Umówilem sie z nia na dziewiata

“I have a date with her at nine

And just can’t wait to see her

I’ll ask the boss for an advance dime

And bring her a bouquet of flowers

Then the movies, a café and a walk

Through the moonlit night

And we’ll be happy and merry

‘Til at midnight we’ll say goodbye

And I’ll ask her out again

At nine like today“

Emanuel Schlechter

Words from a 1937 Polish musical comedy “Piētro Wyzej” (Upstairs) written in a time when dark clouds gathered in an uncertain Europe. Poland of the 1930’s would prove again to be a pivot in history, as it had been across the ages, positioned between the competing powers of East and West. It’s here I drew my inspiration for another blog about a young man whose journey is remarkable but yet so familiar. This one, however, is a departure from my usual preference for family related sources; but having said that, the story ends with a local Norfolk connection. The beginning of all this though is rather abstract. Someone I follow on Twitter through a policing context had mentioned that she had an uncle who’d been a Polish pilot in World War II. That’s how it works: Cate had been responding to some ‘Brexity’ conversation about the true meaning of patriotism, and that we’re less divided than we all realise. She mentioned ‘Uncle Stan’ and Douglas Bader. I was just browsing by. Uncle Stan. Douglas Bader. I was intrigued.

Bader is a legend in wartime aviation history. A couple of questions revealed Cate knew Uncle Stan as ‘Stan Breski’ and had very fond memories of him from her childhood, but all anecdotal and without detail. And that’s where this story begins. Knowing that Polish names get anglicised, a search came upon Stanislaw Josef Brzeski. Cate seemed to know that he was held in high regard by her grandmother for his exploits, but little else about him; but when I read the biography of him my chin almost hit the floor. She had no idea who this guy was. Interestingly for me, he was buried not far from where I live. This is the story of Stanislaw Brzeski.

Stanislaw Josef Brzeski was born April 21st 1918 in the village of Lipnik, in eastern Poland, to parents Franciszek and Maria. I have no idea whether Stanislaw was from a military family, but in 1932 aged about 15 he joined the Infantry NCO school for minors at Nisko. After graduating in 1935, he was assigned to the 77th Infantry Regiment in Lida. In 1936 he volunteered for pilot training, and completed glider training in Ustianowa, a basic flight course with the 5th Air Regiment, and a fighter pilot course at the Flying School of Gunnery and Bombardment in Grudziadz. He would complete his basic flying training with the 5th Air Regiment and went on to advanced pilot training. By November 23rd 1937 he was a fully fledged pilot; such was his prowess that in 1938 he was a member of the 5th Air Regiment team in the Polish Fighter Air Force Contest at Torun, winning 1st place. I’ve no idea if a dashing young fighter pilot in Poland watched that 1937 musical comedy, or whether he’d found love by then, but he had more pressing duties. Hitlers Nazi Germany was on the rise, Stalins Russia was mobilised, and war was about to arrive. Stanislaw was by now a pilot with the 152nd Fighter Escadrille.

In his free time, he attended a preparatory course for the final exams, but the beginning of the war made it impossible for him to complete. On September 1st, 1939, the German army invaded Poland, the official start of World War II. With the 80th anniversary of the invasion upon us, it’s important to remember the Polish efforts to resist the German & Russian assault. 152 Squadron was in Szpondów and was part of the Modlin Army and immediately involved in fighting the invasion forces in the defence of Warsaw against the Luftwaffe. On September 3rd the army was ordered to destroy a German observation balloon, which commanded artillery fire (firing caused significant losses in the troops of the Mazovian Cavalry Brigade). Because many pilots wanted to be involved in the operation, the squadron commander apparently ordered a drawing of lots: Stanislaw won. He took off and over the town of Grudsk encountered a balloon protected by three Messerschmitts. He destroyed it undetected, and safely returned to his base. The next day he took part in bomber escorts with the 41st Reconnaissance Squadron. On the way back, together with 2nd lieutenant Bury-Burzymski, he saw and attacked another observation balloon. Despite heavy defences he engaged the target but Stanislaws aircraft was hit in a fuel tank, the leaking fuel forcing him to land. He landed in a field near Ciechnowa, apparently making his escape by bicycle!

On September 9th, he was over Lublin flying against German Heinkels of unit KG1. The Poles heavily damaged one plane, which crashed on the German side of the front. On September 17th, on the first day of Soviet intervention, Stanislaw evacuated with his squadron to Romania – he crossed the border at night on 18th September. Then, probably from Yugoslavia, he sailed to France – arriving there on November 19th. The evacuated Polish forces took some time to reorganise, but on assignment by the Free French, on May 18th 1940, he was directed to the Groupe de Chasse II /1, commanded by Capt. Franciszek Jastrzębski. From May 20 to June 22, he took part in combat flights on Bloch MB-152s, however he did not win any air victories. On June 23rd, as France fell, he reached Port-Vendres and sailed to Oran, Morocco. From there, he was evacuated through Casablanca to Gibraltar and then to Britain. It was suggested that Stanislaw ‘walked to France’ but this clarifies the story. A brilliant, far more detailed account of Polish Airforce operations in the first days of the German invasion, created by Grzegorz Mazurowski, including actions by Stanislaw, is included here: “Condors from Wilno”

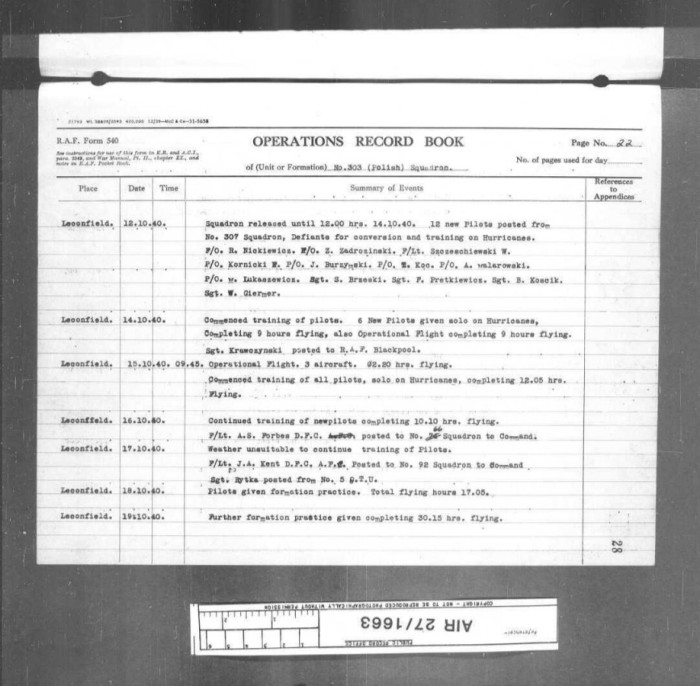

He arrived in Britain on July 7th. By now, Britain was on its knees. It’s army had been evacuated from Dunkirk and the Battle of Britain was yet to start. Grateful for all the help it could get, Polish airmen were assimilated into the Polish Air Force, but initially were not assigned many fighter pilot roles. There’s considerable evidence of the RAF being dismissive of Polish pilots. Issued service number 782107 in the fledgling Polish contingent, this clearly irked Stanislaw and his compatriots, many of whom were already battle hardened. After all, Stanislaw had been fighting in the skies above his homeland an entire year before the Battle of Britain reached its climax. Posted to 307 City of Wilno squadron on 10th September, he was soon involved in a ‘mutiny’ after being given flights flying the sluggish Boulton & Paul Defiants, not the fighters he craved. By October he was moved to No1 School of Army Cooperation at Old Sarum in Wiltshire, then to No5 OTU to convert to the Hurricane, and by October 12th to 303 Squadron at RAF Leconfield. He was briefly with 245 Squadron RAF and by 9th December to the illustrious 249 Squadron. Flying from RAF Church Fenton near Tadcaster, the station was a melting pot of squadrons of all nationalities, and the fighter squadrons would deploy from there to other bases.

On 25 February 1941 he joined the newly formed 317 Squadron at RAF Acklington near Morpeth in Northumberland, and would then fly from RAF Ouston in County Durham. The picture below shows Stanislaw with ‘B’ Flight three days after reaching operational readiness.

It was the posting to Northumberland that would prove pivotal for him, and would be where the conversion from Stanislaw to ‘Uncle Stan’ would begin. There are no facts available to tell us how a young fighter pilot enjoyed his spare time in Northumberland, but it can be imagined that Acklington and its surrounds in the rural north held few enough interests to cause him to venture out to the nearby towns for entertainment. Whether Stan frequented the market town of Morpeth or thereabouts, it was at a dance in the Sergeants Mess at Acklington that Sheila Allison first set eyes upon the young Hurricane pilot. Stan had returned from night flying when he walked into the room, and was still in his flying suit; tall, dark and handsome. Sheila was cousin to Cate’s grandmother, or ‘Aunty Sheila’ as she was known to Cate. Who knows who saw who first in those early months of 1941, but it was a love that would endure.

They were of a similar age; she slightly younger than him, born in Bedlington, Northumberland in July 1920. In reality they were from separate worlds. In any case, an impression was made, and soon the story goes that Stan was buzzing her house in the nearby pit town of Ashington in his plane!

Stan had already claimed his first ‘kill’ by February that year, so in pilot terms was on the road to becoming a celebrated ace. I can only imagine the tales that would be told in the pubs and dance halls around Morpeth to wide eyed girls. He would claim Sheila’s heart, too.

317 Squadron would claim their first victory on June 2nd 1941, with the shooting down of a Junkers 88 over the mouth of the River Tyne. The pilots were greeted like heroes on their return, and 317 celebrated like they’d won the war itself.

However the love affair between Stan and Sheila developed, by June 1941 he was gone again as 317 Squadron moved south, alternating between offensive and defensive operations over France or the English Channel. Infrequently, he would return north, but it’s obvious that their bond was strong. By October Stan had converted from Hurricanes to Spitfires; Sheila was undoubtedly worried for her young man fighting out over the English Channel and occupied France. Although separated, Stan was determined to keep her with him, by painting her name on the cockpit of his aircraft.

They married at St Robert of Newminster Roman Catholic church in Morpeth on March 20th 1943. I’m unaware of the time the young couple spent apart, although after marriage there’s evidence that Sheila moved south to be nearer to him.

Stan would go on to become an ace pilot. He would go on to be accredited with fourteen victories: either confirmed, shared, ‘damaged’ or ‘probables’- and truly among the greats of Polish fighter pilots. However, it was not all glory for Stan, as tragedy crossed his path in February 1942.

On the morning of February 15th, Stan and fellow pilot F/Sgt Jan Malinowski were instructed to intercept an unidentified aircraft in the western approaches south of the Eddystone Lighthouse. Flying from RAF Exeter, their target was in fact a British Liberator, AM918, on a direct flight to England from Cairo operated by BOAC. The aircraft had been on return ferry duties to North Africa. Among the nine souls on board were three senior military officers; Brigadier Frederick Morris CB RAOC, Lt Colonel Townsend Griffiss USAAC and Lt Charles Vine RNR. Griffiss was the first American officer killed in Europe after their entry into the war just weeks earlier.It was later clear that the two Spitfires had been instructed to intercept and shoot down the potentially hostile aircraft if necessary. Confusion among flight controllers, lack of identification skills by the Poles, and an incorrect response from the Liberator crew led to disaster. Despite the tone of the above communication, subsequently the Board of Enquiry exonerated the pilots of blame.The biography of Townsend ‘Tim’ Griffiss can be read here: Townsend Griffiss

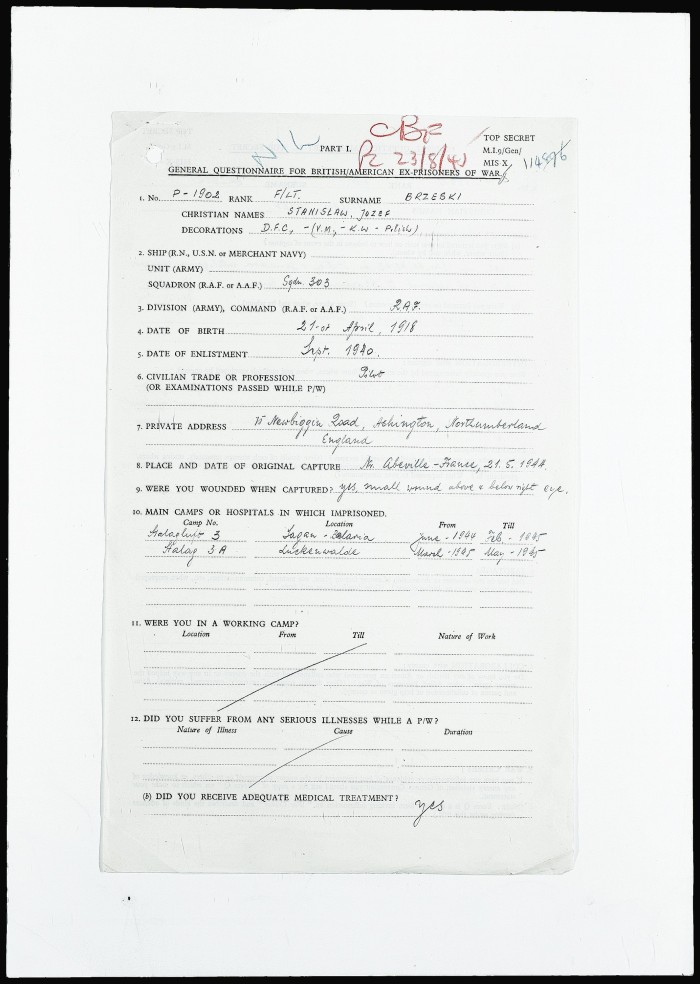

Whatever the emotional cost to Stan, the tragic events of that February morning did not affect his career. On June 1st he was commissioned as an officer, and in September became an instructor at 58 OTU RAF Grangemouth in Scotland, and also with Rolls Royce in Derby studying the engineering of aircraft engines. However, by April 1943 he was back flying Spitfires operationally with 302 Squadron, and then by December 28th back to where he began – as ‘A’ Flight commander with 303 Squadron, and continued to cement his reputation as an ace. Stan’s luck finally ran out just before ‘D-Day’ on May 21st 1944 when he was shot down near Abbeville in France. Wounded, he managed to put his aircraft down, but after a few hours on the run, fell into the hands of the enemy. Stan saw out the war in a series of Prisoner of War camps, being moved as the allies advanced deeper into Germany. He was liberated by Russian forces from Stalag Luft IIIA at Luckenwalde on April 22nd 1945.

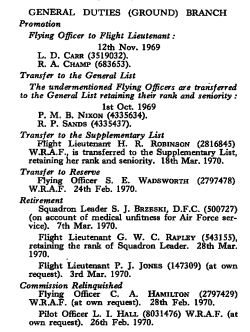

On return to Britain he rejoined as an instructor with 16 (Polish) Service Flying Training School at RAF Newton, then the RAF where he became an air traffic controller until his retirement, latterly as a Senior Air Traffic Controller at RAF Luqa, Malta. The London Gazette of March 1970 gives the reasons for his retirement as ill health; apparently a legacy of his detention in the POW camps.

London Gazette

When Cate posted her original fond memories of ‘Uncle Stan’ she had no clue about this man that her memory longed for. This snapshot of his life story doesn’t come close to telling the full story of his achievements as a soldier and airman fighting for his and our freedom. A military historian would be able to piece together in great detail the exact events from Squadron occurrence books and and combat reports held within the National Archives, and the personnel files of the RAF; but that is a major project beyond the scope of this blog. A flavour of what’s recorded is here:

However, let’s reflect on the awards he received – the reason my jaw dropped when I first realised who he was:

He was awarded The Silver Cross of Virtuti Militari (The highest military award bestowed by Poland and equivalent to the Victoria Cross or Medal of Honor).

He received four awards of The Cross of Valour from his homeland.

He was awarded The Distinguished Flying Cross with two bars.

He was awarded The Distinguished Service Order.

©Dr Tomas Kopanski

Above is the citation for the award of the Virtuti Militari written by Major Edward Wieckowski of III/5 Squadron on November 21st 1939, for Stan’s actions in the September campaign.

The above image shows Stan, rear right, recognisable by his jaunty cap angle. A 10 month old baby was the central figure at the ceremonial parade. The child – Marian Edward Bełc, son of Pilot Officer Marian Bełc – received the Distinguished Flying Cross awarded to his father, killed in a flying accident before he could himself receive the decoration. This image dates the award of one of Stans DFCs. Air Commodore W H Dunn is the presenting officer. Marian Belc had been a 152 Squadron pilot and comrade of Stan’s back in Poland at the outbreak of war.

So Stan served almost 40 years in the Polish and British military and left behind an incredible legacy from Master-Corporal to Squadron Leader. Unable to return to Soviet Poland after the war, Stan was naturalised as a British citizen on August 1st 1950. Sadly, his life was shortened by his service and he died at North Elmham in Norfolk on December 3rd 1972, aged just 54, after almost 30 years of marriage. Stan had been a devout Catholic throughout his life and took mass at East Dereham near his home. The legacy of their marriage was two daughters and several grandchildren. Sheila died in 2014 aged 94 in Suffolk, and her ashes were interred with Stan at St Mary’s Church, North Elmham. I finally found Stan and Sheila on a damp July Saturday morning, reunited in the quiet corner of Norfolk they’d chosen for their retirement.

I’ve not researched deeply to find a link between Stan and Douglas Bader, but as an established ace, it’s entirely conceivable that their paths would have crossed once Bader had become prominent in ‘Big Wing’ tactics. Bader was a POW from August 1941 so I’m unsure of the opportunities they had to meet.

As for the love story, whether he ever asked Sheila out at nine, or bought her flowers, took her to a movie and a cafe, then walked her home in the moonlight I guess we’ll never know. Maybe he did ask her out at nine again; I suspect he did, because all we know is that their love endured, and beyond the military legacy, was a legacy of love and charisma that impressed itself on Cate.

To the memory of Emanuel Schlecter, Janowska Concentration Camp

I am indebted too to Cate Moore, for access to family photographs that add so much to the history of Stan and Sheila.

If you are interested in further reading about the people of Poland and their experiences of the 20th century under Nazi and Soviet rule, the Witold Pilecki Institute in Warsaw have a resource of materials here: Chronicles of Terror

All Copyright acknowledged where not identified. Sources include: The Tomas Kopanski Collection, iwm.org.uk aviationart.pl polishairforce.pl cieldegloire.com East riding.gov.uk and others.

Great to read. Thanks. I now live near Torun in Poland, My connections with Poles goes back to being at school in Uxbridge with a boy I now suppose to have been the son of one of the pilots of 303. It’s a small world. As incidentals, the politician Airey Neave, who was murdered in Westninster in 1979 by the IRA, was a PoW here in Torun. The old wooden hangars still exist in Grudziadz, I flew in a glider there once. I wonder if we can protect the legacy of democracy the Poles were so crucial to giving us. Poles know the full price of freedom, but I fear we Brits have always been too insular to understand as well as they do. .

LikeLiked by 1 person

Look your friends father up here https://listakrzystka.pl/en/polskie-sily-powietrzne-na-zachodzie/if you know his name

LikeLike

Stan Brzeska is my paternal grandfather! Loved this article !!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi, I’m glad you enjoyed it! I’ve been talking to Cate Moore, who’s related to Sheila. If you don’t mind, what’s your name, I’ll let her know. She’s equally proud of him and remembers him from when she was little

LikeLike

I loved seeing all the pictures of my great grandfather I’m very proud of him winning the purple cross, my favourite picture was when he got awarded

LikeLike

Stan is a great subject to write about

LikeLike