This is another unfinished corner of the family history, that I’ve mentioned before, but never yet got round to researching properly. It’s a brief biography of yet another of my grandfather’s older brothers, Walter Crooks, and another example of one of the brothers adding an ‘S’ to the surname.

There’s nobody left to ask why Crook became Crooks on an apparently random basis, but here we are – the history is written and it’s too late now.

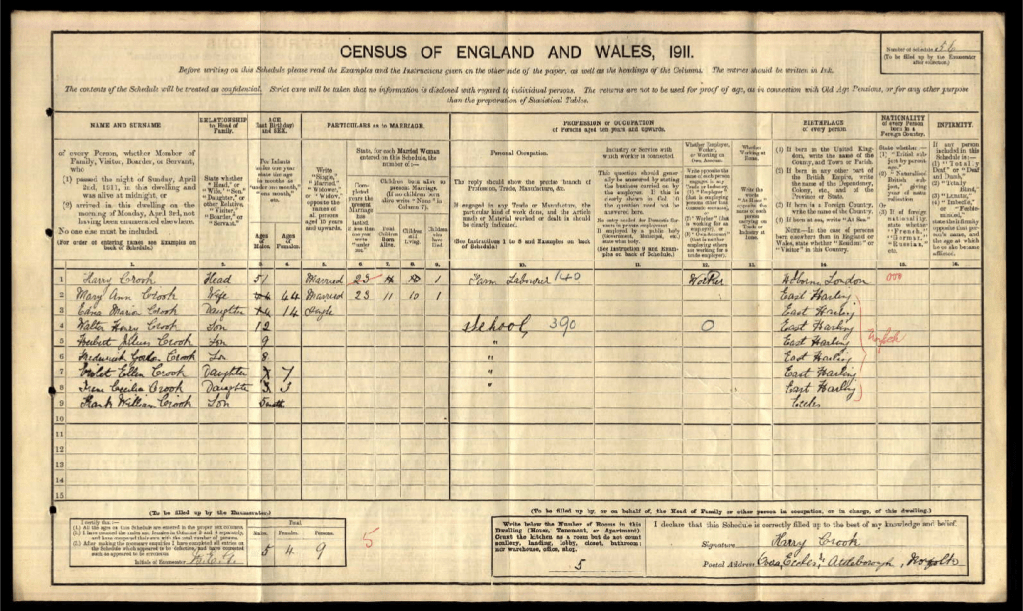

Walter was the sixth child of my great grandparents Harry and Mary Crook, and was born on 30th September 1898 at East Harling, Norfolk.

He’s with the family at East Harling on the 1901 census, and aged 12 on the 1911 record by which time they’d moved the short distance to Overa Farm at Eccles. By this point my grandfather Frank had joined the clan.

I use the word ‘clan’, because there’s a Scottish twist to the tale which we’ll come to in due course.

Almost all my blogs have centered on the military service of my great uncles, and Walter was to be no different – given that his father had been in Egypt with the Royal Artillery in the 1880s (serving 12 years in total) and that older brothers Edward, Harry and Sydney had all served either in pre-war or on the outbreak of hostilities in 1914. It should be of no surprise to learn that Walter also joined up.

I haven’t drilled down into the details of his service, but we know that by the summer of 1916 he was in training with the 3rd Battalion, Lincolnshire Regiment. We know this because we have a record of his transfer from the regiment to the reserve on 11th August 1916, signed by Colonel G A Ivatt.

Helpfully, his conduct is recorded as ‘Very Good’ and he is shown as having served 164 days with the regiment. Volunteer or otherwise, this means Walter joined the Lincolnshires on the last day of February 1916, aged 17 years and 5 months. I assume that due to the strong influences in his family, his parents fully consented to Walter going off to war, albeit slightly under age.

There is a bit of context to what was happening in the summer of 1916. Army Order 203/16 outlined ‘Class W’ men as “all soldiers whose services are deemed to be more valuable to the country in civil than in military employment” and that all youths of over 17 and below 18 years of age who were serving in the army at home would, if willing, be transferred to Class W or W(T).

Walter certainly matched the criteria laid down in parliament that summer, but other than surmising he was employed on the land like the rest of his family, I have no information as to why his release might be so important.

But….

There is a back story to his transfer to the reserve. Older brothers Harry and Sydney had emigrated to Canada and were both in Flanders in the summer of 1916. Harry had been wounded in March 1915 almost immediately on reaching the front at St Eloi with the Princess Patricia’s. Sydney had arrived a while later with the 5th Battalion C.E.F and it was his death on June 7th 1916 that triggered action from their mother Mary.

Just six weeks before his 18th birthday, and probably imminently due for draft to France, Mary allegedly had Walter hooked from the ranks.

Having recently lost a son, her anguish got in the way of Walter facing a similar fate, at least in the short term…

Allegedly…

Whether he’d lied about his age or whether anyone cared, family legend has it that Mary dobbed him in and had him removed due to his age. We don’t have a record of what the letter said, or how young Walter reacted to his mother writing to his commanding officer, but Mary got her way, albeit briefly.

It’s open to debate if the Army Orders on Class W men was a convenient loophole to allow a worried mother her way, or if Walter was simply stood down briefly due to army policy prevalent at that specific moment and the legend is just that.

I suspect it’s another tall tale from family history.

You can read about Mary at the link below

I can only imagine how he felt after almost six months preparation and what his mates might have said when his mum wrote a note to the boss!

Whatever happened between mother and son, the effect was futile, as Walter turned 18 at the end of September and was free to choose for himself.

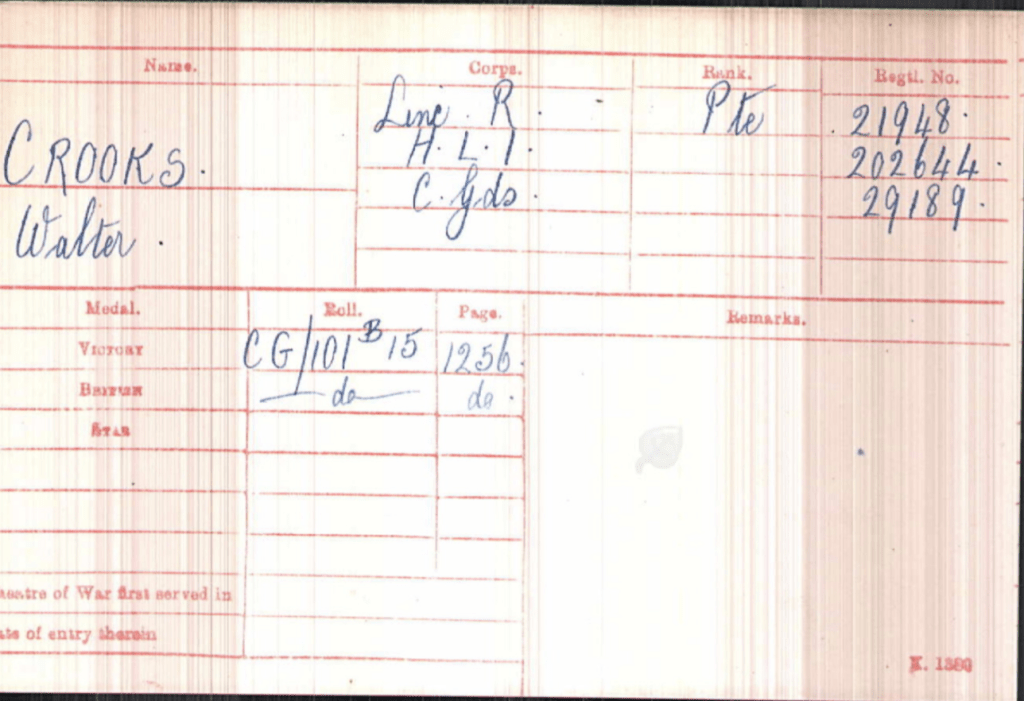

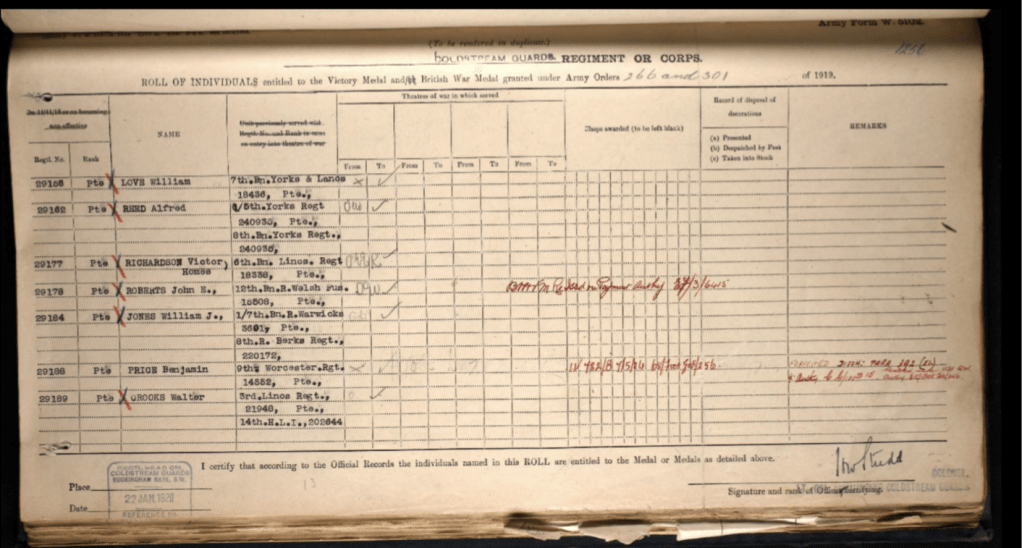

As you can see from his medal index card and medal roll, Walter went straight back to the army and re-enlisted, serving out the war with the 14th Battalion, Highland Light Infantry.

Unusually for the family, there are absolutely no surviving family anecdotes about his time at the front, so all I have is the generic history of the 14th HLI.

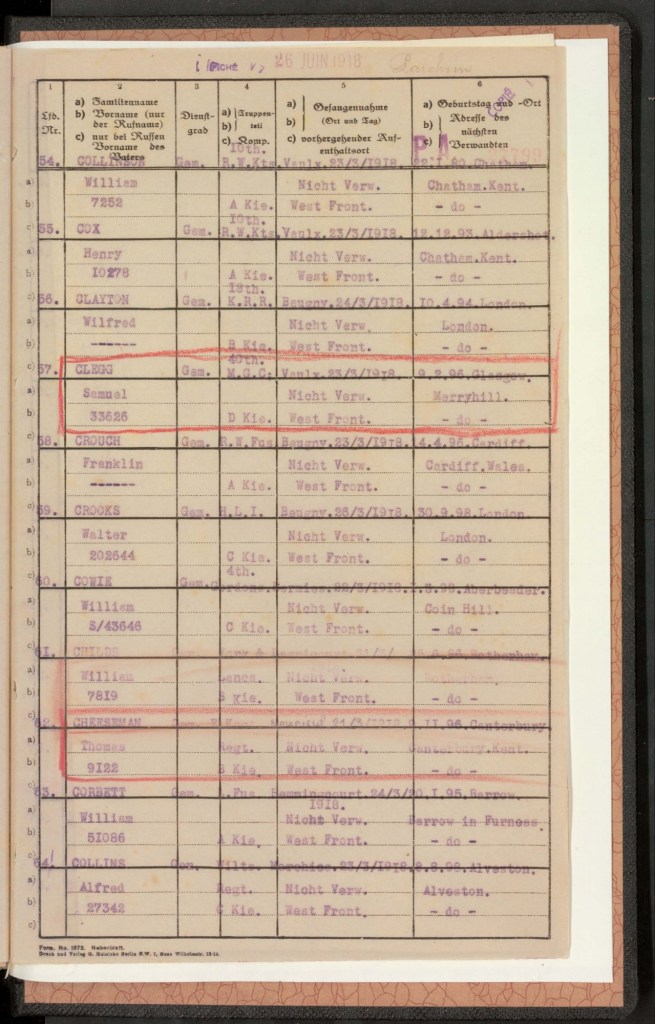

What we do know though, and it has entirely escaped family memory, is that Walter became a prisoner of war.

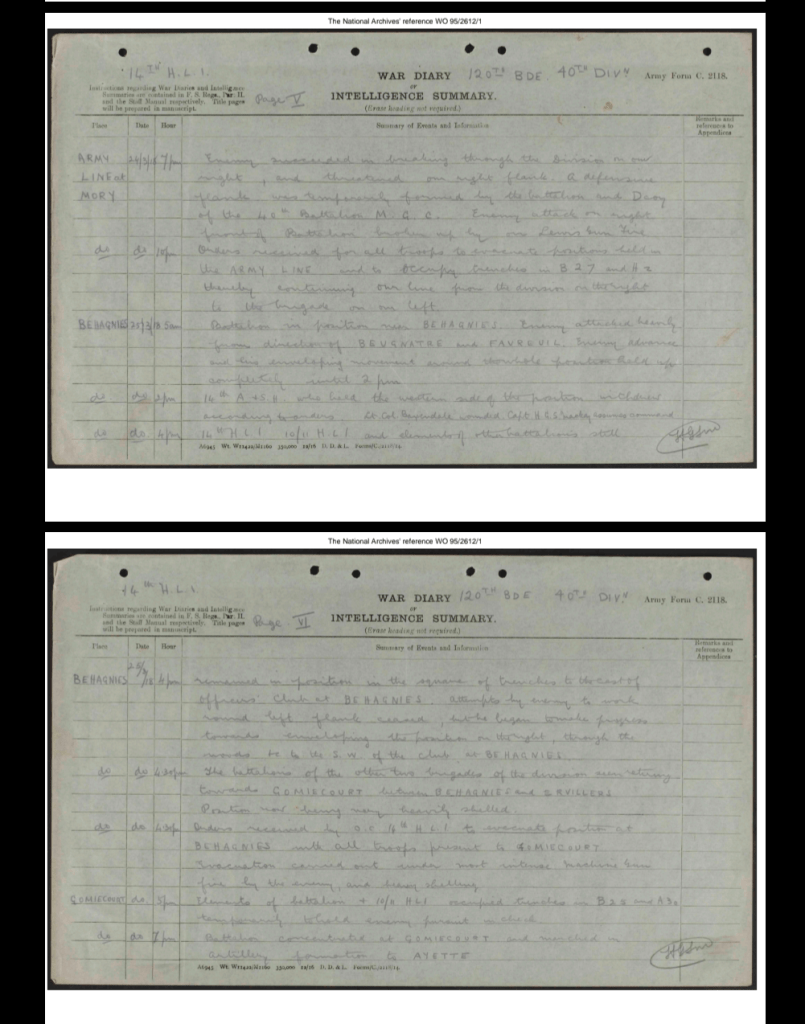

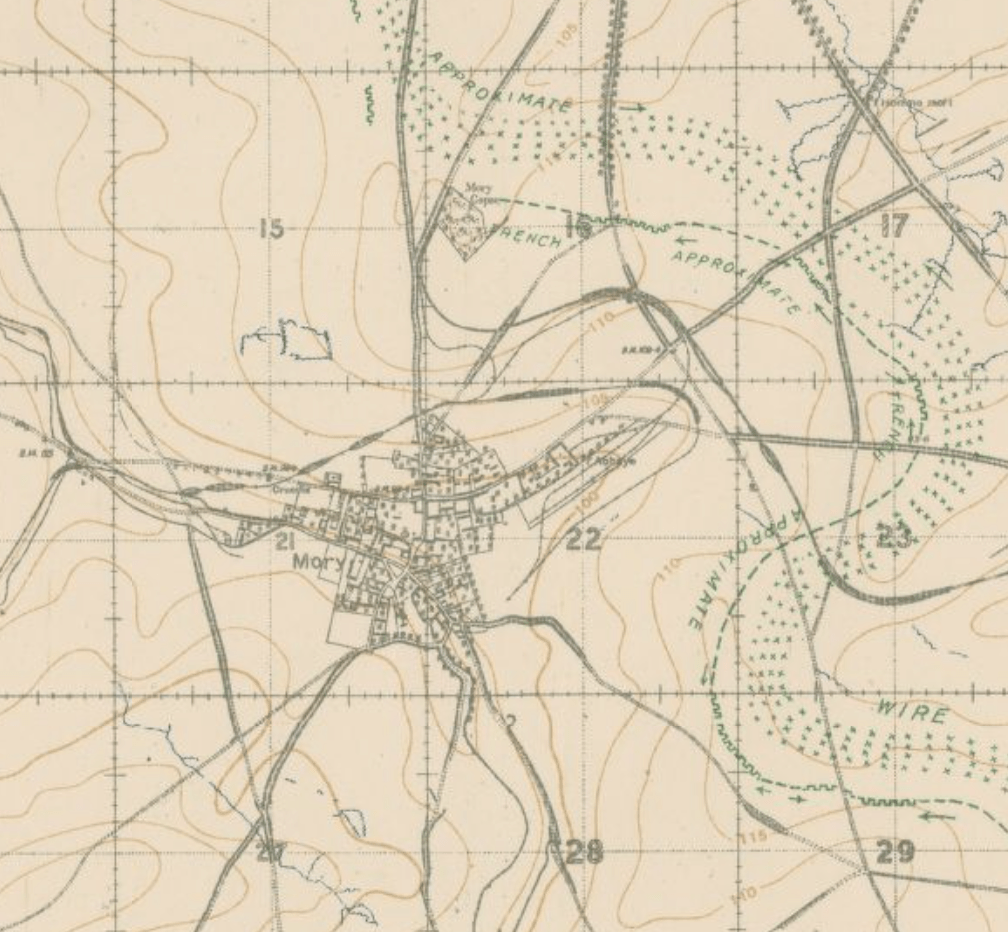

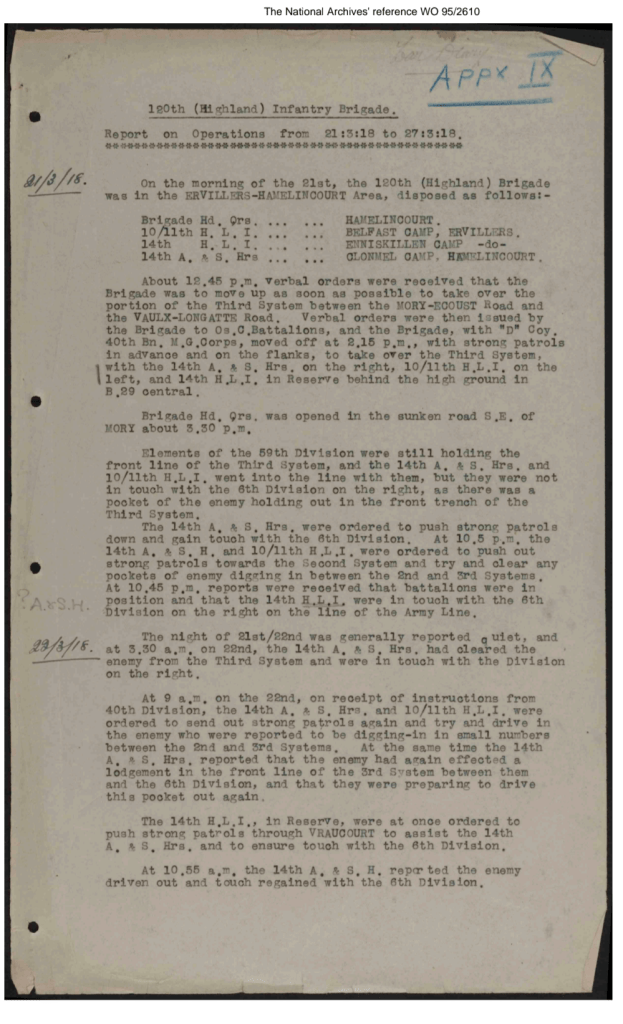

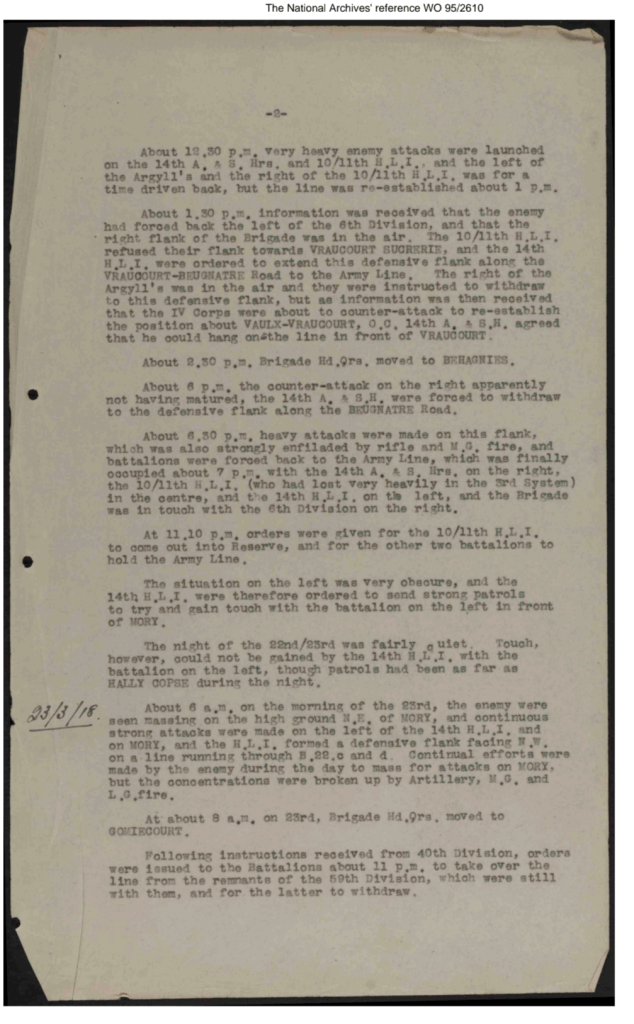

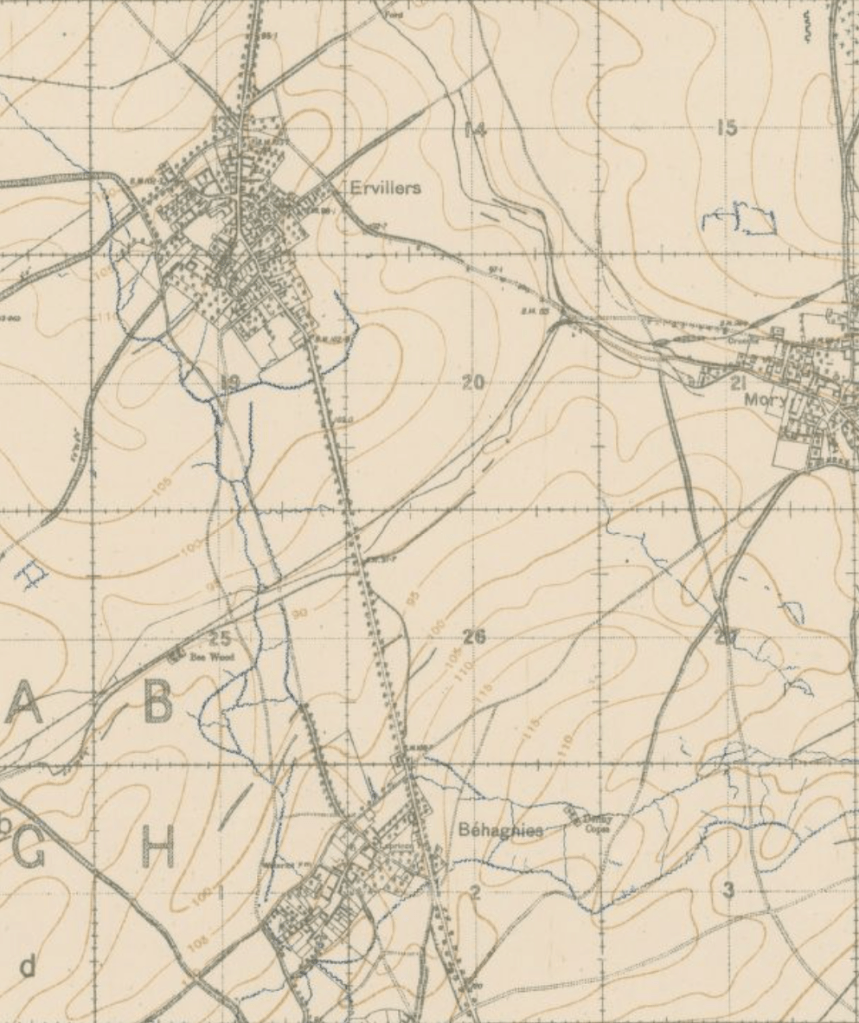

At the beginning of the German counter offensive known as ‘Operation Michael’ in March 1918, the 14th HLI found themselves near Mory, north of Bapaume. On March 25th they were falling back from Mory towards Béhagnies and Ayette. Almost overrun, with the line collapsing on their right and in retreat, it is during this period that Walter was taken prisoner. The war diaries suggest that the 14th had 124 ‘other ranks’ missing in that period, and the Brigade diary expanded that number to 466 men missing.

The 120th Brigade diary is perhaps best to gain an overview. WO95-2610 refers:

Walter appears in various missing reports, and also in German inventories for June and November 1918, showing him detained at Parchim on 26th June, and at Friedrichsfeld on 15th November at wars end.

The additional details are that he was attached to C company and fell into enemy hands at Beugny, which is further east on the Cambrai road than where they’d been fighting; so I suspect he was marched out behind enemy lines before being formally handed over to the German authorities. The records show a date of capture of 25th or 26th March. The German record also suggests Walter had an injury to his right arm – “G.G. Recht Arm” apparently translates as “gewehr geschoss” or rifle bullet right arm.

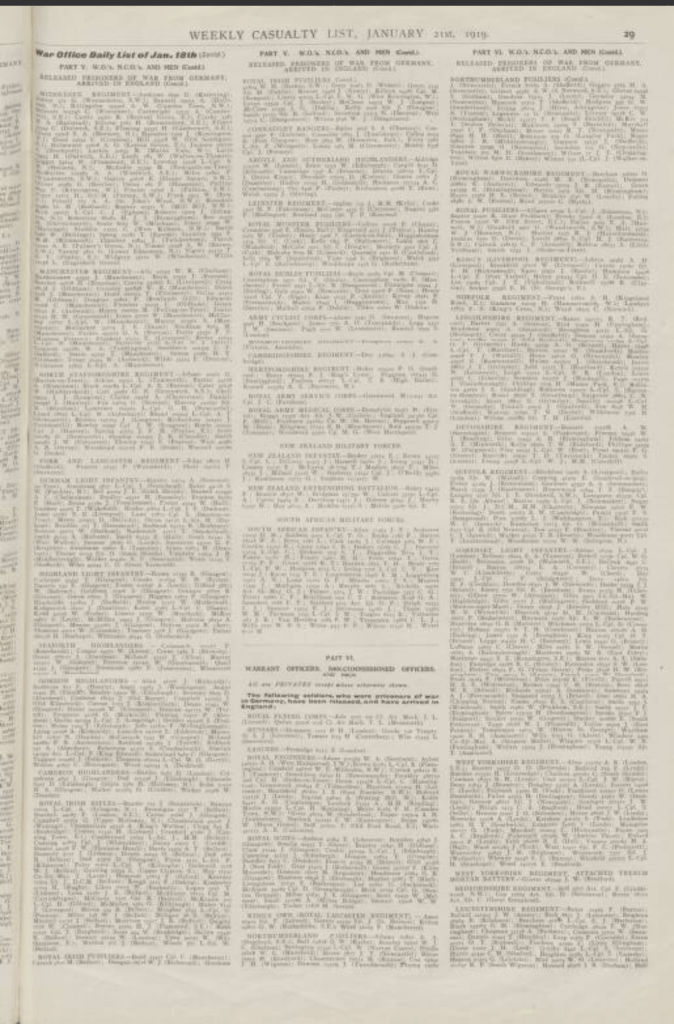

Records show that Walter finally returned from captivity to England on January 18th 1919.

I’m yet to study the war of the 14th Battalion in detail, but Chris Baker’s go-to ‘Long Long Trail’ records describes their movements as thus:

14th (Service) Battalion

Formed at Hamilton in July 1915 as a Bantam Battalion. Moved to Troon.

September 1915 : moved to Blackdown and came under command of 120th Brigade in 40th Division.

2 March 1916 : absorbed the 13th Bn, the Cameronians (Scottish Rifles).

June 1916 : landed in France.

Early 1917 : ceased to be a Bantam Bn.

6 May 1918 : reduced to cadre strength.

3 June 1918 : transferred to 34th Division.

17 June 1918 : transferred to 39th Division.

16 August 1918 : transferred to 197th Brigade in 66th (2nd East Lancashire) Division.

Their war diaries are held at WO95-2612-1. A project for another day.

At war’s end, Walter wasn’t finished and transferred his allegiances to the Coldstream Guards, attesting at Cupar, Fife on May 9th 1919, hence being on their medal rolls.

I don’t know when Walter left the army as I’ve yet to research him thoroughly, but he’s on the electoral rolls for Eccles from 1920 through to 1923, although he’s on the 1921 Census for the Foot Guards at Aldershot. It’s my belief he stayed in the army for some time.

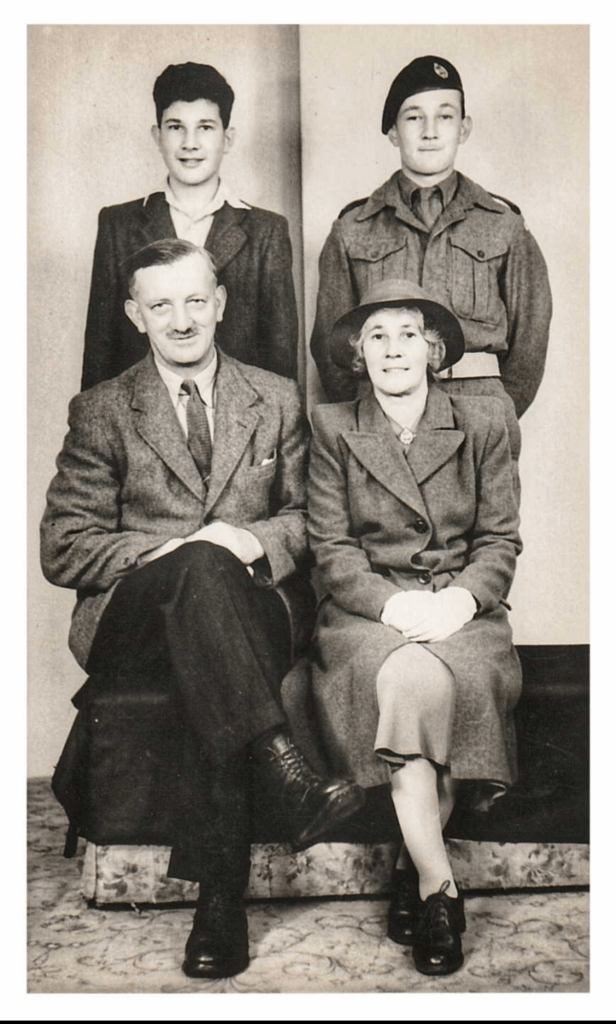

He was married to Jean Hobbs at Windsor in 1925, and his son Walter was born on Christmas Day 1929 and son John was born in June 1932.

By 1939, Walter was a sawyer and farm worker living at 7 Sawmill Cottages, Black Park, near Slough – Black Park being very close to Pinewood Studios.

Walter died on October 3rd 1949 aged just 51. Apparently I would have met his sons when I was small, and I vaguely remember meeting some of their offspring when they visited mum.

As with everything, with mum’s passing, the links to distant cousins who hold the keys to the knowledge about old soldiers like Walter are long since broken, so Walter will have to wait for another day until I get round to piecing together what he might have gone through in the Great War.

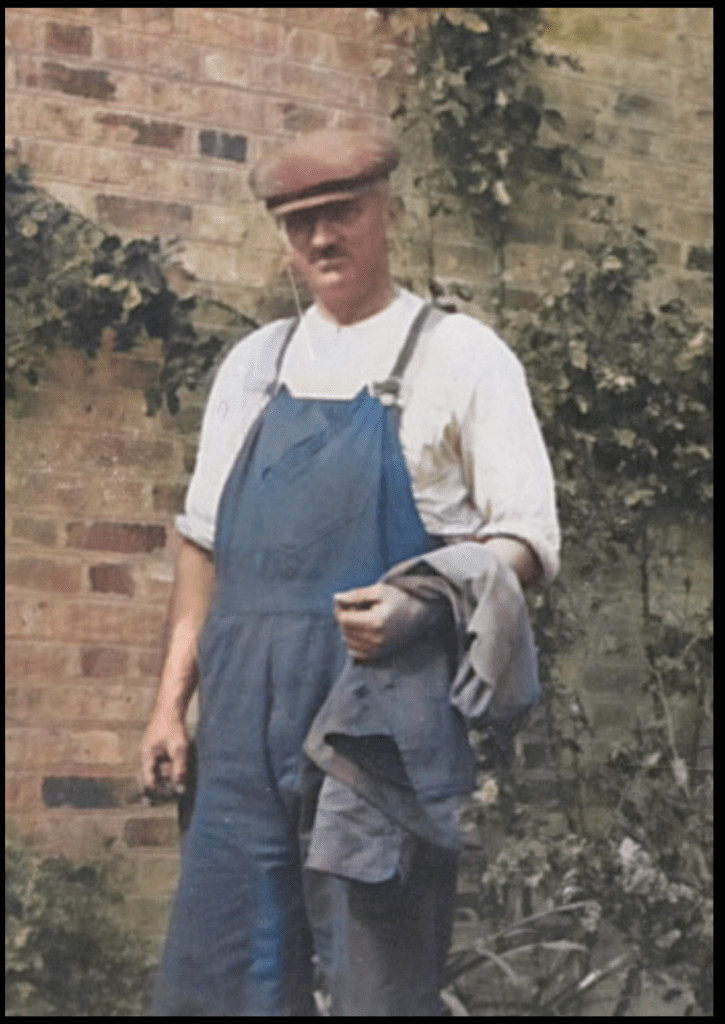

In the meantime, at least there’s a face to another who fought.