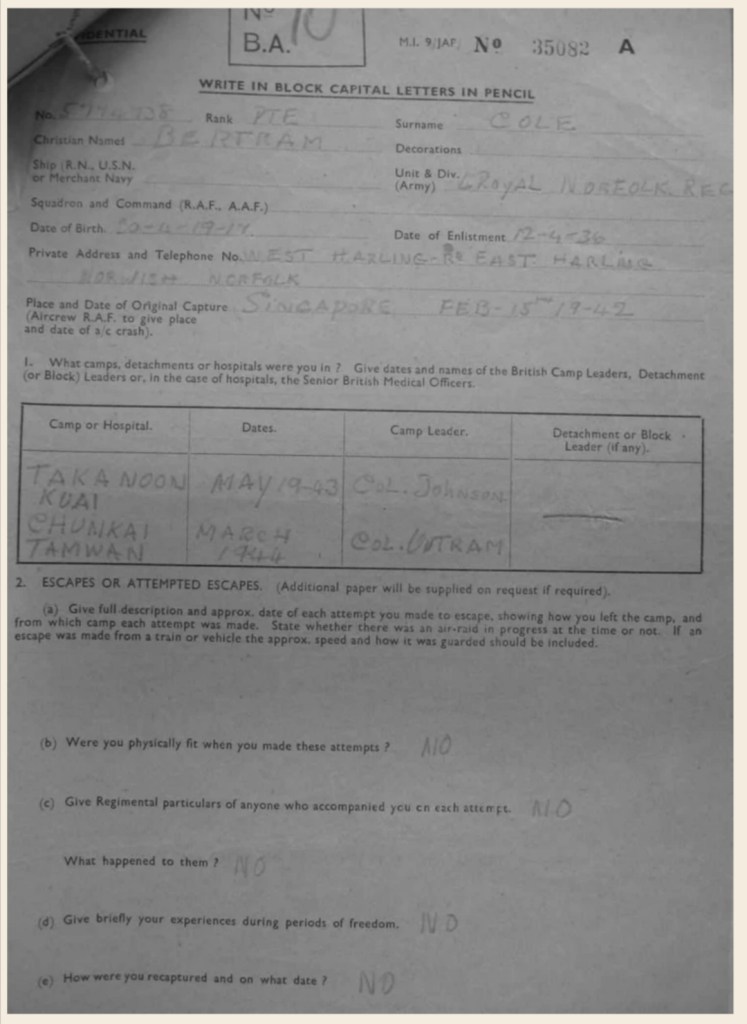

We also know more about Bert’s movements because on release from captivity, Bert was required to complete a liberation questionnaire outlining his detention.

The most interesting fact from the questionnaire is the date of birth given by Bert of 30th April 1917, which as mentioned earlier, might give more context to his story.

Did Bert lie about his age on enlistment on April 12th 1936? Was he not quite 15? Did he live the lie throughout his entire service and continue it when questioned on his release?

It is notable that he gave his correct date of birth to the Japanese seen in their census document above. Maybe he didn’t expect to survive captivity and felt he could tell the truth? We will never know as it’s too late to ask him now, and he never told his story.

Some details of the camps in which Bert was held are below, and gives us some idea of his detention during his time on the railway, but we don’t have precise dates for his journey along the construction route.

Tamuang, (Tha Muang) Camp 39k

Tamuang POW Camp, thirty nine kilometres north of Nong Pladuk, or eleven kilometres south of Kanchanaburi, 375 kilometres south of Thanbyuzayat.This newly built camp, in Tamuang became base camp for POWs when the Railway was completed. By March 1944 the majority of POWs were brought out of the jungle work camps and so-called hospital camps (they had minimal if any medical equipment or supplies) and were concentrated in the main camps at Nacompaton, Non Pladuk, Tamuang, Kanchanaburi, Tamarkan and Chungkai.

Kanchanaburi (Kanburi, Camp 4) 50k

Kanchanaburi was the Japanese Headquarters for the construction of the southern part of the railway in Thailand and the most important base station for them. In the area of Kanchanaburi was a large locomotive shed station and as well as the POW camps and hospital. The whole area was one big storehouse. The railway head offices were located near 49.00 km. These included the train control for all the moves north to the border. At Kanchanaburi there was a Base Hospital Camp, Working Camp and Aerodrome Camps No. 1 and No. 2. Later ‘F’ and ‘H’ Hospital Camp was constructed. Men were brought back to these camps on stretchers off river barges or the railway. They suffered from diseases such as dysentery, malnutrition, beri beri, ulcers, pellagra and all of them had malaria.

Chungkai Camp & Hospital Camp 60k

This camp was about 6 kilometres from Tamarkan. From Tamarkan, the railway line veers left over a river crossing to the next camp location, Chungkai. Chungkai was HQ for Group 2 (made up of about 11,000 POWs) and their work included the two bridges across the River Kwai, one of which was constructed of wood and the other which commenced at the same time, constructed of steel and better known as “The Bridge over the River Kwai” of fictional movie fame. This was often an arrival point for men joining the railway labour system.

Malai (Malaya Hamlet, Konyu) 151km

Malai or Malaya Hamlet was occupied from 21 May 1943 by the Australian and British POWs of H Force with the Australians under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel R.F. Oakes. Situated near the notorious Hellfire Pass like many camps along the railway, it was surrounded by dense bamboo and conditions were primitive. The POWs arrived exhausted after a long march to find no accommodation, latrines or cookhouses. There was at least a small stream but the water had to be boiled before drinking.

Takanoon (Tha Khanum, Takunun), 222km

This was also a staging camp for columns heading north. Known as ‘Whale Meat Camp’ it was described as being the best jungle camp at the time. One of several camps in that location and much further north.

After The War

Bert was liberated on September 5th 1945, four long months after the entire nation partied in the streets at home.

The war in Europe was won, and the public attitude to war had changed after five long years of sacrifice, as demonstrated by the resounding defeat of Winston Churchill in the election of that summer. While the war dragged on in Asia, Britons at home were keen to put it behind them and wanted a return to normality. Men like Bert were out of sight and out of mind for everyone but their loved ones.

After a long journey back to England, Bert was discharged from the army on March 25th 1946, almost a decade to the day that he signed up as a boy.

We can only imagine the ghosts that lived in his mind from his experiences when he returned home.

That he never, to my knowledge, ever spoke about his experiences is understandable, but a long held refusal to entertain anything Japanese in his life was a common theme. There is also a legendary tale of a confrontation with a group of Japanese businessmen at Shadwell Stud, which is a tale not for retelling here.

All I have is a memory of a quiet man who chose to keep his memories to himself.

Bert married Evelyn Harvey in 1946, and settled into married life at Rushford.

The slightly blurred photograph of their wedding day looks a happy scene, and I hope that by then he had begun to repair himself. Their son Rodney came along in 1948.

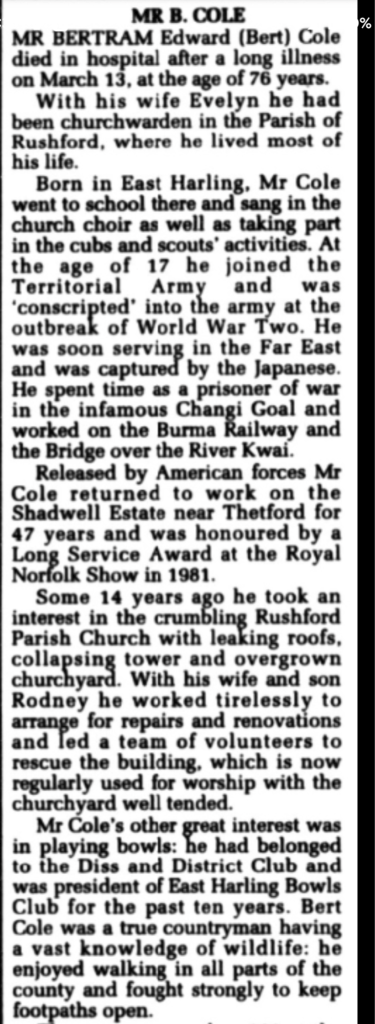

Bert went on to work for the rest of his life for Lord and Lady Musker on Shadwell Estate, and the summary of the following years are best described by the obituary published in the Diss Express after his death in March 1998.

More than 12,500 allied prisoners of war died in the construction of the death railway, along with an estimated 80-100,000 Asian civilians used as forced labour. The 4th Battalion lost 124 men; many more returned home all but broken by starvation or disease.

In this respect, Bert was one of the ‘lucky’ ones.

Perhaps I’ve dumbed down or underplayed the sheer cruelty and horrors of what happened to the men who fell into Japanese hands; I’d rather make sure that Bert was remembered for who he was than what was done to him or his comrades. Remember their strength and fortitude; remember their fierce pride as survivors. But most of all, remember – for they are probably all now gone.

Remember the sacrifices of those who were taken prisoner in Malaya, and those who fought the Japanese to the bitter end in Burma, because they are not forgotten.

This year, the national VJ80 Commemoration will be held at Norwich Cathedral on August 15th to mark the memory of those who fought in the war in the far east. Memories will also hopefully be shared at war memorials on quiet village greens and in town squares across the nation.

Sadly, I have been unable to confirm how many Burma Star/Pacific Star veterans are left. I suspect it may be less than a handful, if any. The Burma Star Association laid up its Standard in 2020. Bert held the Pacific Star, 1939-45 Star and War Medal for his troubles

For this reason, we should make an extra effort to remember the men of East Anglia who travelled halfway round the world to fight a forgotten war, before time finally closes the book on so many men like uncle Bert. It is the very least we can do. There is little point in any of us being angry on their behalf so long after what they endured. Their suffering, and our thanks, are eternal

‘When You Go Home, Tell Them Of Us And Say,

For Your Tomorrow, We Gave Our Today.’

For anyone interested in the stories about the men of the Far East prison camps, please visit https://www.cofepow.org.uk/