Here I am, having not posted a blog in ten months, posting a second tale within 48 hours.

A collection of other hobbies and distractions means I’ve not sat down and cleared the locker of stories that, from time to time, I’ve discussed with friends and acquaintances and either partially researched or intended to come back to, to add to my collection of tales about local lads that went off to the Great War.

Will Fake is one such soldier, and although I’ve discussed him with his descendants Andrew and Ben, who I’ve known for years, I’d not got round to writing about him. It’s also the season of remembrance so there’s never a better time to put faces to the names carved on the white stone memorials, soon to be adorned with poppy wreaths.

But, having said all that, the one thing about Will Fake that always grabbed me was his picture.

There are never many sources on individuals that survive in the archives from the Great War, unless you are lucky.

Often all that remains is a photograph. Again, these are usually family heirlooms in better or worse condition, sometimes with inaccurate names or facts scribbled on the rear long after the event by a relative who’s made a guess that it’s said uncle ‘when he was in the war.’

Occasionally there is detailed context that tells the story of a man (boy) from long ago, but often all you get is a standard portrait of a fresh faced lad in his new service dress, posing in front of a photographer’s drape. The fashion often included a swagger stick, something that an ordinary rank would never possess outside that moment, frozen in time, as a parting gift to his mother.

But what has always struck me about the picture of Will Fake was not only the quality of the picture, but just how young he looks. I’ll come on to his age shortly, but he looks younger than his years.

If you’ve read any of Richard Van Emden’s books you’ll know of the concept of ‘boy’ soldiers and that many served well below the age of 18, although the recruitment criteria was simply that a lad had to physically be ‘apparently’ of the right age on attestation, and clearly a great deal of latitude was allowed.

But look into Will’s eyes; man or boy. You can decide for yourselves.

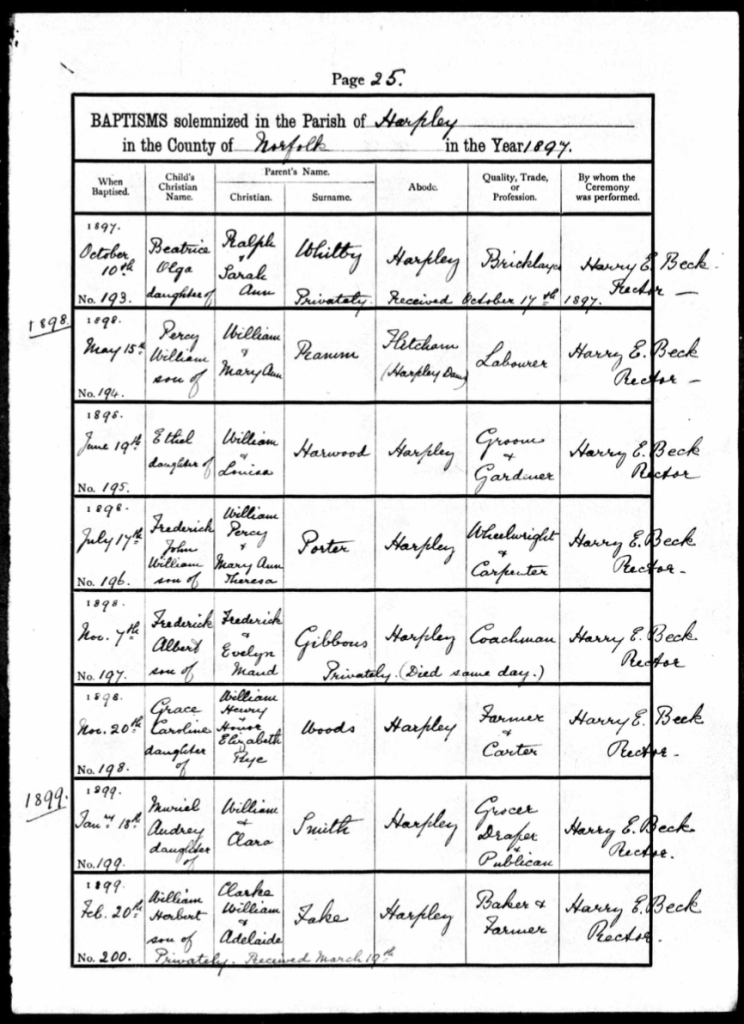

William Herbert Fake was baptised at St Lawrence’s Church, Harpley on 20th February 1899. Harpley is one of those pretty little villages out between King’s Lynn and Fakenham and lies on the fringes of Houghton Hall estate.

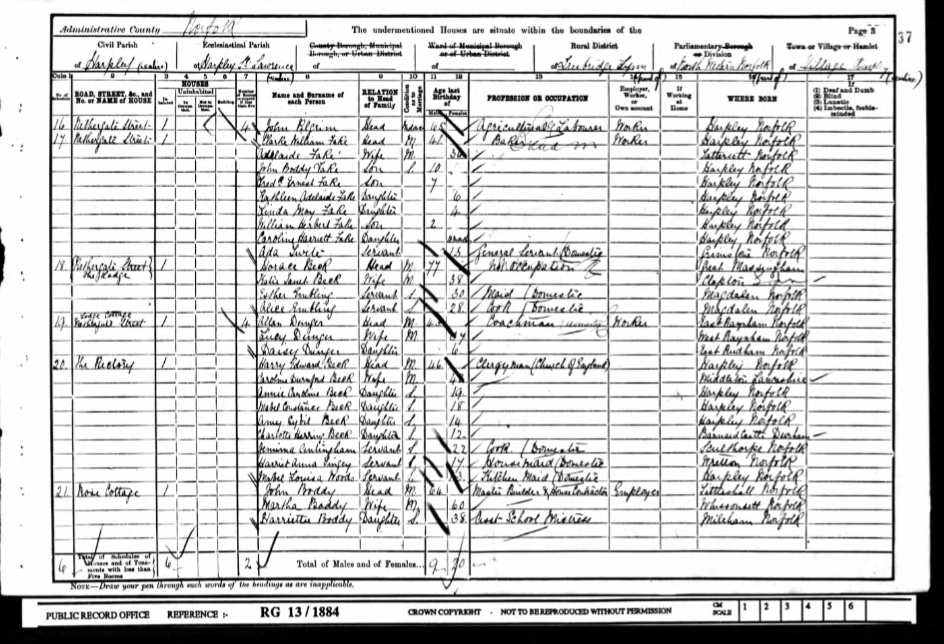

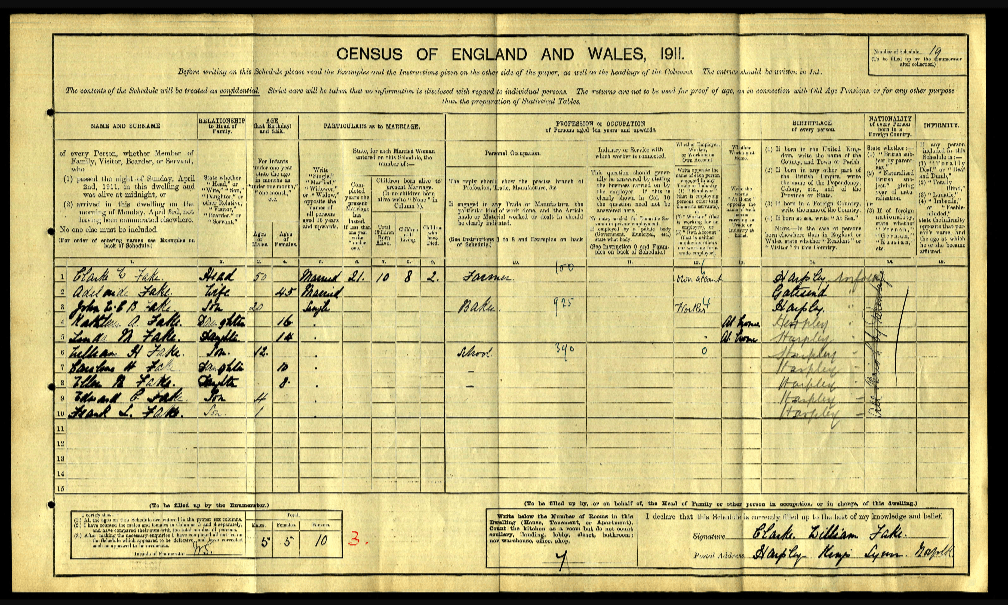

Will was the 5th surviving child of Clarke and Adelaide Fake, of Nethergate Street in Harpley – baker and farmer by trade.

You can see from the 1911 census that the family had expanded, and life would have been pretty ordinary for lads on the farms of west Norfolk in the years before war came calling.

So what do we know about Will and his journey to war? As often is the case, we know more about the end than the beginning.

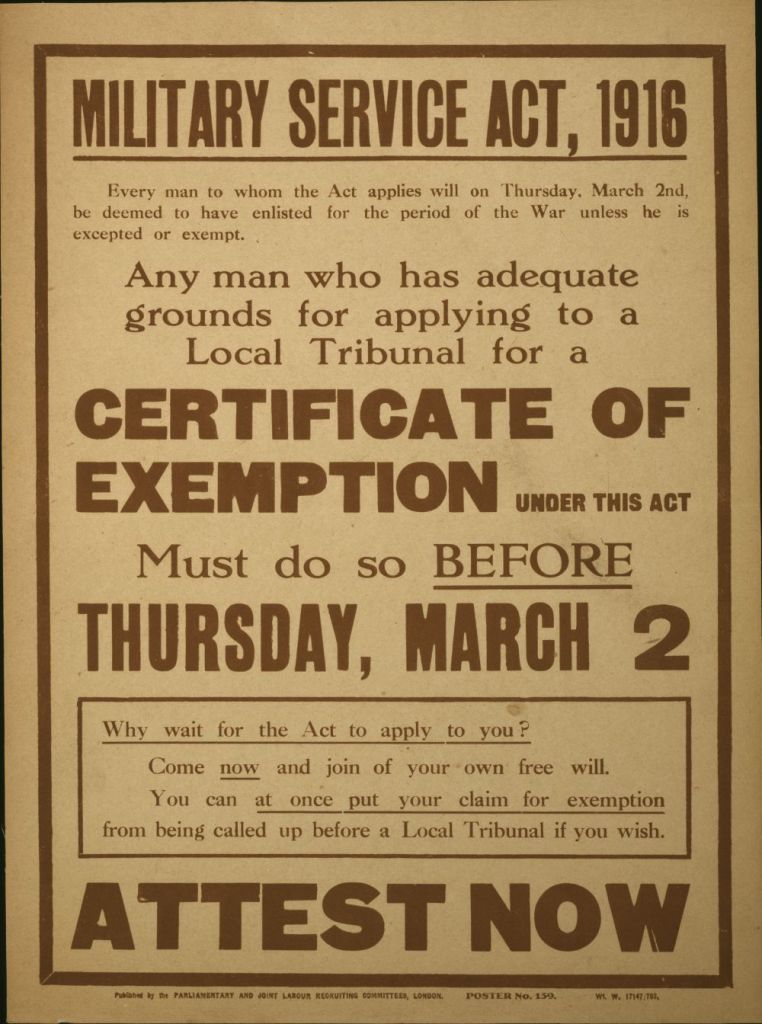

His service papers do not survive, but as a presumably fit and healthy young man, by the time he came of age the Military Service Act of 1916 had long been in force after volunteers began to dwindle, so Will probably didn’t have much choice but to enlist. From September 1916, a vast pool of two hundred thousand young men were under the auspices of the Training Reserve, later organised into Graduated and Young Soldier Battalions affiliated to regiments.

We don’t know exactly when Will stepped forward, but his archive holds a reference to a Training Reserve service number of 75294, which most likely belonged to the Royal Fusiliers (City of London Regiment) and that he attested at King’s Lynn.

What we do know is that Will was renumbered as GS/75152 on joining the 17th Battalion Royal Fusiliers (City of London Regiment). From research around other men with very close numbers to Will, it seems likely that he joined the service battalion in January 1918, around the time of his 19th birthday, at the point he became eligible for overseas service. We can deduce from this timeline that Will probably entered the reserve around 9 months earlier.

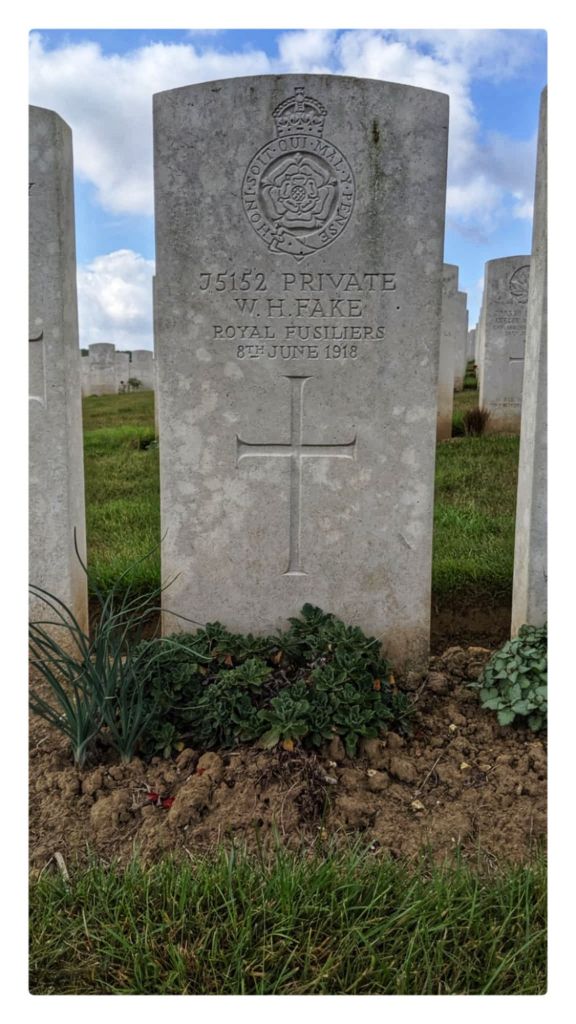

I have rather given the game away in the above image, but what do we know of the rest of Will’s war?

We need to look at a number of sources for clues about his journey to the front. Firstly let’s look at the Medal Index Cards and Medal Rolls.

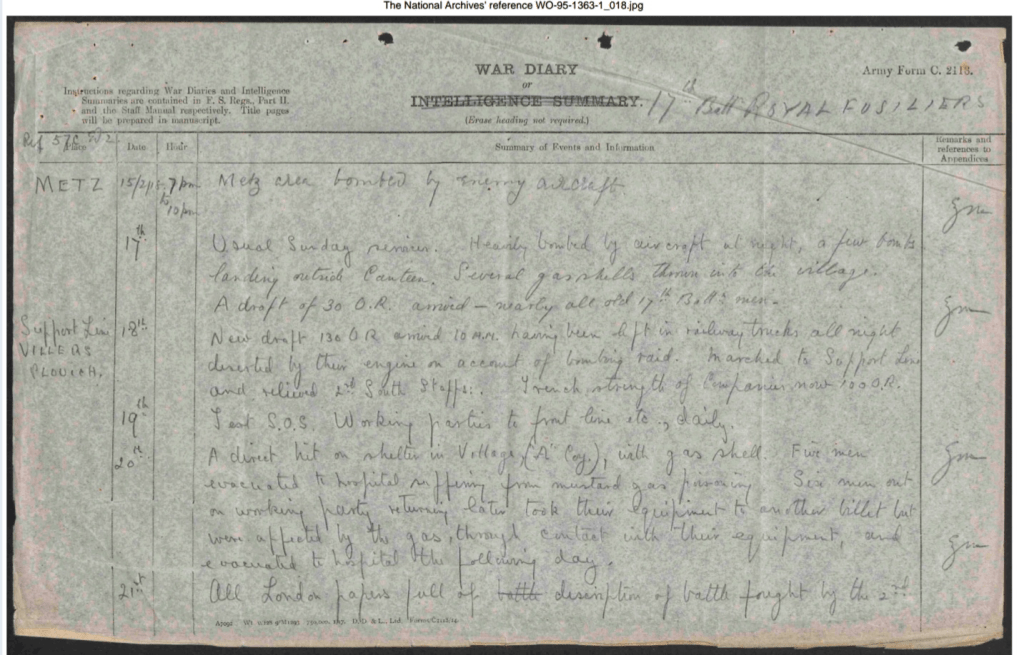

The medal records are often helpful in giving us a date for when a man arrived in a theatre of war, and in this case we can see Will embarked to France on 15th February 1918. Looking further into the war diaries of the 17th Battalion, we can see that a draft of 30 men arrived on Sunday 17th February and another larger draft of 130 men on the following day; so we can be reasonably confident that Will’s first experience of life on the western front was in the support trenches at Villers Plouich on the Somme battlefield.

February was spent in the front line expecting a German spring offensive – a big push to the sea to finally break the deadlock in the war. Will would have been aware of what was coming, but the British were caught by surprise on March 21st when the Germans sprang their attack. Will and the 17th Battalion were in the rear lines, resting, when British front lines began to crumble, and as forward units began to fall back and fight a rearguard action, Will and his comrades were called forward to help bolster the desperate defence as the British army sought to slow the advance.

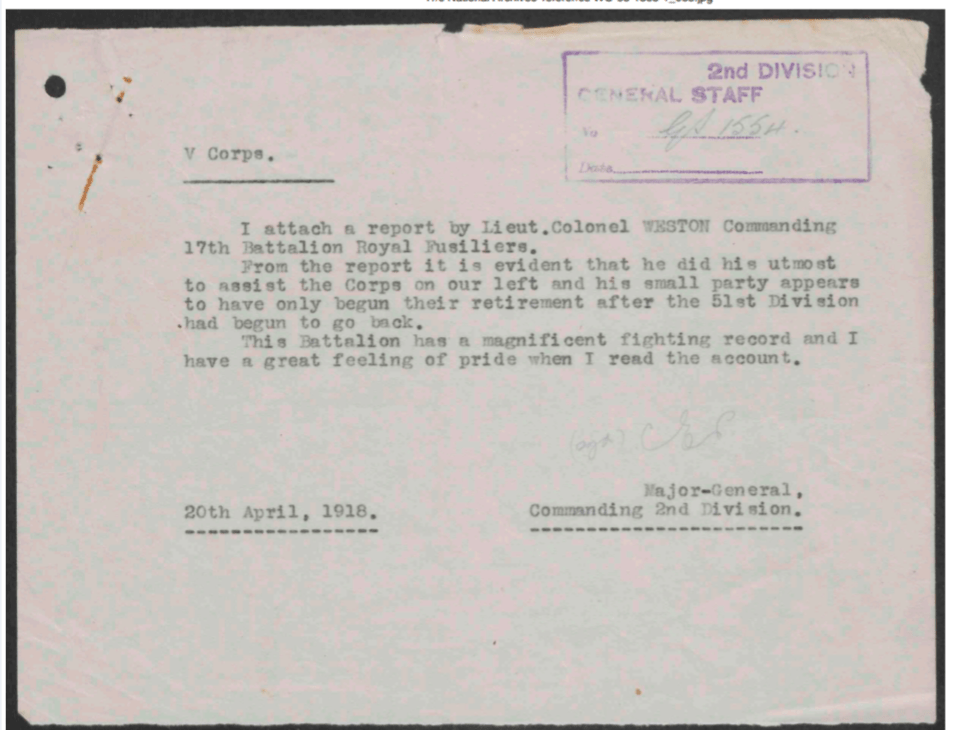

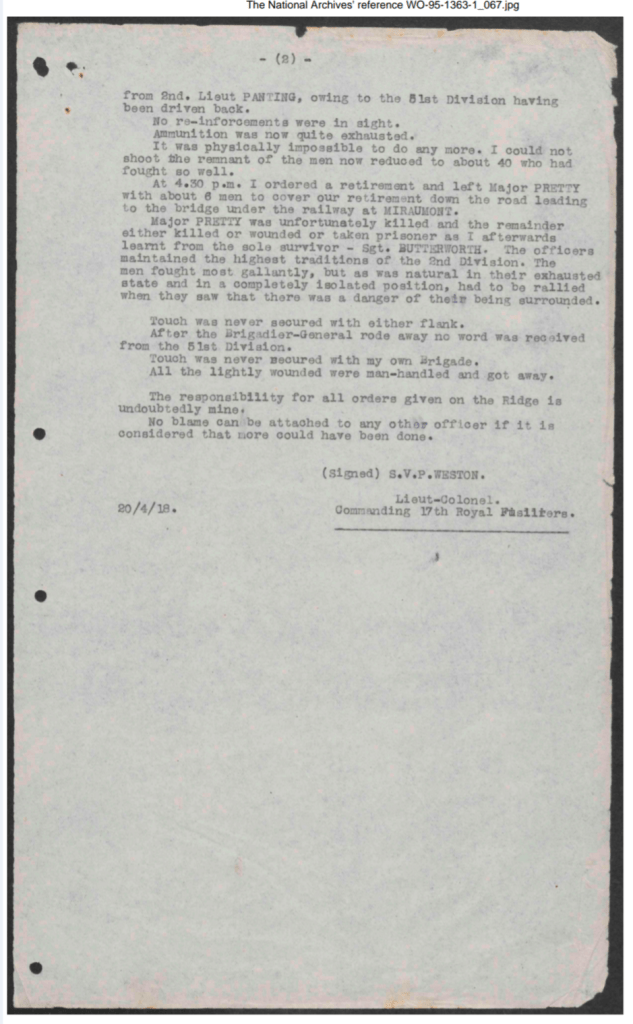

I won’t go into detail about the chaotic scenes and precise movements of the 17th, but below I’ve included a report which is one of the more remarkable ones I’ve read of any unit.

Clearly there were retrospective reviews as to whether enough had been done to foresee the German attack, and whether, in the case of the 17th, they’d been up to the task.

I’m actually not sure if any particular Brigadier really inferred that officers might consider shooting their men if they failed to hold the line, but I’ve not seen a clearer example of how tempers were obviously raised in the recriminations that followed a near disaster.

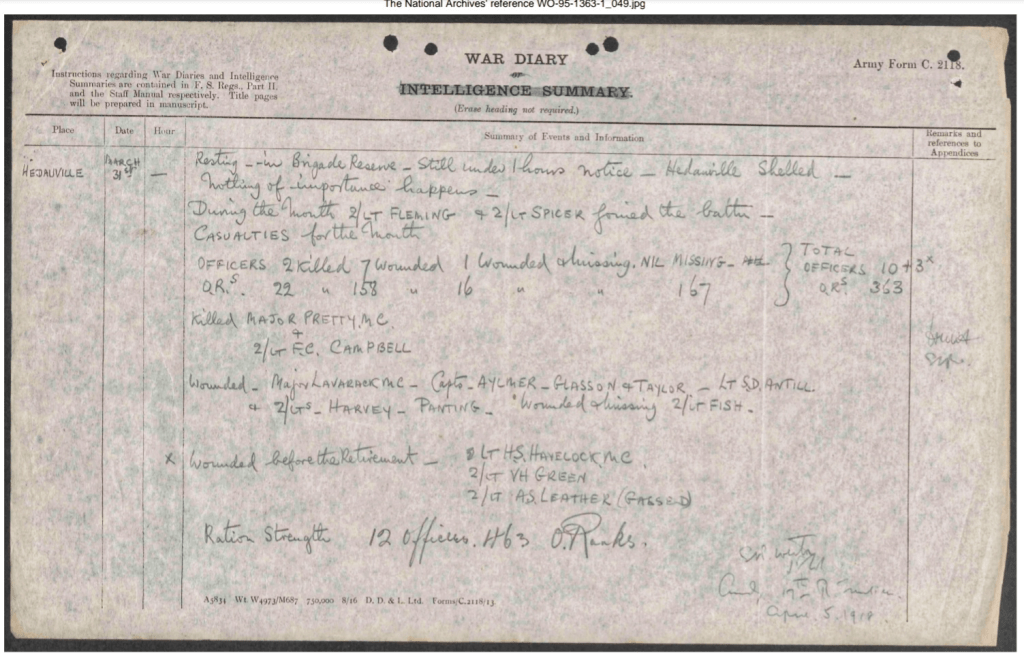

The final extract from the March 1918 diary gives casualty figures of over 370 men of all ranks for the month, of which 167 were missing. It had been a tough baptism for Will.

When we look back to the picture of young Will, we now know that that fresh face had grown up extremely quickly in his first six weeks at the front.

So how did his war end, as we know he didn’t survive?

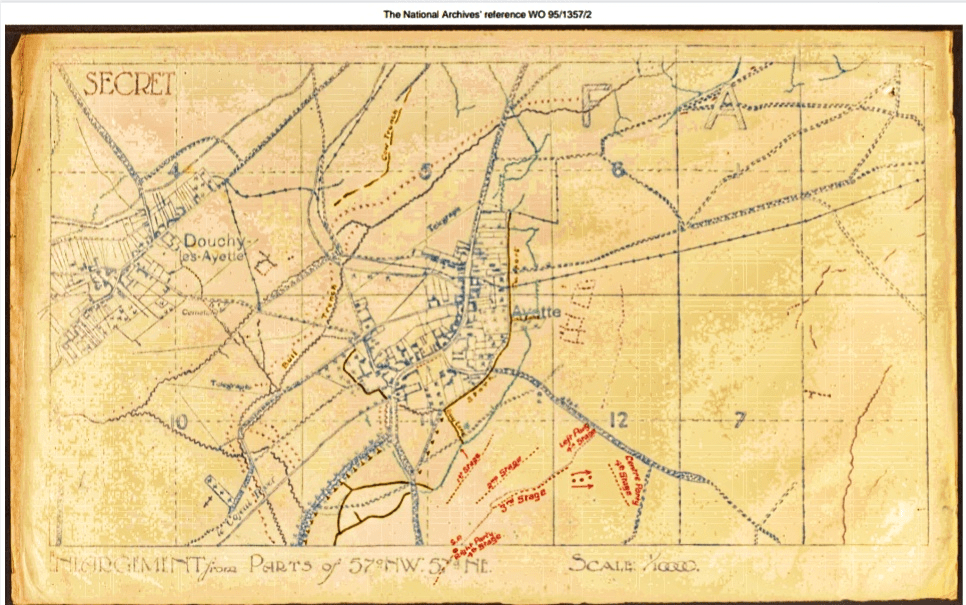

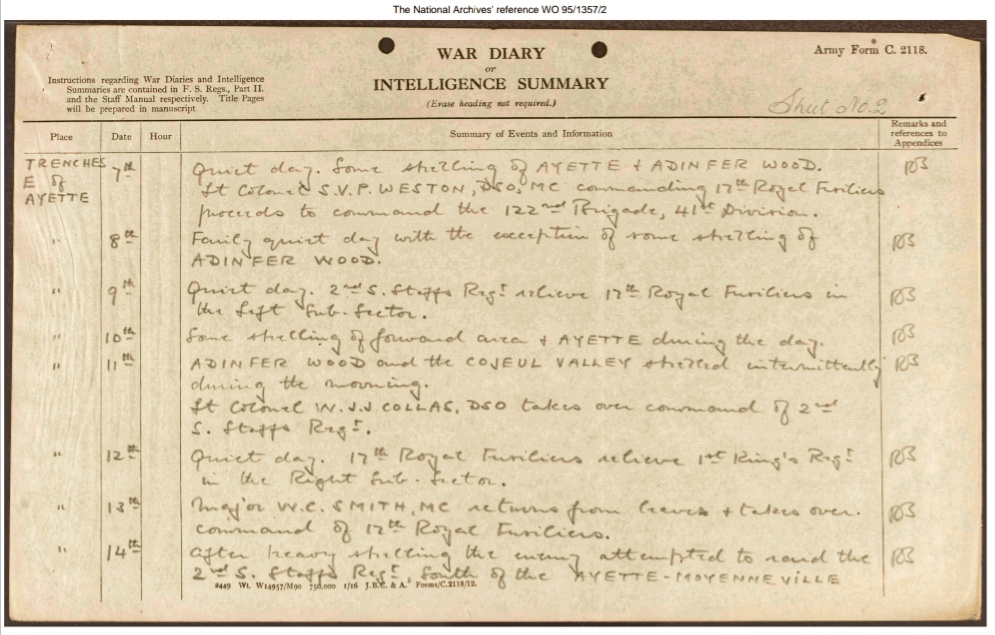

We need to move forward to the first few days of June 1918 when the 17th Battalion were at Barly, preparing to move forward into the front line at Ayette. 6th Brigade had spent June 5th preparing for the move and the 17th Battalion had played football against the 1st Battalion the Kings Regiment. I don’t know if Will was a footballer, but the result was a 2 all draw.

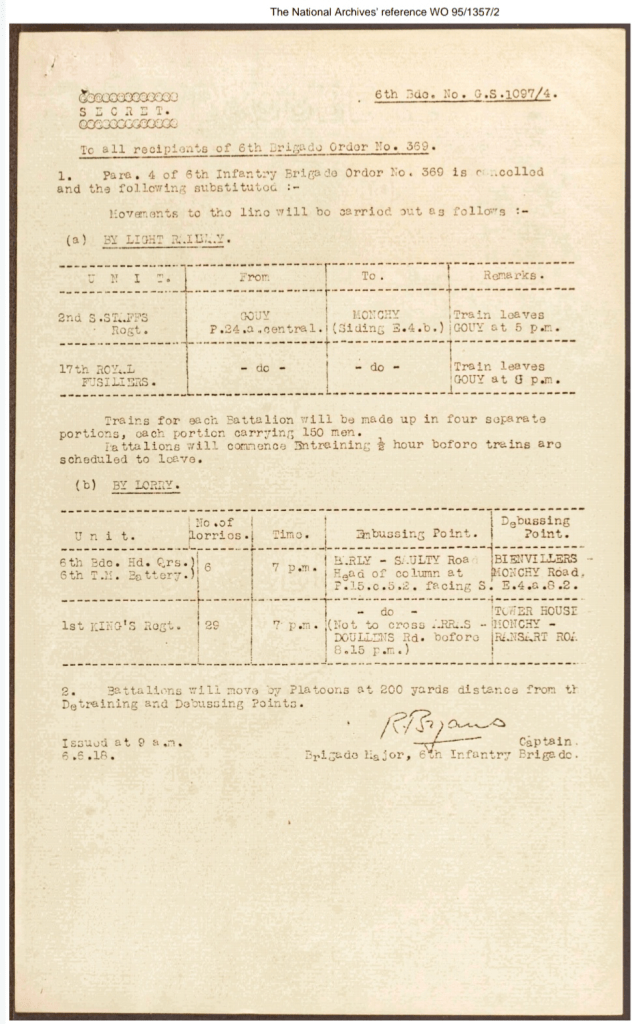

What we see from the diary is that the battalion paraded at 6pm on June 6th, then later entrained on the light railway towards the front, where they would relieve the 2nd Battalion Grenadier Guards at about 1030pm.

As always, each side would be aware of the routines of relieving the front, and would be looking for opportunities to shell troop movements.

Will and his battalion would travel up to the support lines by light railway to Monchy au Bois before making the final journey of a few miles on foot as the darkness gathered on that June evening.

The 17th Battalion diary states:

“The battalion was heavily shelled on marching to the line – one officer 2nd Lt Spicer and 9 men being killed and 10 wounded. Relief complete 2.20am”

The diary of the 2nd Battalion Grenadier Guards tells a similar story for their changeover on the late evening of June 6th, as they suffered casualties of their own.

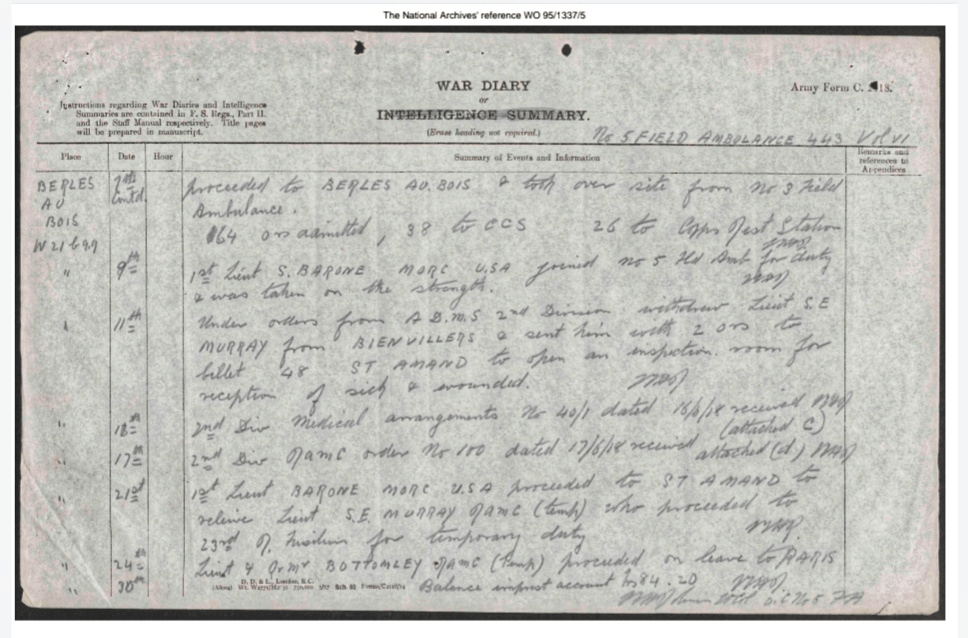

The 17th Battalion diary for the 7th June is silent on casualties. However the 5th Field Ambulance, operating for the brigade, tells a different story, with 64 casualties collected in that section, 38 of which were evacuated to the Casualty Clearing Stations. There is no mention of Will or any incident, which isn’t uncommon.

The 6 Brigade war diaries tell us no more than the other units, although this is where the details are contained of the logistics involved in putting so many men into position at Ayette for that phase of the war.

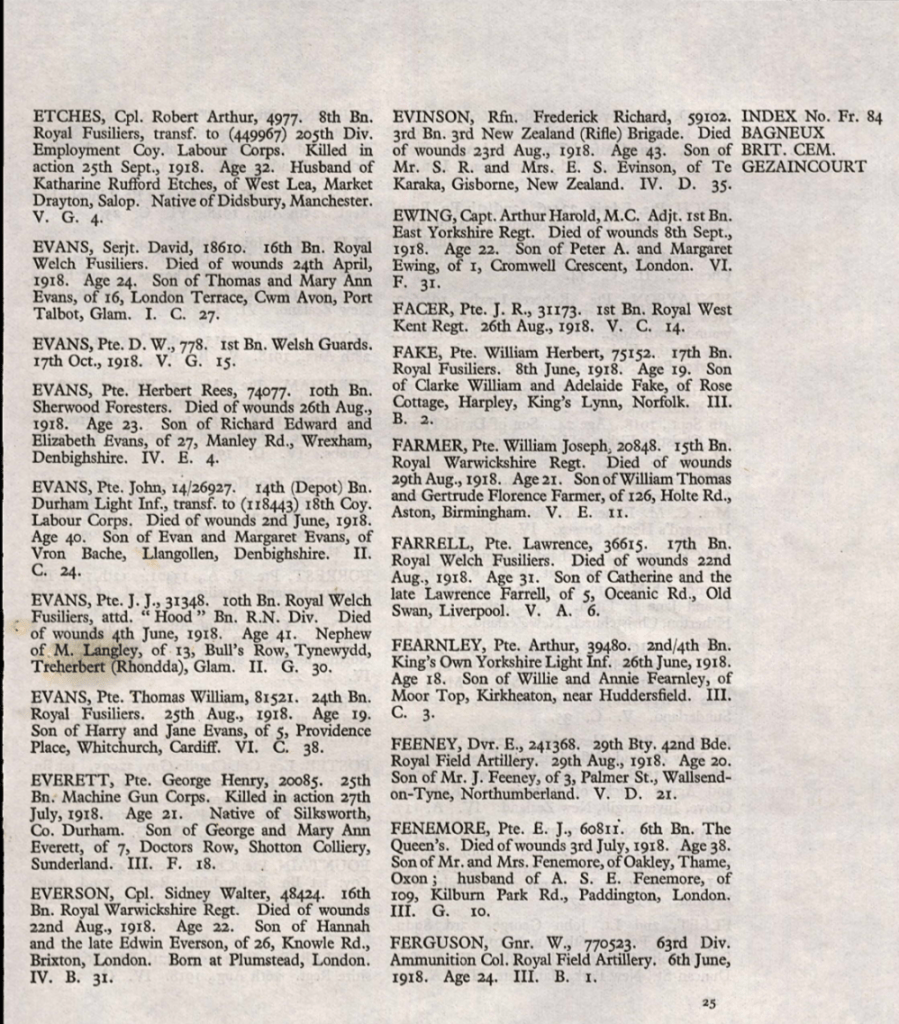

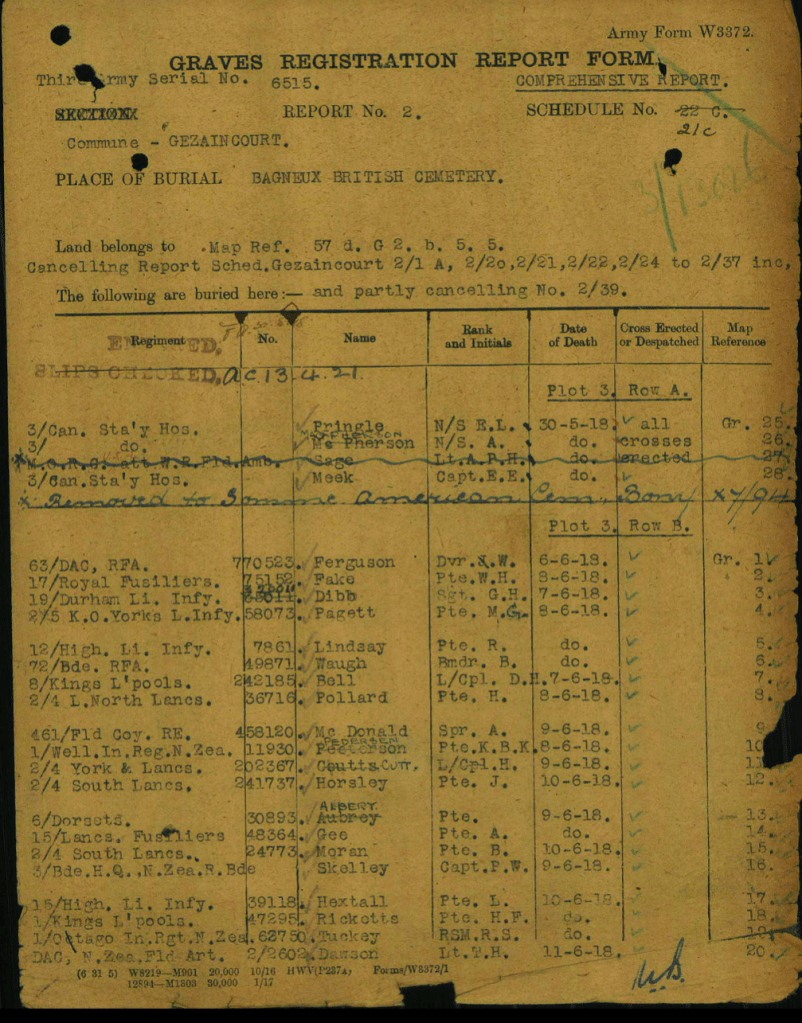

What the casualty records from the 5th Field Ambulance show is that at some point, possibly late on 6th June, or on the next day Will Fake received a gunshot wound to the head. How soon after arriving in the line he was shot isn’t clear, but he was then evacuated to a Casualty Clearing Station at Gezaincourt where he died of his wounds on June 8th.

So what do the casualty records tell us?

It’s clear that the sector was heavily shelled as the 17th relieved the Coldstream Guards, as both units lost men in similar circumstances on changeover, but the field ambulance report is explicit about a gunshot wound to the head, and that he was admitted on 7th June. From this we can probably deduce that Will made it to the front line having avoided the shelling, but was picked off at much closer range by a shot fired from the Großherzoglich Mecklenburgisches Füsilier-Regiment Kaiser Wilhelm Nr. 90 who were posted opposite.

We can only imagine if Will was singled out by a sniper or was the victim of a less discriminate shot.

Will is buried alongside 1371 other fallen at Bagneux British Cemetery at Gezaincourt, which is close to where casualty stations stood.

His mother received his effects after his death.

Will’s war was at an end less than four months after it had begun, and back home a family was left to come to terms with the loss of a son and brother. An older brother, John, was also overseas albeit in the relatively safe role of 25 Squadron Royal Army Service Corps Remounts at Le Havre, but you can imagine the waves of anxiety delivered by telegram to waiting families back home.

So when we think of remembrance this year, as every year, remember in your own way those who paid a price beyond all others; and amongst all those names carved in stone in quiet country churchyards, remember Will Fake.