27 Dec 1918-14 Dec 1998

Of the many blogs that I’ve written, the overwhelming majority have been about my immediate family tree, or that of my wife. Grandfathers, Great-Grandfathers Great Uncles; so many stories from corners of the family history near and far. When I set out upon my mission to document the fighting men of the family, I hadn’t planned to cover so many varied anecdotes, but through the years I’ve branched out to cover the womenfolk of the family affected by war, and occasionally also blogged about the ancestors of friends.

I’ve covered prisoners of war before too, in the stories of Herbert Crook and Stanislaw Brzeski. I also shared in great detail the story of Jack Pearce, who would have himself become a prisoner of war had it not been for the bravery and commitment of the French Resistance movement when he was forced to abandon his aircraft over French soil in May 1944. Jack was also the son of John William Pearce, who featured in my most recent blog; John is great grandfather to my wife.

Such is the beauty of family history that it often provides quirks of fate. One such quirk is that after the war Jack raised a family, and one of his sons went on to marry a French girl, Muriele. It turns out that, like me, Muriele is obsessed with family history and has been on a long journey of discovery in both the Pearce family tree and that of her own French ancestry. We regularly share notes and research, and it was perhaps no great surprise when she shared with me a piece she had written about her great uncle and his experience in World War Two. Other than the perspective of Stan Brzeski, it’s the first time I’ve been able to study the subject of the war from the standpoint of another of our Allies.

When someone gifts a story so well written and researched, it seems a shame not to share it. Muriele has given me permission to share that story here.

I leave you with the words of Muriele. All family photos remain in the copyright of her family.

Yves Clément Marie was the youngest child of the 6 surviving children of Charles Edmond Marie and Marie Camille Angèle Thiriat, who incidentally, became Marie Marie upon her marriage. My great-grandmother was actually known by her third forename probably to differentiate her from her sister who was also named Marie (Marie Clémence).

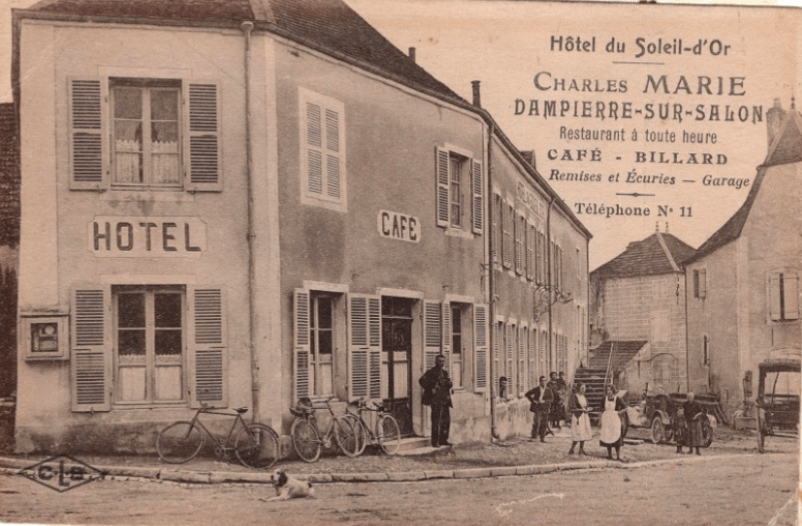

Yves was born on 27th December 1918 at Jeuxey, in the Vosges in Northeastern France. His parents, Angèle and Charles ran a café/hotel in Dampierre-sur-Salon, Bourgogne, called “L’ Hôtel du Soleil-d’Or” (The Golden Sun hotel).

They later moved to Bondy, a northeastern suburb of Paris, where they ran a grocery store. They had a house near Fréteval, a village located on the right bank of the river Loir, where my mother, Liliane Rouge, spent her summer vacations during the Second World War.

According to some family sources, Yves and Hélène were engaged before the Second World War. Hélène was Germaine Camus’s daughter. Germaine married Raymond Marie, Yves’s eldest brother. Hélène was born out of wedlock but Raymond acknowledged her as his own. It is fair to say that Yves and Hélène were not blood relatives. However, malicious rumours were spread about her dealings with the Germans and Yves broke off the engagement. I have been told that Hélène, who was a very pretty girl was usually sent shopping because she was popular with the German soldiers, so it made life easier for everyone. Some members of the family took umbrage to this, and hinted that she was a collaborator, and spread malicious rumours but I have been told that there was nothing untoward.

Yves married Marie-Louise Poulain, with whom he had corresponded during the war, on 20th October 1945.

So, a long happy but ‘ordinary’ life until I received an e-mail from Filae, the French genealogy website, informing me that Yves appeared on the list of French prisoners in Germany. Using whatever information I could glean from the internet I tried to piece together what his life might have been like during my great-uncle’s detention and then, contacted my cousin, his son: “Did you know your father had been a prisoner of war?”. “Yes”, he replied, “but he never talked about it”. He must have contacted his sisters because, suddenly, records kept in forgotten drawers appeared. He also got in touch with a person who confirmed when he was taken prisoner.

So, from the scattered information, here is my account of Yves’s experience of the Second World War :

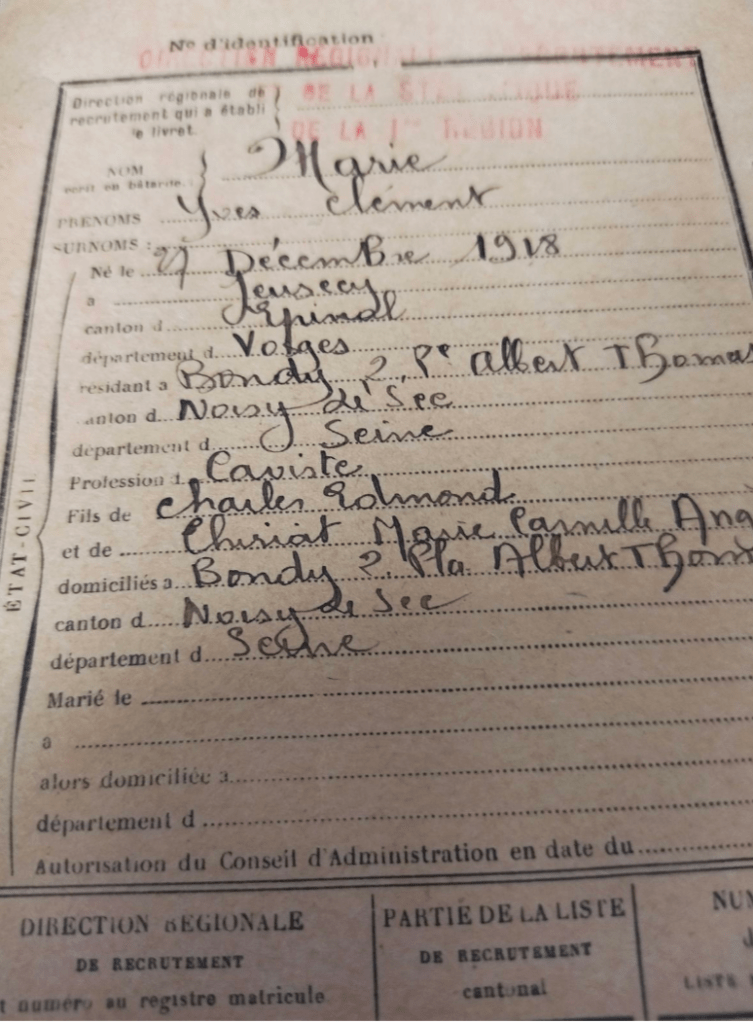

Yves was recruited at the start of the Second World War as evidenced by the document below.

His profession is recorded as “Wine merchant”.

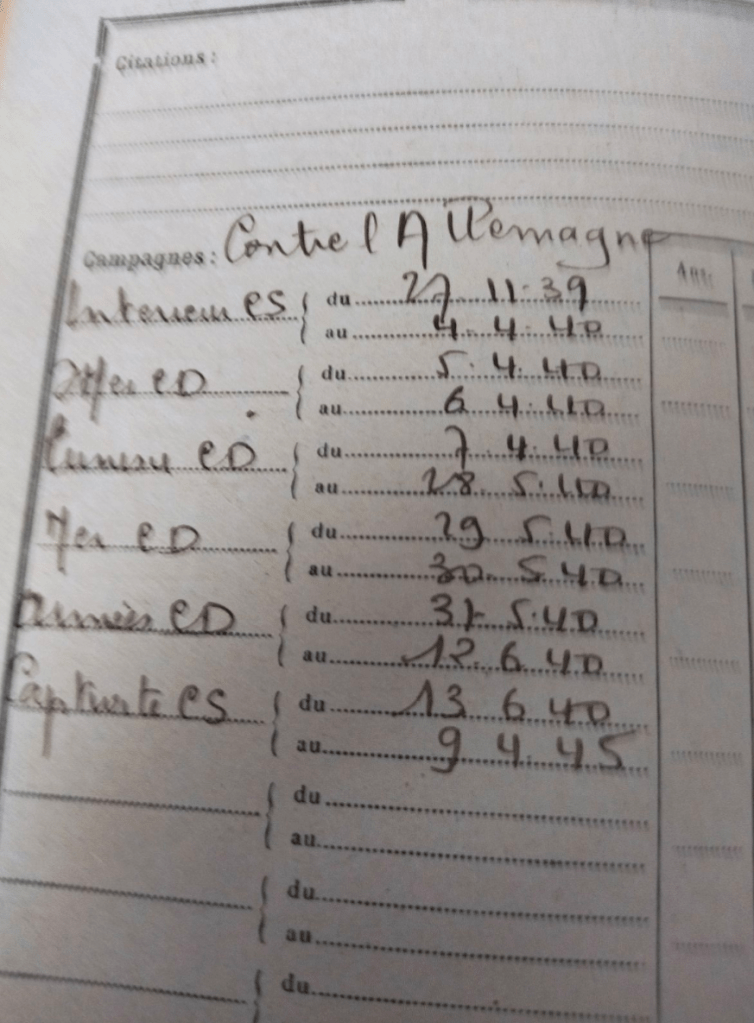

The two following documents detail Yves’ military path. Yves was recruited on November 15, 1939. He embarked for Marseille on April 5, 1940 and disembarked in Tunis on April 6. He embarked in Bizerte on May 29 to return to Marseille on May 30.

He was taken prisoner on June 13 at Isle Adam in Val d’Oise and interned at Stalag VI D under the number 10645.

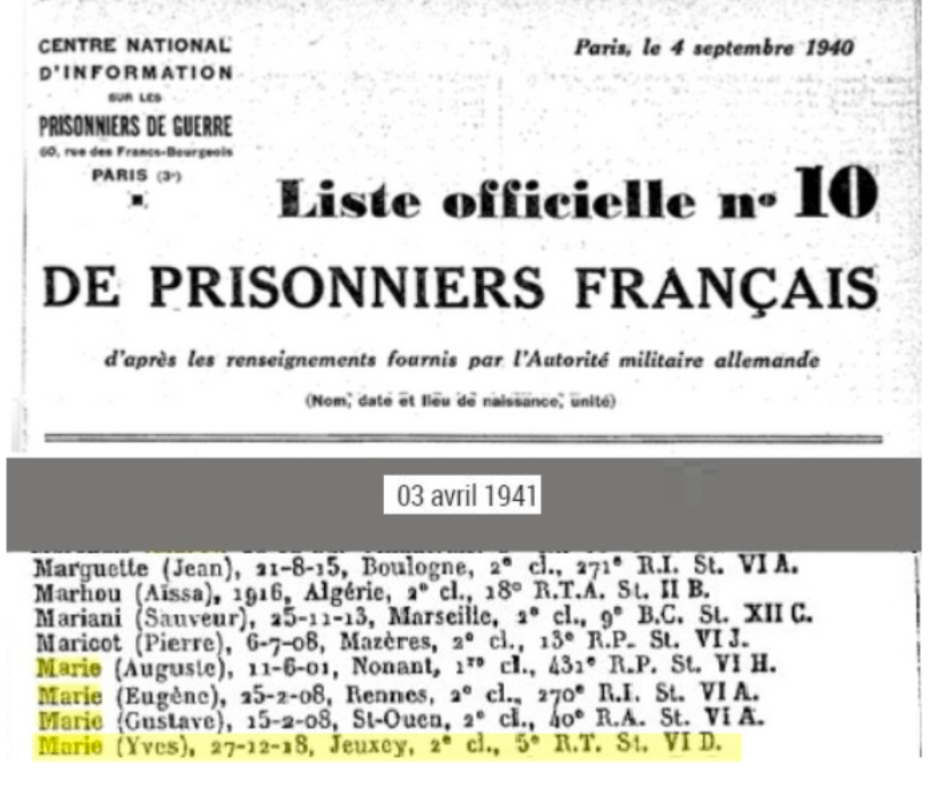

Extract from the meldung (German list/report) on which Yves appears. This is No. 103 of the VI D, this is his registration number:

The list of French prisoners confirms the presence of Yves at Stalag VI D (Family name followed by forename, date and place of birth, rank, unit and location):

French Prisoners of War World War II

French prisoners of war from the Second World War, numbering 1,845,000, captured by the armies of the Third Reich after the armistice linked to the Battle of France during the summer of 1940, were initially housed in camps set up in France in the occupied zone, called Frontstalags, and were then sent on foot or by train to camps in Germany, namely the Oflags which welcomed the officers and the Stalags which welcomed the soldiers and non-commissioned officers.

About a third of French prisoners were released under various conditions (some for medical reasons).

Some prisoners remained in Germany, but nominally became civilian workers. They then stayed in specific camps, called worker camps.

They worked for the Germans, notably the Todt organization or for French companies participating in the Occupying war effort. They were paid 10 francs per day for 6 to 8 hours of work, when a labourer at the same time was paid 10 francs per hour.

The health situation was precarious, many suffered from tuberculosis and even leprosy and they were treated by prisoner of war doctors repatriated to France because the Geneva Convention provided that prisoners of war be treated by doctors from their camp. These prisoners of war-doctors were externalized, they lived in town, were prisoners on parole and had a pass.

About half of them worked in German agriculture, where food supplies were adequate and controls were lenient.

There are few traces of Stalag VI D in Dortmund which was created in October 1939. The “Stadtarchiv” (city archives) do not hold the camp archives, destroyed in the bombing of February 21, 1945 and the numerous copies official documents addressed to the various services of the Nazi regime, although very organized, suffered the same fate, accidentally or intentionally. However, in front of the new Westfalenhalle 3B in Dortmund, a stele recalls the existence of stalag VI D, on which is written:

From 1939 to 1945, several thousand prisoners of war were interned in the large hall of the Westfalenhalle and in the surrounding barracks of Stalag VI D. Coming mainly from Poland, Belgium, France, Yugoslavia, the Soviet Union and Italy, they were forced into forced labour, without respect for the international agreements concerning prisoners of war, in conditions unworthy of a man, in armaments, industrial companies, mines, the private sector and communities. Thousands of prisoners of war died as a result of disease, deliberate acts, malnutrition and the bombardments to which they were exposed without protection.

However, the number of prisoners who passed through Stalag VI D is estimated at 77,000, this figure covering the work kommandos (outside the camp) and the men remaining in the camp, at around 10,000.

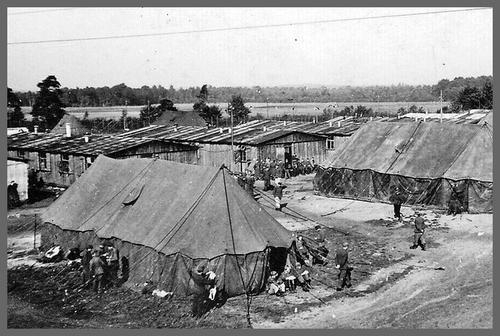

In 1940, the camp was held in the oval part inside the Exhibition Center. The prisoners slept in three-person bunk beds.

But the situation changed quickly with the offensive against the Soviet Union. The construction of a camp made up of barracks was then undertaken, located in place of the current exhibition halls. The camp covered approximately 17 hectares with a double barbed wire fence. The camp then included 40 barracks for prisoners, a surveillance barrack, one for the kitchen, one for decontamination, one for isolation and a few for passing prisoners. The camp was then divided into three zones: zone A for the French prisoners of war, zone B for the Serbian prisoners, and zone C for the Soviet prisoners.

From 1940 to 1945 the health situation in the camp continued to deteriorate. It is not possible to precisely quantify the number of deaths at the camp, but it was certainly high.

Stalag VI D was visited by delegates from the ICRC (International Committee of the Red Cross) and the Scapini Mission (Berlin Delegation of the Diplomatic Service for Prisoners of War) on several occasions. They describe the state of the barracks as defective and sometimes deplorable: disjointed boards or roof in poor condition, the roof allowing the passage of melted snow. In almost all the barracks the PWs would be crowded together.

On the night of February 20 to 21, 1945, Stalag VI D, already hit by two air raids in May 1943 and May 1944, was completely destroyed by a new bombardment causing 32 victims among the Prisoners of War, 1 French, 1 Italian and 30 Russians. But Stalag VI D would not be transferred despite the request of the Trustee, Kléber Victoria, the promises of the Camp Commander and the first observations of the delegates of the ICRC (International Committee of the Red Cross). The stalag VI D suffered a final bombing, on March 12, 1945, which caused more victims among the French Prisoners of War, access for Prisoners of War to the underground shelters of the city of Dortmund located opposite stalag VI D, requested by Warrant Officer Kléber Victoria, having been refused by the Camp Commander with the response “that the President of the Dortmund Police had told him that there were no shelters for the French and that they would have to complain to the Americans and the English.” You should know that the city of Dortmund had the largest civil protection shelters in Europe (24 bunkers distributed throughout the neighbourhoods and a tunnel system).

One of the quirks of fate was whether Jack Pearce had been involved in any of the raids on the industrial heartland and marshalling yards of Dortmund and the camp where Yves was held. Jack and 550 Squadron were not tasked with a raid on Dortmund on any of the dates mentioned, and in the case of May 1944 he was himself on the run in France, and by 1945 had been redeployed to Coastal Command.

A summary of the raids on Dortmund (and by default Stalag VI D) are as follows:

20/21 February 1945. Night attack against Dortmund.

Bomber Command War Diary: 514 Lancasters and 14 Mosquitos of Nos 1, 3, 6 and 8 Groups attacked Dortmund. 14 Lancasters lost. The intention of this raid was to destroy the southern half of Dortmund and Bomber Command claimed that this was achieved.

12 March 1945. Night Attack Against Dortmund.

Bomber Command War Diary: 1,108 aircraft – 748 Lancasters, 292 Halifaxes, 68 Mosquitos attacked Dortmund. This was another new record to a single target, a record which would stand to the end of the war. 2 Lancasters lost. Another record tonnage of bombs – 4,851 – was dropped through cloud on to this unfortunate city. The only details available from Dortmund state that the attack fell mainly in the centre and south of the city.

Yves was repatriated on April 10, 1945 and demobilized on June 6, 1945.

According to Joël, his son, Yves never spoke of his imprisonment, Joël simply knows that his mother corresponded with him during the war and that is how they met.

When the prisoners were repatriated to France in 1945, the atmosphere was not happy. Many returned in indifference and contempt. Some prisoners were accused of allowing themselves to be captured rather than die for their country. Many found it difficult to talk about what they had experienced and preferred silence. We will, of, course, now, never know the reason for Yves’ silence.

According to another member of the family Yves’ brother, Berty, also a prisoner of war, was happy in a German family in the countryside where he was well fed while his brother had to eat grass for food.

I did not find Berty on any list of French prisoners.