Remembering Uncle Harry. Because almost nobody else has….

This one is a bit of a mystery I’m afraid, and as sad a tale as there is in the family vault.

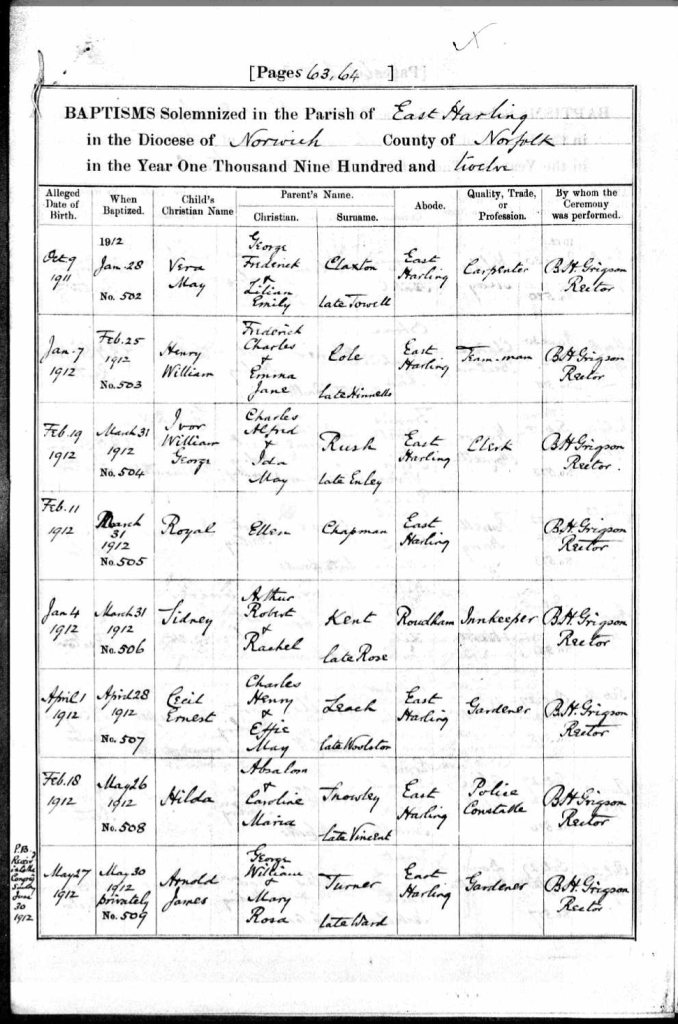

January 7th is the anniversary of the birth of great uncle Harry.

Henry William Cole was born in 1912, at East Harling, and was the third child of eight to my great grandparents Fred and Emma Cole, and an older brother of my grandfather.

I was too young to remember great grandad Fred Cole, and great nan Emma had passed long before I came along. I only missed Harry by a couple of months, but the sadness of his story suggests he’d been lost long before that.

For various reasons, he’s the one who nobody seems to mention or not know very much about. Even Dad when he was alive didn’t know much about him, even though he’s buried close to the rest of the forebears in East Harling churchyard, and although I’ve got used to researching the corners of family stories for clues, little has turned up that’s eased the frustration.

After his baptism, I know nothing about his life other than he appears on the 1921 census, aged 9, living at home at West Harling Road with the family and a boarder while great grandad Fred was head horseman at Middle Farm.

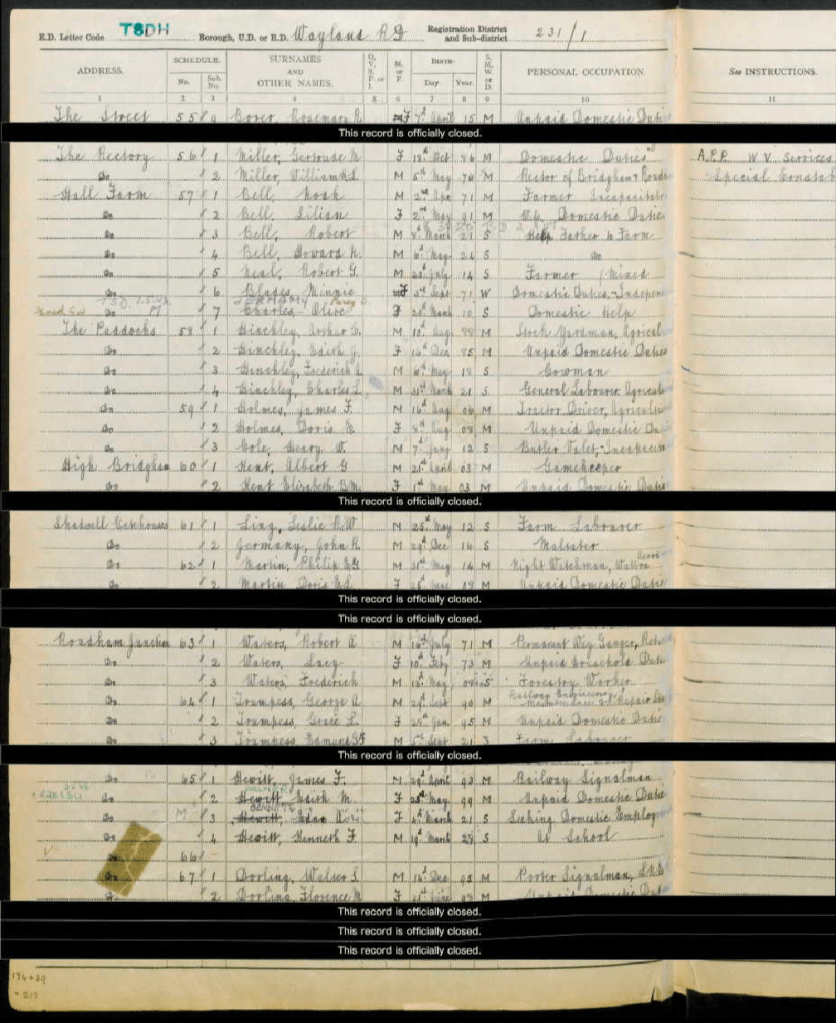

He next appears in the 1939 Register, living at The Paddocks at Bridgham. What is interesting is that although he’s by then aged 27, he’s apparently living with his older sister Doris and her husband Frank. The census shows the Hinckley family are the employers at the farm, and Harry is described as a butler/valet.

Harry never married or raised a family and there’s never been any information about any relationships, and I don’t see him on any electoral rolls. It’s like he existed in a void until just before the second world war.

One clue that stands out in his 1939 entry is the word ‘incapacitated.’ Now I know that the 1921 Census was the first census not to ask questions about disability, and that the incapacity in that context can refer to mental or physical disability, or simply being unfit for work, but the 1939 reference could add weight to one of the few insights I have about him.

With nobody left who knew him well to ask, it was inferred that Harry might have been autistic or at least within the spectrum of the many conditions that we now understand better than we did 85 years ago. In any case, that rumour is all we have. I know it’s impossible to gain an insight about someone’s personality from a picture, so we have to look elsewhere for conclusions. In my other blogs I’ve touched on his mother Emma and references that she ‘suffered with her nerves.’ I’ve no idea if this has any relevance to Harry’s character.

The picture we have of Harry as a butler is undated, but he looks very young. Dad suggested that he trained as a valet in London, but there’s no record of that, and we already know that by September 1939 he was back in Bridgham. So where did he go between leaving school and the outbreak of war? It seems likely he was ‘in service’ somewhere, but we simply don’t know anything about his teens or early twenties.

War Comes Calling

Whatever his status or capacity in the month that war broke out, we do know that Harry went on to serve in the army, albeit with little detail about his time in the forces.

Family lore is that he served as a stretcher bearer in ‘the medical corps’ in India. The picture above certainly supports his service in the Royal Army Medical Corps, but frustratingly, there’s no record of him in the recent tranche of Medal Cards released by Ancestry for World War II, because it appears record cards for the RAMC (amongst several other units) didn’t survive.

There’s more to do on that line of enquiry, but I can’t confirm where or when he served, and I don’t have a service number or sufficient detail to make an application to the Ministry of Defence worthwhile at this point – especially as it might take months to get an answer, so importantly, we don’t know when he enlisted or anything else about his war. It’s almost as if Harry has been shelved in history, and perhaps this is what intrigues me most about a man who might not have been equipped mentally or emotionally for military service, but was selected anyway.

I really don’t know what to make of the lack of information about him in the family story. I’ve only got a couple of elderly aunts and an uncle who survive, but they don’t know or remember anything about him other than he was adversely affected by his experience in the war. The lack of military records due to insufficient detail about him makes research complicated until the National Archives and Ancestry release more WW2 files over the next couple of years.

The Spiral

As was the case before the war, there’s a knowledge gap after 1945 until the final chapter in his life.

What the family history does tell us though is that the war had a profound effect on his mental health. It is suggested that Harry tried to go back to working as a butler in London but was unable to hold down a job. From there he drifted and spent time in St Andrew’s Hospital in Thorpe St Andrew near Norwich. Is this true?

With a lack of family sources to add to the standard public records, and with the current unavailability of military details, I turned to the Norfolk Record Office to see if they held anything about Harry in the St Andrews Hospital records. Opened in 1814 as Norfolk County Asylum, it was renamed in 1920 as Norfolk Mental Hospital before becoming St Andrew’s in 1923. Although it’s long ceased being a medical facility, you can still find the sprawling site on Yarmouth Road as you leave Norwich.

So what did the hospital records reveal?

The very helpful Norfolk Records Office staff at County Hall quickly put me on the right track and researched the St Andrew’s files for traces of Harry and found references to him in a number of sources.

Patient Indexes SAH573 and 574, Medical Register SAH 243, and an admission record SAH587 all mentioned Harry, as does a ward index SAH1362.

Some of the records are incomplete, or too fragile to handle, so we don’t have a complete picture of Harry’s time there, but it seems Harry was a ‘certified’ or involuntary patient from March 1st 1945. As we don’t have his service papers, we can’t comment on the context of how his admission might align with his discharge from the army before war’s end.

Harry was admitted under the reference 17095, with a sub-reference of C2462 which is probably his ‘certified’ number.

Unfortunately the records don’t show all his movements, but the ward index SAH1362 confirms he was still a resident on 16th May 1958. We don’t have much else to go on, but he’s later shown as being readmitted on 4th February 1960. In the absence of any trace of him in the discharge books it seems likely that he had remained a resident from March 1945 until at least 1958, if not longer. There’s no record of how long he’d been out of hospital before his readmission in February 1960, or how long he stayed thereafter.

There’s one sad anecdote, that at some point in the late 1950s, Harry turned up at my grandparents home in East Harling. He’d been trying to find their address by asking in the village. Whatever the reason for the visit, it ended with an angry Harry being returned to the hospital by the police.

The End

With no further details available between February 1960 and 1963, we can only surmise that after several years in hospital, Harry had at least at some point rejoined the community, successfully or otherwise, but crucially we don’t know when he left St Andrew’s for the final time.

We do know however that the final period in Harry’s life saw him back in London.

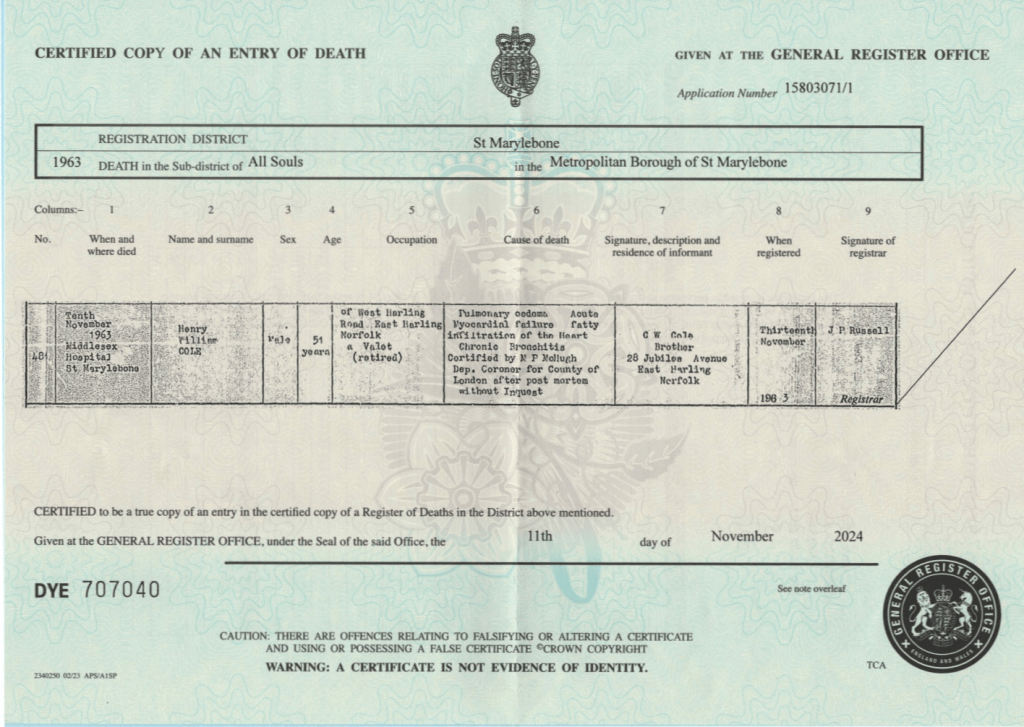

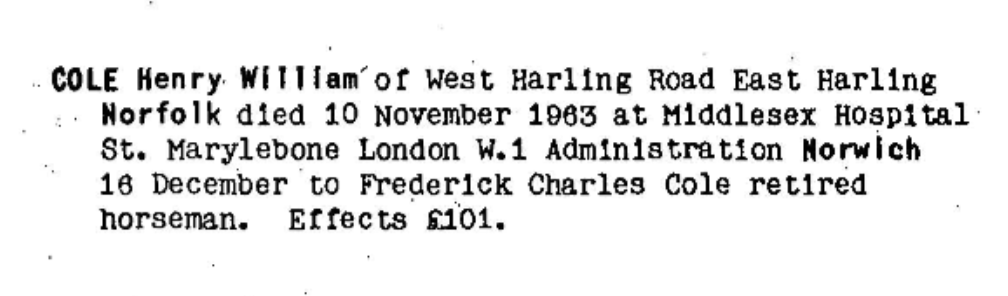

It was there he was apparently found seriously ill on a park bench in Regents Park suffering from chronic bronchitis and heart disease, and he died at the Middlesex Hospital on 10th November 1963.

There was no inquest or inquiry. Harry was aged 51. There’s a suggestion that he might have been sleeping rough in the period before his death, but such was the veil of silence in the family, Dad had even wondered if Harry had taken his own life. We now know that wasn’t true, but whatever the truth is, the official record suggests nobody was interested enough to record why a man might be allowed to end up in such a desperate situation. The only documentary narrative I’ve found about Harry is the newspaper report carrying his obituary, leaving us to very much read between the lines.

With so many gaps in the family story and perhaps the fact that my grandparents didn’t want to discuss the events after the war means there are many closed doors when travelling backwards down the corridors of time. I’ve known and remembered several of my fathers uncles and aunts, some of whom lived to great old age, but it was never likely to be appropriate for us ‘youngsters’ to ask the difficult questions or turn over too many stones. It’s why so much history disappears as the generations pass.

Even so, as I’ve long since decided all this history needs recording, I’m hopeful that more military records will soon be freely available to help me understand how a probably fragile young man ended up involved in the war and what happened to him to see a complete collapse in his mental health by the age of 33.

Harry’s story, albeit incomplete, and lost in time, is such a modern topic as we are now much more aware about our veterans and the safety net required to catch those who fall, and I hope this story adds weight to the care and support of veterans. Embarrassment, shame, lack of understanding or whatever the barriers are, hopefully things have moved on.

It’s too late for Harry, and there’s much more we can do for those like him, but the least we can do for him is remember the lost boy from East Harling.

Addendum:

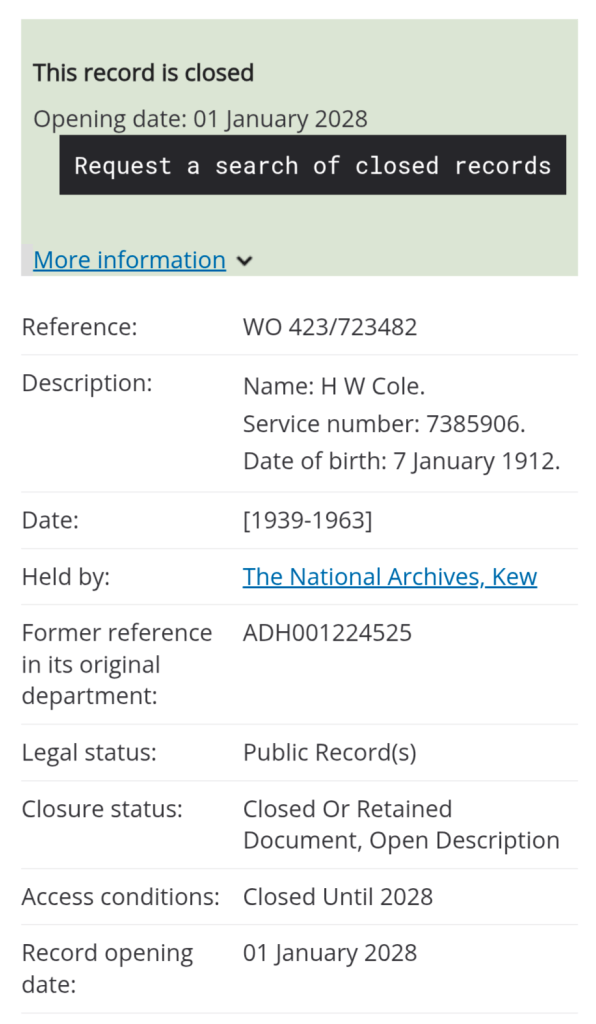

Having had a great deal of feedback about the life of uncle Harry, I decided to apply for his service file from the Ministry of Defence. I received a surprisingly swift response telling me that his files are now in the hands of the National Archives, and that I should apply to them. As the process of transferring almost ten million World War Two records will complete over the next few years, and Harry’s file is apparently not scheduled to become open until January 2028, I’ve fired off my application under the Freedom of Information Act and have to allow for a ‘sensitivity review’ as it’s less than 115 years since Harry’s birth. We await a result.