A tale of two brothers in wartime Norfolk

My daily walk to work takes me into the historic town centre of King’s Lynn; past the merchants houses of Nelson Street and the grand buildings of St Margaret’s Place opposite The Minster. Amongst the architecture is St Margaret’s House (now known as Hanse House), the modern facade to the medieval Hanseatic steelyard, but which at various times in recent history has been council offices, tea rooms, and a place to get married. For a good part of my working life it was a place in which the Coroner would hold inquests into death and tragedy occurring in west Norfolk.

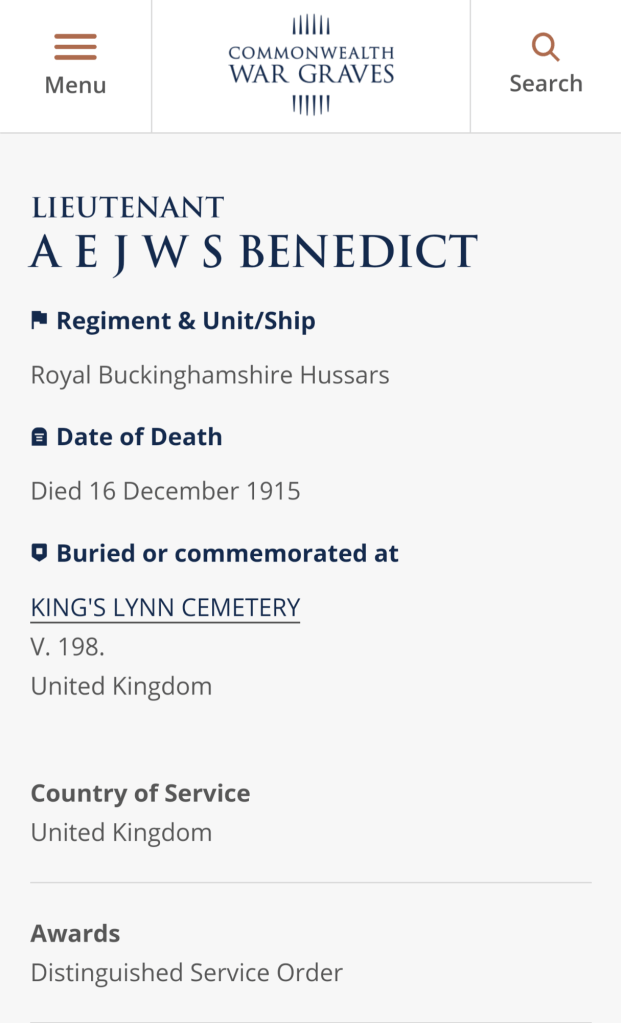

Although I have no idea how many lives were formalised into a neat verdict within its walls, St Margaret’s House plays a part in a sad tale of its own – of brothers caught up in the Great War. It’s a story I first came across in my role as a volunteer for the Commonwealth War Graves Commission while researching some of the men buried in the cemeteries of King’s Lynn.

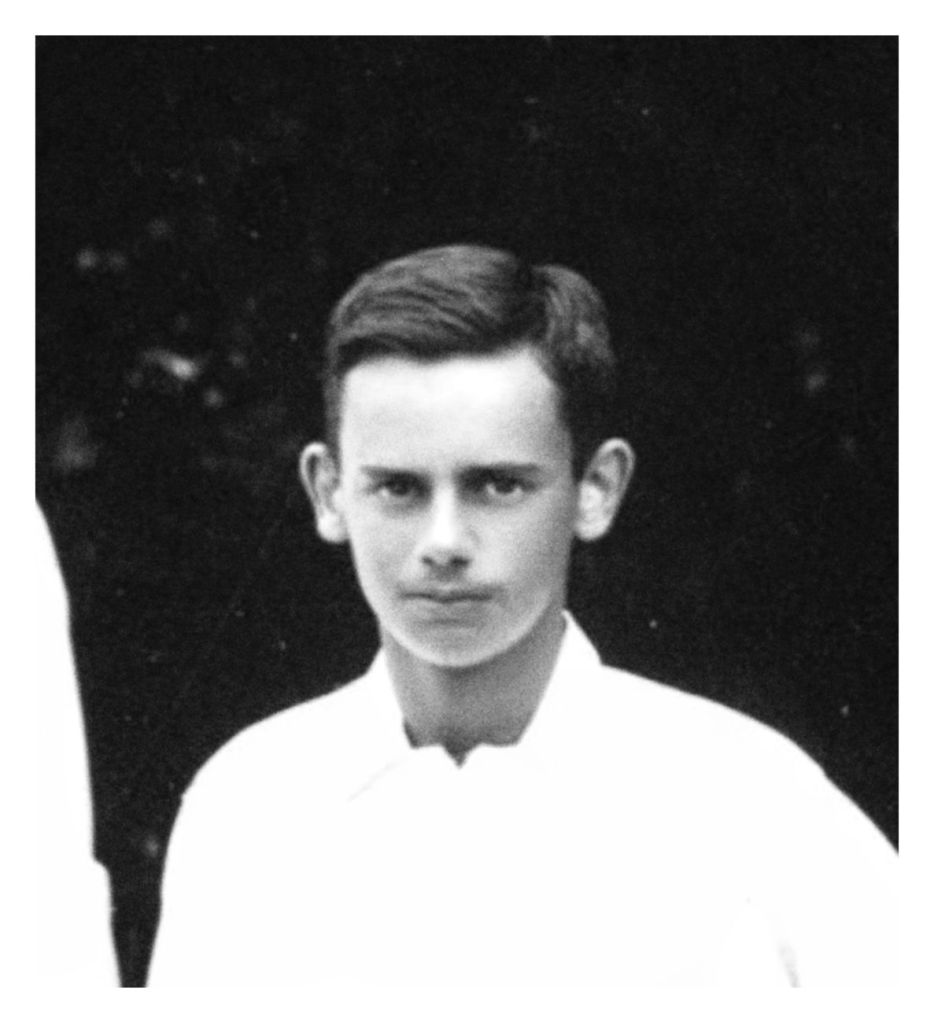

One of those men is Albert Edward Julius Wilbraham Scott Benedict (pictured above), who lies buried at Hardwick Road Cemetery.

Albert’s story is one of those that raises more questions than answers, and led me to discover a much sadder tale than just his alone.

But first a ‘brief’ biography….

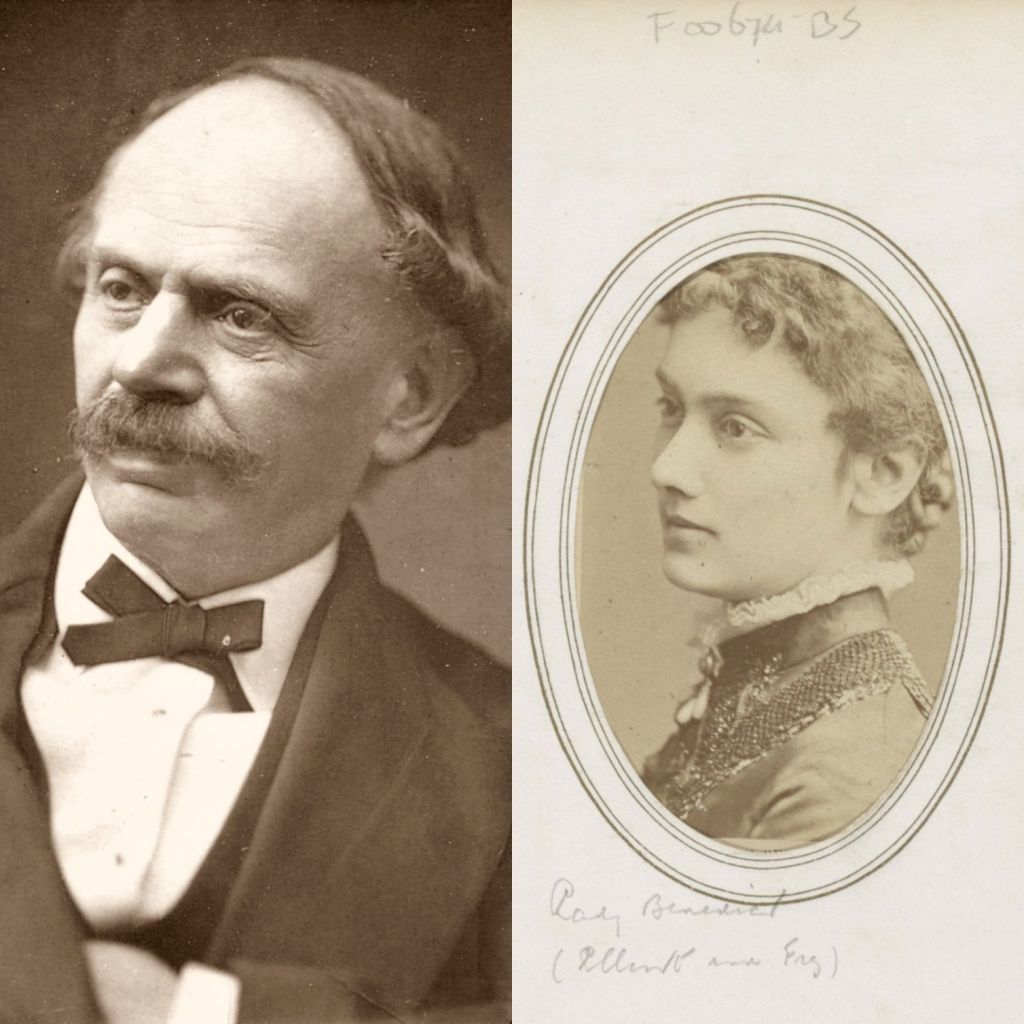

Albert was the son of celebrated German composer Sir Julian Benedict (1804) and his second wife, Mary Comber Fortey. Julian Benedict had found royal patronage in 1863 when tasked with composing the wedding march for Albert Edward, Prince of Wales and Princess Alexandra of Denmark. Mary was a piano student of Julian Benedict, and a musical artiste in her own right.

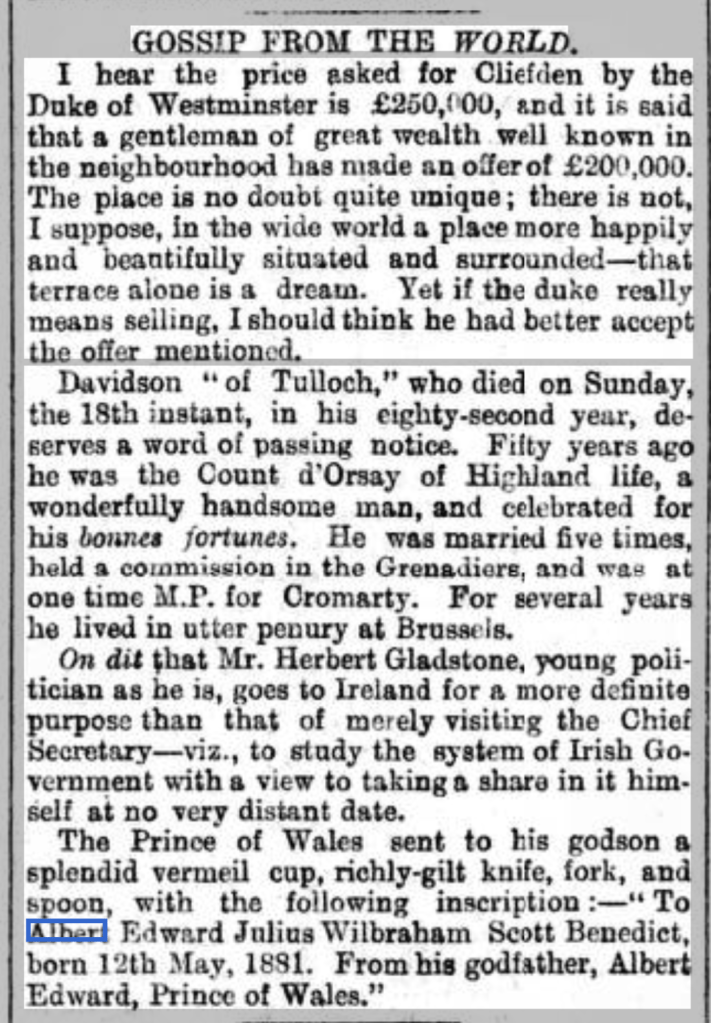

The widowed Sir Julian was no less than 53 years older than Lady Mary when they married in December 1879, but it seems age was no barrier to starting a new family when Albert was born on 12th May 1881.

It’s clear that young Albert was born into a privileged lifestyle of music and theatre, and the royal connection continued when the gossip columns lit up with news of the gifts from his godfather named as none other than the Prince of Wales himself.

Despite his good fortune, Sir Julian would himself pass in 1885 aged 80, leaving Lady Mary to raise Albert alone.

Things moved quickly though, and by February 1886 Lady Mary had married one Frank Lawson, a gentleman and cousin to Sir Edward Levy-Lawson, 1st Baron Burnham, proprietor and editor of The Daily Telegraph. Three younger step-brothers would soon join Albert as a result of his mothers remarriage: Lionel (d1887) Lionel (1889) Frank (1892) and Reginald (1895). Lionel would die young in 1903, and Lady Mary by 1911.

Albert would go on to be educated at Weymouth, then Winchester before going up to Oriel College at Oxford, graduating in 1902. He would inevitably turn to the arts and become an actor specialising in comedy roles. I’m sure the dashing Albert with his family connections led a grand life in Edwardian London with his godfather by now King.

However, the death of innocence was on the horizon. A relative of his step father was William Arnold Webster Levy-Lawson DSO, a pre-war Colonel in the Buckinghamshire Yeomanry and eventually the 3rd Baron Burnham, so it seems clear that this was a strong influence on Albert and Frank turning to the military on the outbreak of war in 1914.

Albert would be commissioned into the 2/1st Royal Buckinghamshire Hussars, with his relative in command. By spring of 1915 the battalion, along with now adjutant Lt Albert Benedict, would find itself billeted on coastal defence in and around King’s Lynn.

However, before we continue with the story of Albert, it’s crucial for context that we skip backwards to 1914 and to discuss Albert’s younger step-brother Frank Lawson.

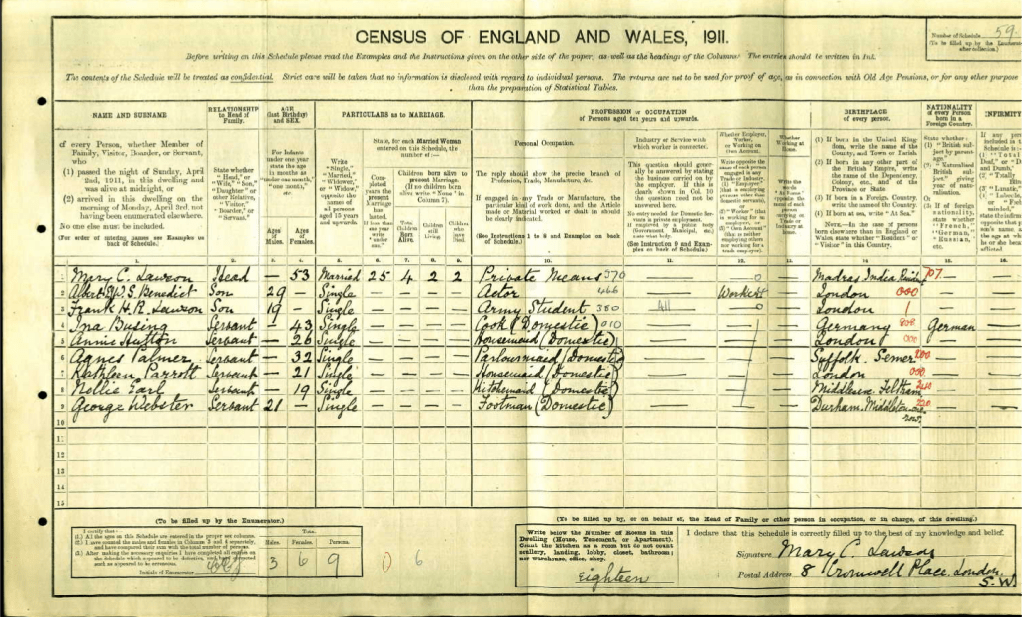

Frank Harry Reginald Lawson was a decade younger than Albert, born on January 1st 1892 at the family home at Hanover Square. I know nothing of Frank’s education, but he is listed in the 1911 census aged 19 as an ‘army student’ living with his mother and actor Albert and household at 8 Cromwell Place, London.

It would appear from the census record that a military career was already mapped out for Frank, due to the strong influences in his family, and it should be of no surprise that on the outbreak of war he was soon to be commissioned, again to the Royal Buckinghamshire Hussars – his London Gazette entry gives his date of joining as 27th October 1914, a couple of months before Albert would join the same family regiment.

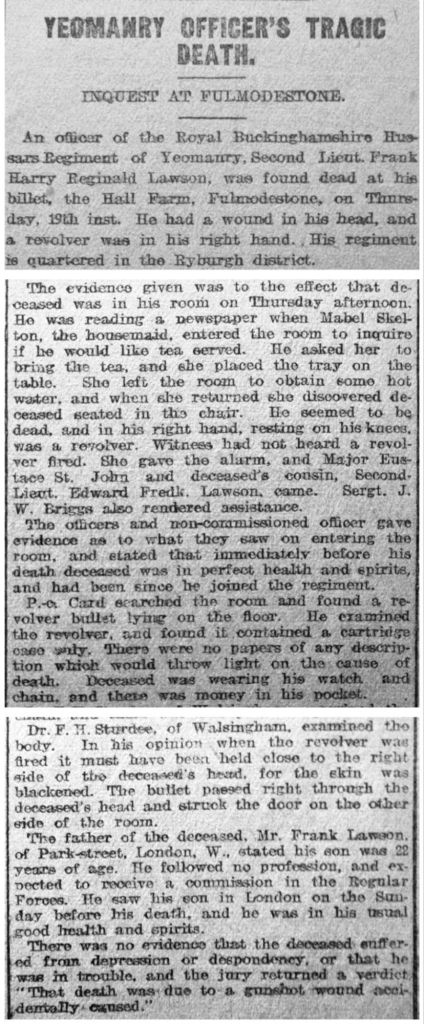

Like Albert, Frank would quickly find himself in Norfolk. With the battalion encamped near Great Ryburgh, Frank would find himself billeted at Hall Farm on Stibbard Road at Fulmodestone. What transpired next is something of a mystery, because within the month, Frank was dead.

The simplest description of the events of November 19th 1914 is contained in the article published in the Fakenham & Dereham Times dated 8th December:

The Buckinghamshire Free Advertiser and Press article of 28th November added a slightly different slant in suggesting an experiment with new ammunition, but in spite of the inquest reaching a prompt conclusion of ‘accidental death’, quite how an apparently happy 22 year old with a military background might find himself in difficulties with a service revolver loaded with a single round, pressed against his temple, isn’t easily explained.

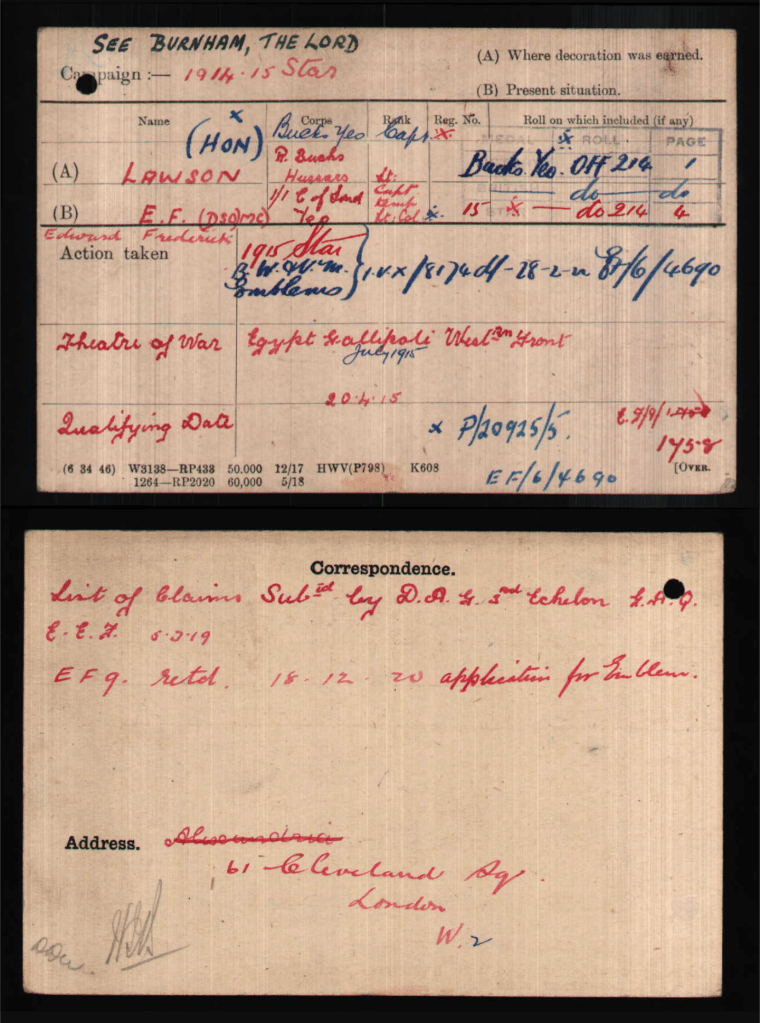

From the report it shows yet another family connection in that Frank was attended by his cousin, 2nd Lt Edward Frank Lawson, who would go on to become (you guessed it!) 4th Lord Burnham. The family connections were strong, and with the Lawson’s being newspaper people, I am left wondering what influence this had on the following proceedings. I have produced the Medal Index Card of Lord Burnham below. He would soon be off to a distinguished career as a soldier.

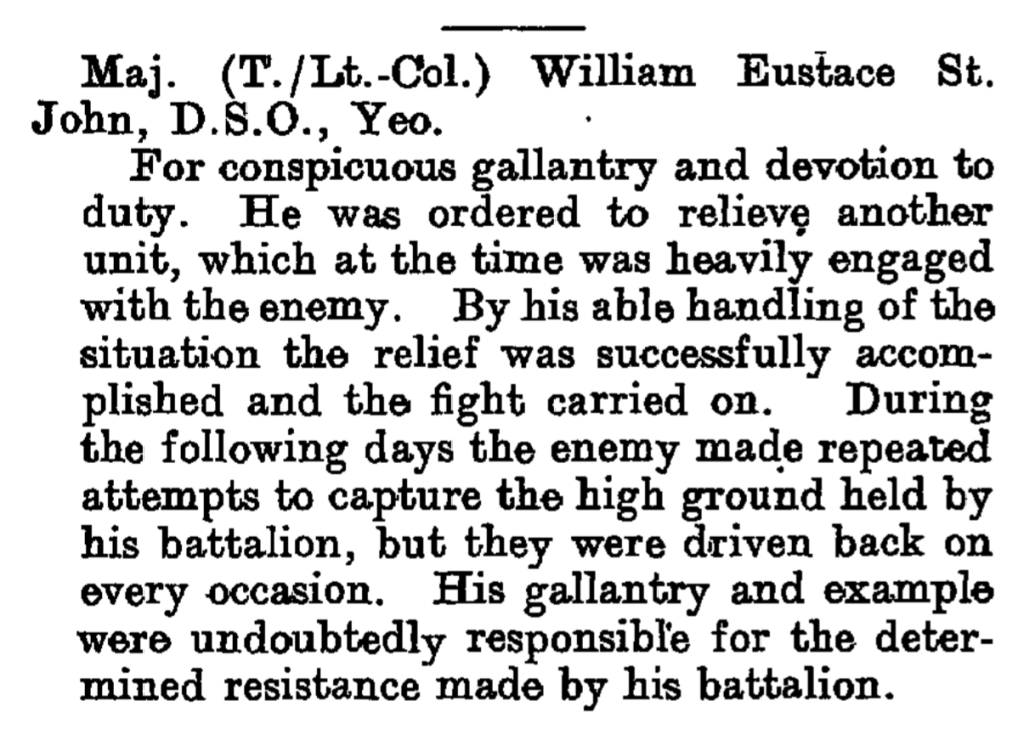

The other senior rank present was Major Eustace St John D.S.O. He too would know what a family reputation meant, and again went on to a distinguished career with the Royal Warwickshire Regiment – the regiment of Bernard Montgomery.

However, I digress, and return to the story of the step brothers Albert and Frank.

Frank was buried in the family plot at Kensal Green in London, with Albert continuing his duties with the Bucks Hussars as an adjutant. As a man in his 30s he would have been slightly older than many of the young officers around him, and the day to day routines would have consisted of maintaining readiness of the anti-invasion force and Zeppelin watches.

King’s Lynn had been the victim of a famous Zeppelin raid in January 1915, and the yeomanry tasked with guarding the town and port left their mark by carving their names in the brickwork crenellations of the town library on St James Road. I wonder if Albert had joined them on the roof as they watched and listened for raiders.

Continuing the story forward to 12 months after the death of Frank, we find ourselves back at St Margaret’s House in King’s Lynn where Albert Benedict had a room.

The events of the small hours of Thursday 16th December 1915 are again spelled out with perfunctory straightforwardness.

A young man; a bright happy sort of chap from a good family, ended his life by accident at his own hand from a single revolver shot in the place where he was billeted, aged 34.

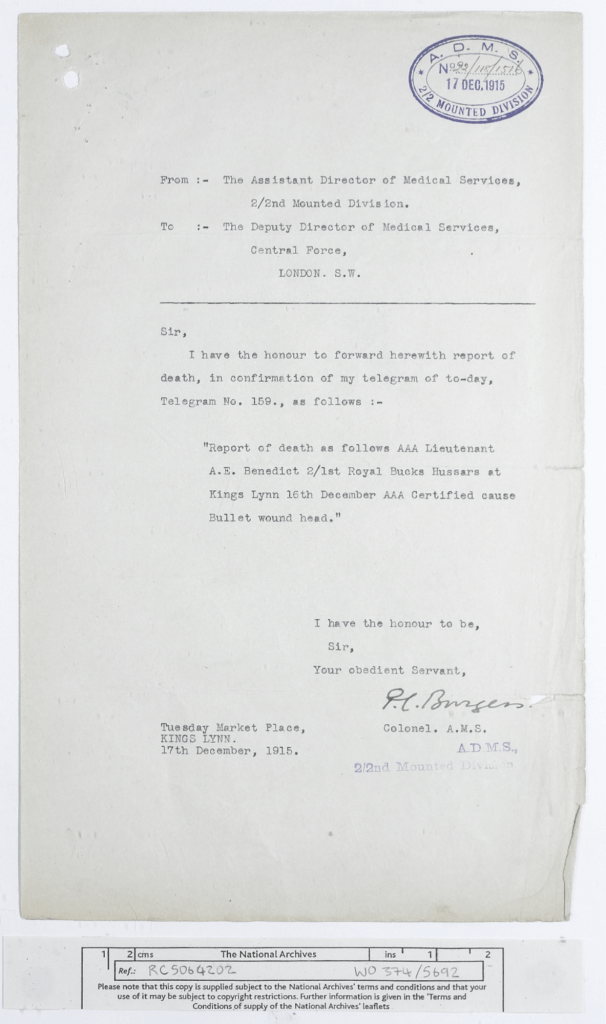

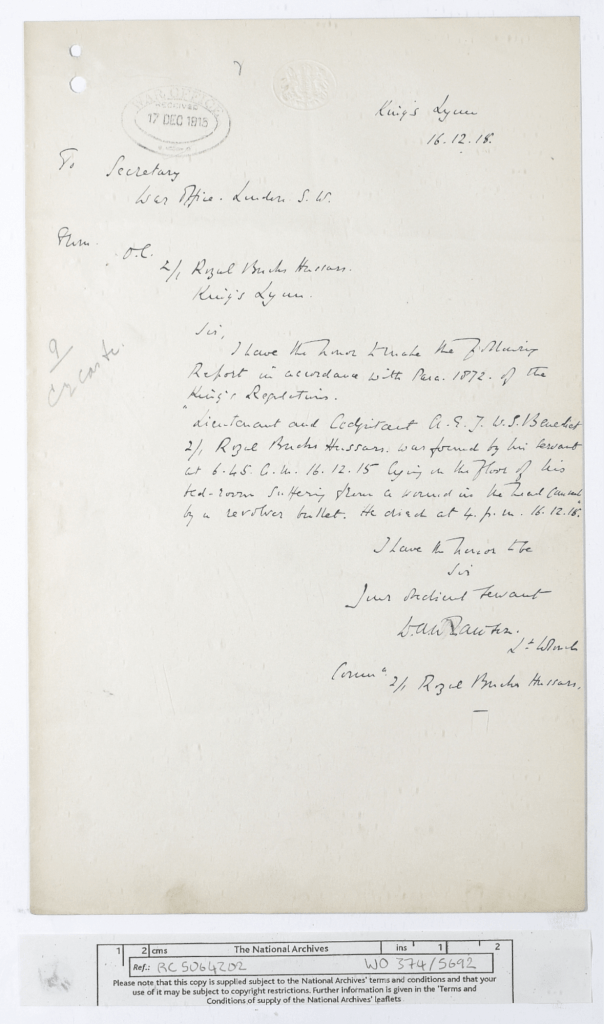

“Lieutenant & Adjutant A E J W S Benedict 2/1 Royal Bucks Hussars was found by his servant at 6.45am 16.12.15 lying on the floor of his bed-room suffering from a wound in the head caused by a revolver bullet. He died at 4pm 16.12.15” (letter to the War Office from Lt. Colonel Lawson). At the Coroner’s inquest he was stated to have been universally popular, that he “enjoyed soldiering” and had no debts worthy of note. A verdict of accidental death was returned and he was buried with military honours at Hardwick Road Cemetery, King’s Lynn, Norfolk on the 18 December 1915. His will left £9,618 18s 1d to his half-brother Reginald Lawrence Lawson, who also received his medals.

For context, a quick internet search suggests that an estate valued at £9,600 in 1915 gives a purchasing power of £1.2 million in today’s value.

The Downham Market Gazette of Christmas Day 1915 reported the following:

When I first researched Albert Benedict a few years ago, any report of a man dying at his own hand be it by accident or otherwise, comes as a shock. I can only imagine what story lies behind the facts presented to the public through the inquest and newspaper article.

It brings it closer to home as I work in the Town Hall, and although that lovely ancient building has witnessed the ebb and flow of life for hundreds of years, this sad tale has stayed with me. I can only imagine what the truth might have been for a young man, or why those with influence might be so quick to draw a veil over a tragedy. We can only speculate on the state of mind of young soldiers a century ago, especially ones bereaved of a younger brother just months before. We will never know.

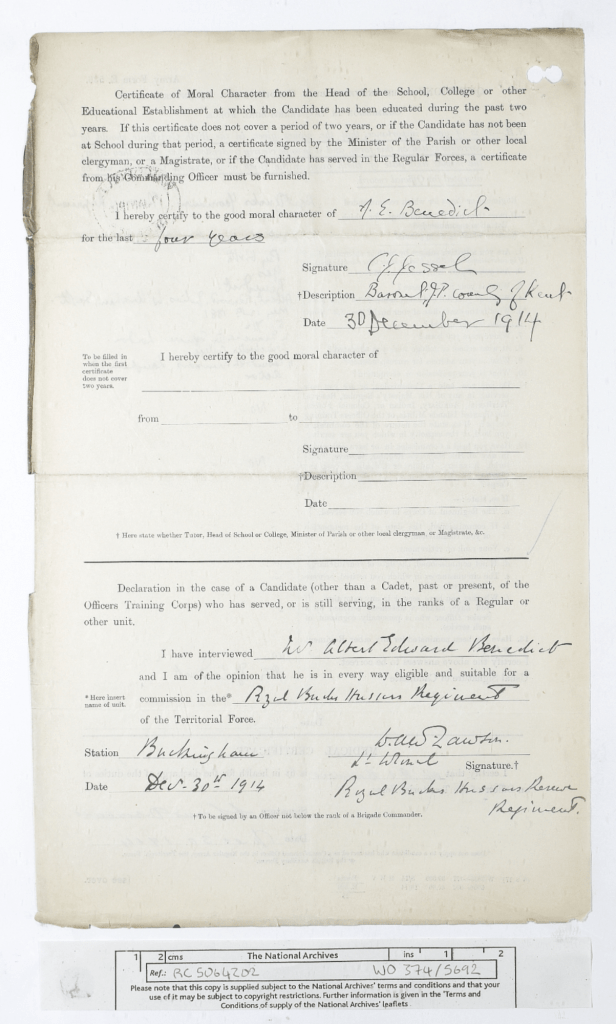

I had hoped that there might be further clues in the National Archives, where a file of Albert’s personal papers is held. Unfortunately, they contain only the humdrum business of settlement of Albert’s affairs, although it is poignant that the papers included both his commission documents and death report, both signed off by W.A.W.Lawson – the relative and commanding officer so keen for Albert to be a soldier in the family regiment – and perhaps the man most saddened and embarrassed by two young men of his family ending their lives by self inflicted gunshots while in his charge.

Some of the National Archive papers are below (WO374/5692):

As always, soldiers effects and affairs are just dusty files held in archives, telling us nothing and everything about how they lived and died. With Albert and Frank there is so much more than is contained in the historical records.

Undoubtedly this was a sad chapter for one branch of high society with links to the royal family and press moguls. No doubt that society has changed over the century since two young men passed, and that attitudes are different allowing the truth to be discussed more openly. I leave you to read between the lines for a motive as to why a single man in his 30s and with a background that is the polar opposite to military life, might arrive home at midnight and have an ‘accident’ with a gun a short time later.

By happenstance I spent last weekend in Fulmodestone just around the corner from Hall Farm where Frank’s short life ended, and being equally stumped for a motive, this prompted me to get on with sharing my thoughts on the life of him and his older brother. So here we have their sad tale.

Casualties of war take many forms, and although Albert and Frank have stories that are hidden deeper than most, I will remember them as I walk to work along the cobbled streets of old Lynn on my way to the office. As previously stated, Frank is buried in the family plot in London, while Albert is buried at Hardwick Road in Lynn. Was he a black sheep, deemed unworthy of burial near his brother? A final mystery is that the Commonwealth War Graves entry for Albert attributes a Distinguished Service Order to him. In spite of his noble connections, and unsurprisingly due to his very short home military service, I can find no record to support the award of the DSO to him.

The image of Albert Benedict is copyright of Winchester School.