Uncle Syd was one of the key people in my fledgling interest in the Great War, as he was the one of my grandfather’s brothers with the most tangible connection to the Western Front when I began rummaging in the memory of my mother’s history.

From the point many years ago when I first began to contemplate my family, he was a focal point, and the first relative buried on a battlefield that I visited when I travelled to Belgium 15 or more years ago; and I believe I was the first relative to make the pilgrimage to his burial place.

Also, I realised that since I’ve written about all those old names, Syd has been mentioned a number of times in the wider tales but never received a blog dedicated just to him. He’s even become popular amongst my friends Paul & Steve who often drop by his headstone when they visit his burial place. A recent visit to hear Sir Michael Palin talk about his great uncle Harry, and an impending trip to the battlefields has given me the nudge I needed.

Early Days

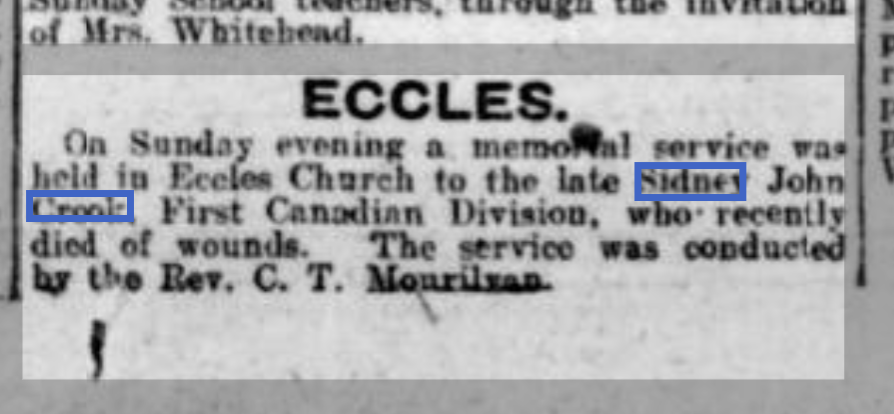

You’ll have to read my other blogs for a recap of the family tree, but Sydney John Crook was born on March 2nd 1892 at East Harling; the third child of eleven children to Harry and Mary Crook. I spell his name with a ‘y’ because although pretty much every written record you’ll see about him (including much of what I’ve written about him!) calls him ‘Sidney’, it’s Sydney that his father had inscribed on the family plot. As you’ll also see later ‘Syd’ is the name he wrote on his last will and testament.

The family were farm workers – Harry was foreman at Overa Farm at Eccles near Attleborough; and Sydney worked on the land as a labourer.

Harry had been a pre-war soldier serving in Egypt with the Royal Artillery in the 1880s, and the oldest sons Edward and Harry Jr had followed his example by also joining the R.A as soon as they were old enough, but Sydney took a different path initially.

To Canada

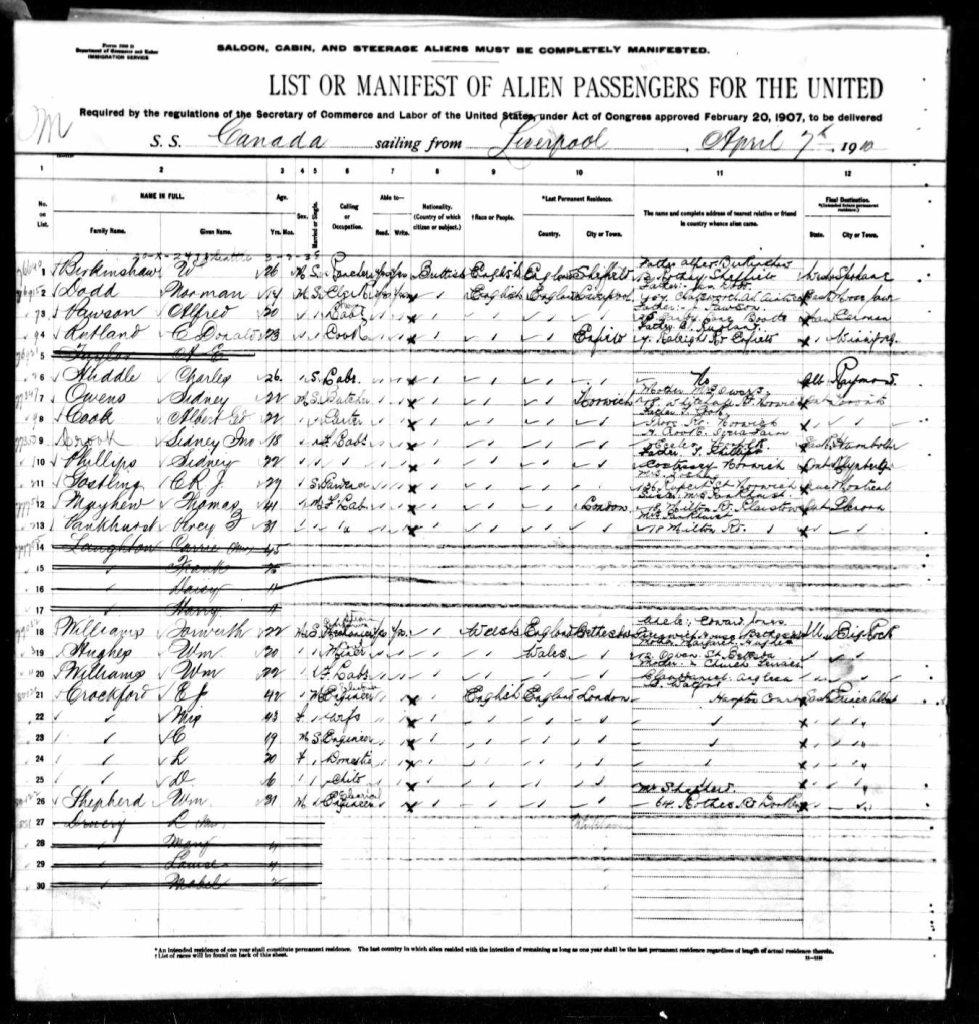

Sydney was 18 years older than my grandfather. By the time my grandfather was born in October 1910, Sydney was on his way to Saskatchewan as a farmsteader, following the lure of the Dominions Lands Act and the offer of the chance to strike out on his own. He sailed to Portland, Maine from Liverpool on 7th April 1910 arriving on 16th April. His occupation was given as ‘farm labourer’ and his destination Humboldt Saskatchewan. His religion was given as ‘non conformist.’

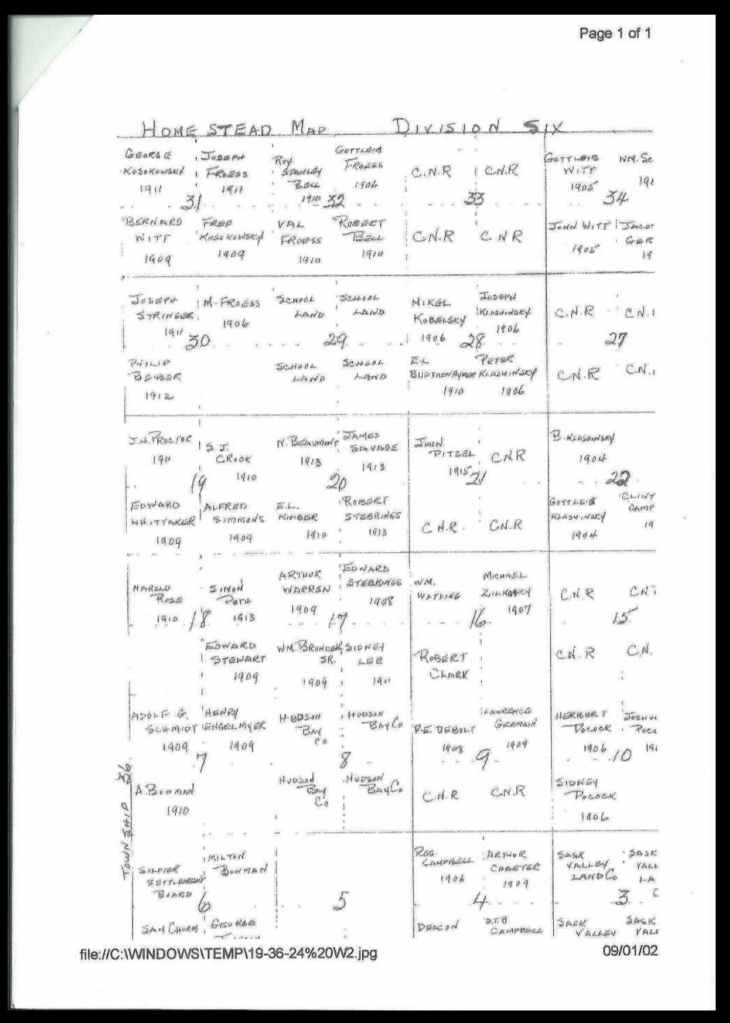

We know that Sydney was eventually allocated a division of 160 acres at Township 36, section 19, which I believe is at Mancroft. He was given the responsibility of clearing it and building himself a house (albeit little more than a shack in the woods). I presume he initially laboured for other homesteaders while he waited for his own grant of land to be approved.

The above map and Homestead register shows Canada was divided up into a myriad of 160 acre squares, each allocated potentially to a single individual who had travelled from across the empire and Europe to start new lives. I know from the family tree, that family descendants from Norfolk eventually married Norwegians such was the diversity of the pioneer farmers that cleared the plains of central Canada.

One of the great mysteries of the Crook story is why Sydney ended up in the extremely remote township of Mancroft. We have no record of how his destination was chosen, but if you look at the burial records for the tiny church there, you will see successive generations of a Crook family are buried there.

This family seems to have its roots in Ontario, but apparently comes from the line of Richard Crook who originated from Somerset. Maybe they were distant relatives? We simply don’t know the answer.

We have no information whether Sydney formed a relationship in Canada, but you can see that he was finally allocated his own section on January 26th 1914, just months before the outbreak of war.

We know that on 9th October 1913 his next older brother Harry Jr. had arrived in Quebec on his way to join Sydney at Humboldt, having just left the Army. Harry at that point had clearly decided that his future lay in Canada too. So much was about to change….

We’re not certain which one of the brothers is in the picture above, but it gives some idea of what life was like in Saskatchewan in the early 20th century.

The Call of King and Empire

Although we don’t know too much about life in Canada, we can surmise that life was tough in the winter of 1913, as Saskatchewan can be a frozen snowscape from late October until spring.

One certainty is that on the outbreak of war in August 1914, Harry, as an experienced soldier of 6 years service, enlisted immediately with the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry.

We assume that Sydney was then in something of a dilemma, having to decide to leave his farm home of some 4 years and answer the call of King and Empire. I don’t know of what arrangements he put in place to manage his land, but I can imagine that as a single man of 22 and coming from a family of soldiers he undoubtedly felt compelled to sign up. We don’t know if he had any misgivings, but on 21st December 1914 Sydney attested at Saskatoon as Private A/40009.

He would soon be on his way back to the homeland.

To England and To War

As with all Canadian soldiers of the Great War, we are blessed with archives that contain individual personnel files that give us a great insight into the fighting men who took up arms.

22 year old Sydney was 5’10” with dark hair, a fresh complexion and blue eyes. He was slim weighing 175lbs with a 38″ chest and a scar between his eyes.

You will have to conjure your own picture of him, as sadly the family has none that is definitely of him, but I imagine a young man toughened by a hard life grown from the stony soils of south Norfolk, and honed by the harshness of a new life forged by four iron-cold winters in Canada.

Maybe the picture above includes Sydney? The man standing in the rear centre bears a strong family resemblance. The man front left could be Harry.

‘Team Shield Winners 1913’ narrows the possibility of it being both brothers to after October 1913 when Harry arrived, but would he have had time to win a shooting prize before the end of the year? We know that Syd clearly had shooting ability because his service file tells us he was selected for sniper training.

There’s no other reason for the picture to be in the family collection if it’s not one of the Crook boys, which relatives believe it is. If it’s earlier in the year it can only be Syd as he was the only brother in Canada.

I don’t propose to lay out Syd’s course to the Western Front in great detail, suffice to say he went through the 32nd Battalion for basic training, finally drafted to England in June 1915. Sydney disembarked from the SS Scandinavian at Shorncliffe in Kent on June 27th 1915.

We can wonder if he had opportunity to get home to see his mother Mary, as there are tales of her joy as her boys arrived by train, but in truth we don’t know. It’s likely that this would have been his first opportunity to meet my grandfather who was by now a toddler and would only have heard talk of his older brother; July 1915 was the only chance I can imagine where he might be given a few days leave to travel to Norfolk from Kent.

We do know however that on August 3rd 1915 he was on his way to France with the Canadian Expeditionary Force, and by August 14th taken on strength of the 5th Battalion Canadian Infantry. He was joined by many men who may have followed a similar path in that a large percentage were British settlers to Saskatchewan drawn together to form the battalion.

Life and Death at the Front

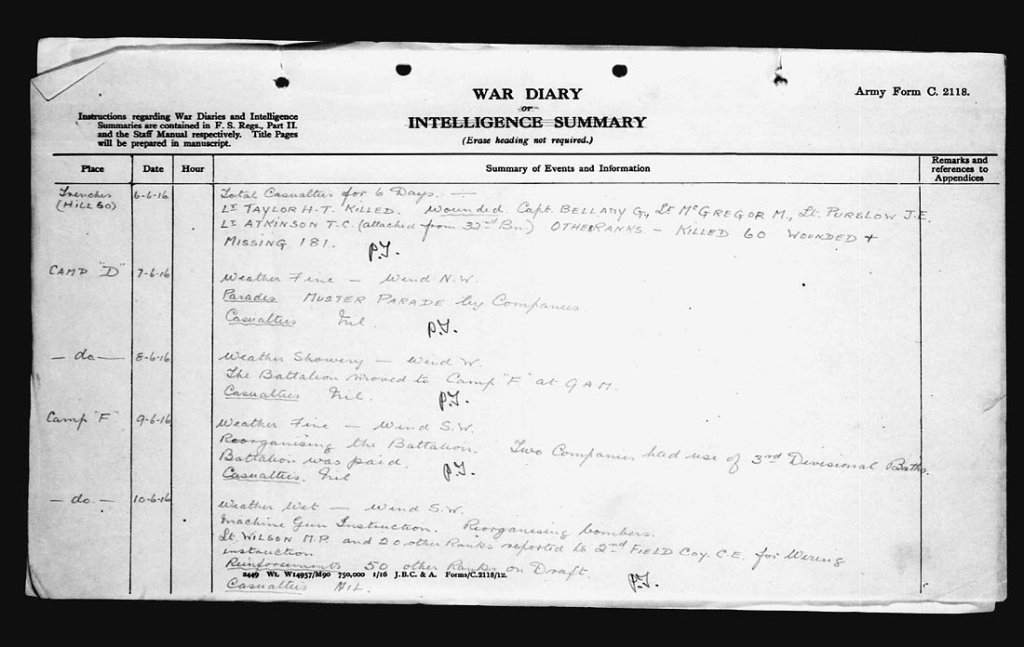

When you read the war diaries of the 5th Battalion, you will see that they are unfailingly neat and concise. The authors followed a precise edict to avoid giving away too much information about locations and when in the trenches invariably use grid references and trench numbers rather than place names. Equally, the prevailing weather is always described, giving colour to otherwise dour reports.

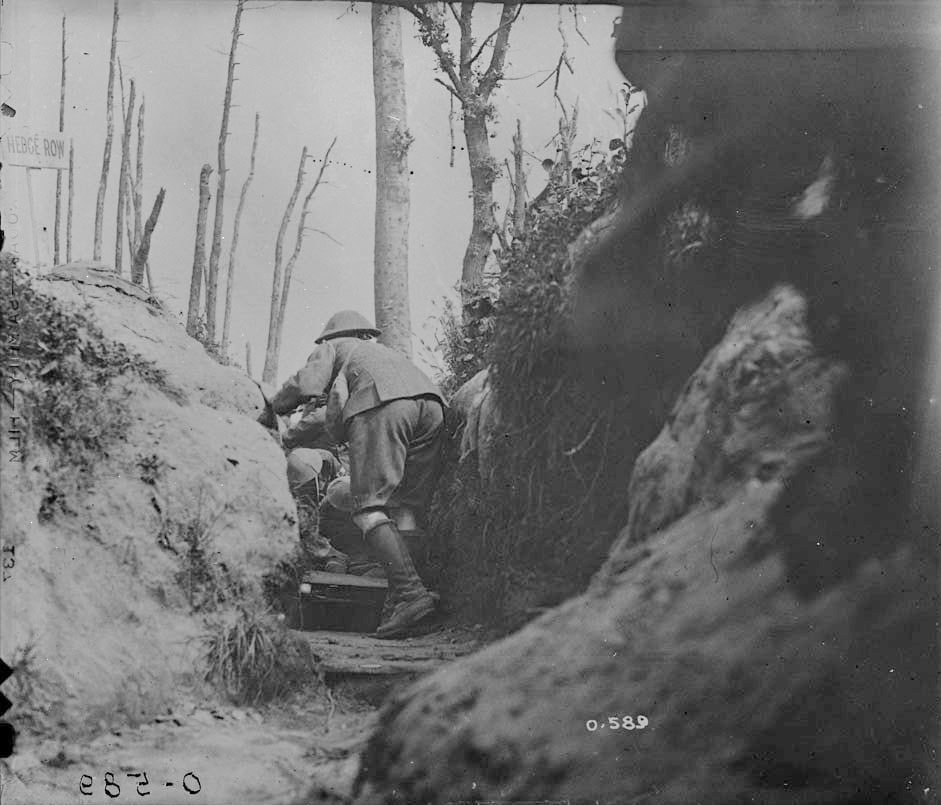

To precis their service at the front, the 5th spent most of their time from August 1915 until Sydney’s death in midsummer 1916 holding defensive positions in the southern Ypres salient. Like most Canadian units at that time, they were yet to be given complete responsibility to lead offensive operations, but none the less had gained considerable experience.

The 1st Canadian Division had seen plenty of action in the 2nd Battle of Ypres; places like St Julien, Festubert and Givenchy in the spring and early summer of 1915, but now was a more mundane period

Having glossed over Sydney’s war thus far, it is fair to say though that he suffered the full gamut of trench life – artillery bombardment and trench raids – all part of the cut and thrust from the end of the Loos engagements up to build up for the Somme offensive. He would have lost friends in the regular bombardments and been used to the hardships of soldiering.

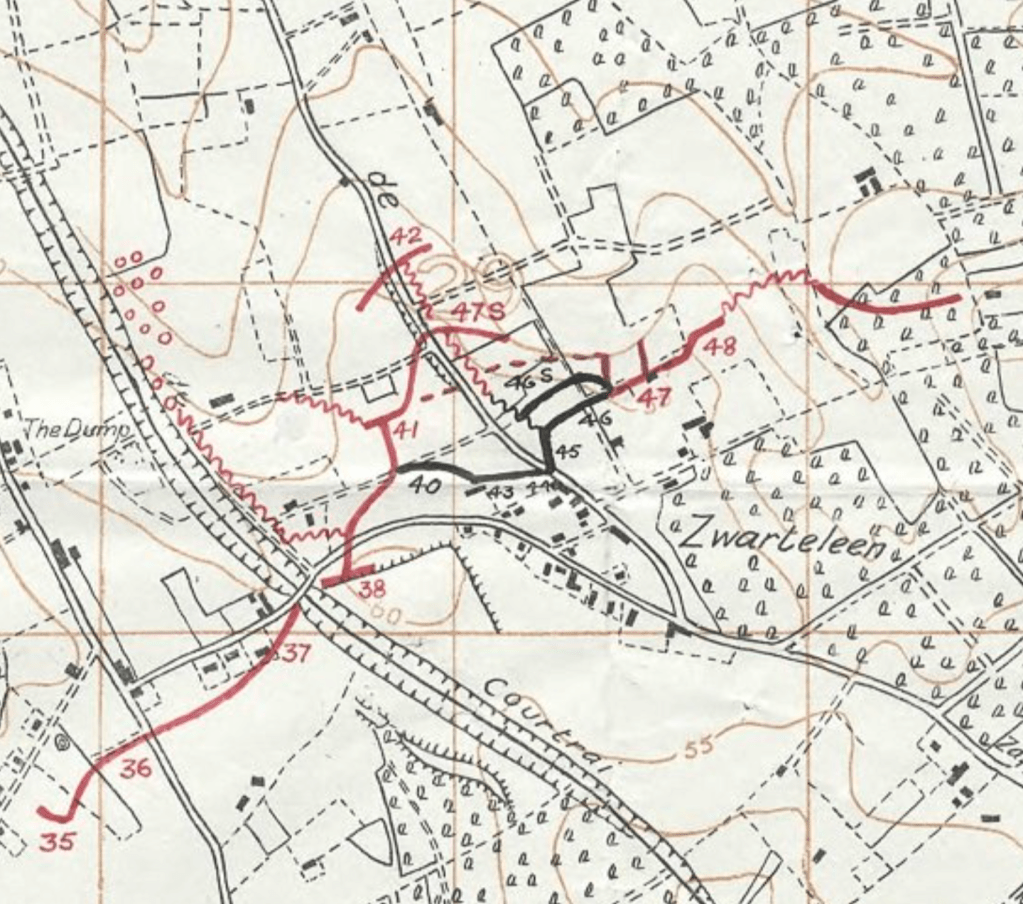

In the late spring of 1916 though, things would begin to change. Soon the 5th would move in April to the trenches in front of ‘Hill 60.’ This infamous piece of landscape had been a meat grinder since the retreat from Mons parked the front line there in 1914, and would continue to be a loggerhead until the end of the war; the 1939 – 45 war even saw fighting here.

Things were traditionally ‘hot’ here with both armies pushed up close together to within feet of each other, to within shouting and swearing distance. To give a summary of what life was like for Sydney and his comrades, below is a diary extract from 17th May in which Maj Gen Sir Arthur Currie writes to the battalion.

In those late spring days of 1916, the allies were focused on ramping up resources for the Somme offensive, planned for late June. Fully expectant of this, the German army sought to harass and occupy forces aligned around Ypres. The Wurttemberg divisions facing the Canadian brigades took it upon themselves to keep them fully occupied. It should be said that much of the highest ground of the salient was controlled by German positions, but that the high points from Hooge across to Hill 60 and the adjacent railway in the Canadian sector were under allied control.

There is a suggestion that a Wurttemberg commander took it upon himself to launch an offensive on June 2nd to redeem himself having been admonished for some perceived failure; the offensive became known as ‘The Battle of Mount Sorrell’ and focused on Hill 62 or Tor Top, and spread the width of the Canadian sector.

The End Game

Hill 60 would have been a miserable place to serve due to its proximity to the enemy and strategic value as a gateway to Ypres. Furthermore, Sydney had attended sniper school for a week in April, so you can imagine his value as a target to the enemy as he smuggled his rifle through a loophole looking for targets just yards or even feet away.

For family context, at the point the battle broke out, Harry Crook was just a short distance away in Sanctuary Wood with the PPCLI. As a coincidence, the brother of my paternal great grandmother, William Hinnells, was to the rear of Sydney with the 1st Canadian Field Ambulance. He too was an emigre to Canada from Norfolk.

In a long story cut short, the battle opened on June 2nd and raged continuously until the fateful day of June 6th and beyond.

The diary entries below show that Sydney and the 5th were in their positions directly in front of Hill 60 on June 6th when a trench mortar bombardment opened up at 9am and lasting until 1230, when artillery joined in until 4.30pm. A further bombardment occurred from 5.30pm until 6.15pm. Trenches 40-43 are described as being ‘practically destroyed.”

Although Sydney is buried in Flanders, he is marked at his local church of St Mary the Virgin at Eccles. When his mother Mary died in 1922, his name was added to her headstone, along with younger brother Herbert who lies in an unmarked grave in Mesopotamia. Mary, on hearing of Syd’s death, had had younger brother Walter removed to the reserves in the Lincolnshire Regiment as he had joined up under age.

It’s in those terrifying moments during the bombardments on June 6th that I believe Sydney was mortally wounded. For those of you who know Hill 60 today, that ground is behind where the houses and Hill 60 café stand opposite. Below are maps that give an idea of what the ground looked like.

We see from the personnel files that Syd was admitted to 10 Casualty Clearing Station at Remy Sidings (Lijssenthoek) on June 7th, where he died of ‘shrapnel wounds multiple.’

I know nothing of his evacuation journey to 10 CCS, but it has always intrigued me that William Hinnells and the 1st Canadian Field Ambulance could have been involved in carrying him on his final journey, long before their families were joined by marriage – part of the reason why Hill 60 and the ground from there across to Lijssenthoek is so sacred to me.

I wonder, too, if he was evacuated during the action of June 6th before his battalion was relieved at midnight, or if he was left where he fell to be found the next day. We have no time of admission to give more context to his last hours.

You can find maps and diagrams that show the routes back for the wounded, but it seems likely to me that the Regimental Aid Post at Larch Wood would have been the first port of call for the dying Sydney, then on a rail trolley to an Advanced Dressing Station at Railway Dugouts close to where the cemetery is today.

Whether carried on stretcher or wagon, it was probably then on to Vlamertinghe Mill Divisional Collecting Station, before finally the transfer to the Casualty Clearing Station at Lijssenthoek where men could be quickly entrained to the major hospitals on the coast.

In truth, we don’t know how long Syd lived after the bombardment, or whether there had ever been any realistic hope of his survival. All we have is those three perfunctory words repeated throughout his file: shrapnel wounds multiple. In any case, he was dead within the day.

I can only imagine….

That, sadly, is how it ended for the young farm boy from Norfolk – a far from unique experience.

There’s much more I could write about the intricacies of Sydney’s war, but I’ve covered so much in the other blogs you’ll find on this site, and it was him that gave rise to the title of this website.

I’m pleased though that others have shared my remembrances of him, and finally, I’ve got round to paying him an individual tribute by writing this short tale, and officially corrected the spelling of his birth name.

Farewell uncle Syd.

To Sydney John Crook

March 2nd 1892 – June 7th 1916