I’ve blogged previously about ancestors who left the fields of Norfolk to fight in the Great War, and been able to point to events where those young men felt compelled to answer the call of King and Empire; some who were recognised for bravery, others who fought a long and dedicated war, and some who paid the ultimate price. This blog paints an entirely different picture of suffering. It’s all too easy to think of conflict in terms of soldiers gallantly facing an enemy in combat and taking their chances on whether they’d survive. The story of William Hinnells is altogether different.

William is related to me by being the brother of my great grandmother Emma Cole. Emma was the eldest daughter of William Snr and Elizabeth Hinnells, and was born in Kenninghall. By the time William Jnr was born on June 16th 1891, the family was living at Gasthorpe near Thetford and further children Alice, Sarah and Queenie followed. William Jnr was baptised on July 10th 1892 at Riddlesworth. The youngest, Queenie, was born in 1897 and at which time the family was living at Tasburgh, south of Norwich. William Snr was described as a ‘Horseman’ and as was common with farming in those days, men would move to wherever there was work, or if with a growing family, wherever there was the chance of a bigger cottage.

The census of April 1911 placed the family living at The Green, Salthouse on the north Norfolk coast. I can’t quite place the exact cottage which is described in the census as on Holt Road (now Purdy Street) but it’s one of those next door to the Dun Cow pub. The picture of Emma above was taken at Salthouse. Quite what caused such a shift from Tasburgh is unknown, but the by now 19yr old William Jnr was recorded as working in a stone pit, probably in the pits among the Bronze Age burial mounds on Gallows Hill or thereabouts. I can’t imagine digging flint or gravel from the north Norfolk ridge was the most inspiring career for a young man, which perhaps explains the fact that the next we hear of William is in 1915 and he is in Calgary, Alberta, Canada. In my first blog about Harry Crook and his brothers, I’ve mused about why farm boys left Norfolk for Canada. The Dominions Land Act of 1872 clearly attracted young men with aspirations of striking out on their own, with the promise of 160 acres and a fresh start. As with the Crook boys, I’ve no idea what sparked the interest in William.

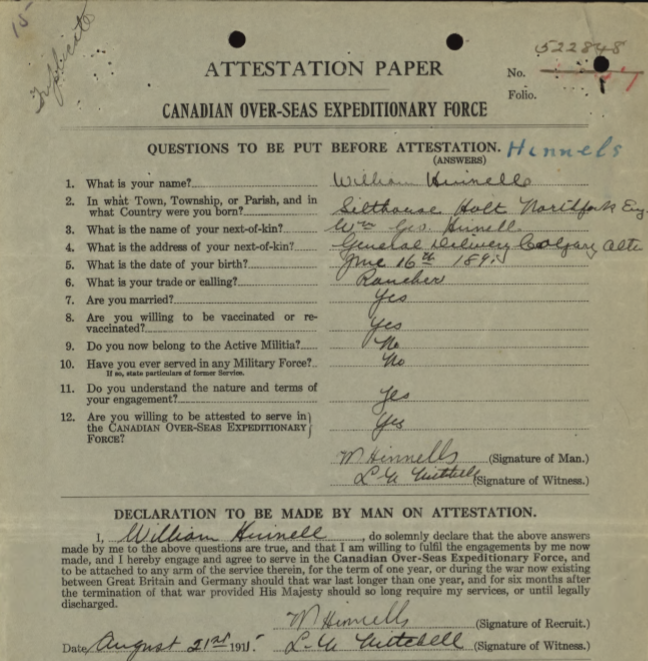

I’ve got no information about exactly where William settled in Alberta, other than he made the trip to Canada in April 1913, from Southampton via Portland, Maine. By 1914 he was married to Helen Bentley in Calgary, who gave birth on 7th July 1915 to a daughter Queenie Irene, named after his youngest sister. His occupation was given as ‘rancher.’ I know nothing about Helens origins, whether she was originally British, American or Canadian, but she was born in 1894. By now, Canada had provided many men for the Great War, and the Canadian Expeditionary Force had entered the conflict in the early weeks of the year. The initial drafts had been made up of many men from the old country, so I suppose it was difficult for young able bodied men like William to avoid the call to arms. On August 21st 1915 William enlisted at Sarcee Camp in Calgary. Helen was 21 and Queenie was six weeks old. William, aged 24, was on his way back to Europe.

William was enlisted into the Canadian Army Medical Corps. I have no idea how selection took place for fighting units, but on his attestation papers, William is described as 5′ 11.5″ tall with a 36.5″ chest, brown hair and hazel eyes. Although I have no picture, I can see a tall slender youth, perhaps too slender to be a soldier, and perhaps someone decided he was best suited to a non-combat role. It would make no difference to the outcome of his war.

By November 4th 1915 Private 522848 Hinnells was ‘overseas’ which for so many ‘new’ Canadians meant the journey back to England and the transit camp at Shorncliffe near Folkestone in Kent. By December 3rd he was taken on to the strength of the 1st Canadian Field Ambulance, part of the 1st Canadian Division, and by March 6th 1916 found himself at Bailleul in northern France. Their diary describes their strength as 5 officers and 255 other ranks. Coincidentally, the 1st Division also included the 5th Canadian Infantry (Saskatchewan Regiment) who had among their number my great uncle Sidney Crook, as mentioned in my previous blog. We think of soldiers going to the front to fight, and all the dangers and hardships associated with life in the trenches, but I wonder what William made of his role – working behind the lines supporting the fighting men, but going up to the lines where the advanced dressing stations were positioned, to collect the wounded or the dead and dying to remove them further back to the field hospitals, or onward back towards England. By April 7th he was in ‘the field’ dealing with the horrors of war.

I reflect upon that, because a few weeks later the 1st Canadian Division were in the line holding the bitterly contested ground at Hill 60 near Ypres. Sidney Crook was there with the 5th as the Battle of Mount Sorrell kicked off on June 2nd. His position came under heavy bombardment on the afternoon of June 6th, and it is during that action we assume he received the shrapnel injuries leading to his death the next day at Casualty Clearing Station 10 at Remy Sidings near Poperinge, which is the site of what is now Lijssenthoek Cemetery where he is buried. As I’ve studied the history, it seems an odd quirk of fate that it could have been William and his colleagues who went forward to retrieve a mortally wounded Sidney. Their diary is reasonably perfunctory in that it deals with heavy numbers of casualties coming back from the front, and also their own men being affected by shelling. The thought of two unrelated forbears crossing paths in that way intrigues me. Their position in that period was at Bedford House, which is now also the site of a cemetery. They were operating between places like Transport Farm, Bedford House and Vlamertinghe Mill, feeding the wounded back to Poperinghe and beyond.

In August 1916 the 1st Field Ambulance held a sports day to relieve the stresses of battle and improve morale in what had been a tough period for the Canadians. Reading the reports on the work of the ambulance battalions and field hospitals, they were very much exposed to the risks of the front, working within range of the enemy; even the hospitals came within scope of the guns as the front changed position.

1917 saw a downward turn in Williams health, and saw a chain of events begin that would change everything. On 23rd April he was admitted to No 3 Canadian General military hospital at Dannes-Camiers and was given a diagnosis of ‘VDH’ which on face value sounds like the discovery of a valvular heart disorder, but when you look closer you realise there was a condition which became know as ‘Soldiers Heart.’ Without departing into a paper on cardiac disease, this seems to be a number of conditions brought on by stress and exertion leading to potential rheumatic disease of the heart. Today we’d call it Da Costas Syndrome, the physical manifestation of an anxiety disorder. A study at the time of 400 men revealed no presence of any disease in 90% of them; the condition was a form of PTSD causing the symptoms of a heart condition. William was taken off strength and invalided back to England. He seems to have recovered somewhat as he was discharged and back in France at Etaples on July 3rd, but by 10th December he was taken off strength from his depot again and was obviously unwell. 19th December shows him at Fort Pitt Military Hospital, Chatham. The diagnosis was acute appendicitis and by 21st he underwent surgery.

From then on in his medical notes make sorry reading. On 17th January he was listed as ‘dangerously ill’ and made slow progress through February. The medics had been testing for TB but found nothing. By March 5th he was off the danger list. He continued to convalesce in England but pain and tenderness in his chest persisted. June saw a second surgery. Infection was present and an abcess had formed on his lung. William was again weak and in a fragile state. He remained in hospital at Woodcote Park Convalescent Hosptal at Epsom, Moore Barracks at Shorncliffe and in September back to Woodcote Park. By September he was again complaining of pain in his chest and leg. Bronchitis like symptoms were persistent and on 16th November, just five days after the wars end, William was dead. By now he had been transferred to Tranmere Auxilliary Hospital at Birkenhead; as close as he’d ever been to Canada since leaving in November 1915.

Today, post operative infection and subsequent blood clots leading to pulmonary embolism and an abscess on the lung are probably better understood, and pulmonary tuberculosis an ever present threat. In any case, TB was given as his final cause of death Whether ‘Soldiers Heart’ was a genuine diagnosis of a condition brought on by the terrible conditions of war, or an actual heart defect, I don’t know. Either way Williams death seems so much sadder than any of his comrades who died as a result of enemy action on the front. Sadder still that this farm boy from Norfolk travelled to Canada to make a new life, but had to leave a young wife and baby daughter behind. As far as I can tell, he never saw Helen or Queenie again once he left in 1915. His papers show that Helen had moved to Portland, Oregon after the war, where she died in 1979. Maybe that’s where she came from.

As for his daughter, Irene as she chose to be known, lived until 1994. She married an eminent biochemist Vernon H Cheldelin and there is a record of her visiting England in the 1950’s. She became a scientist in her own right. Her obituary is here:

Obituary of Irene Hinnells Cheldelin

I wonder if she ever visited Salthouse to see the grave of the father she never knew?

One day I’ll get round to researching the Canadian end of the Hinnells story, but for now the tale of a farm boy and how a war broke a familys heart is where we stop.

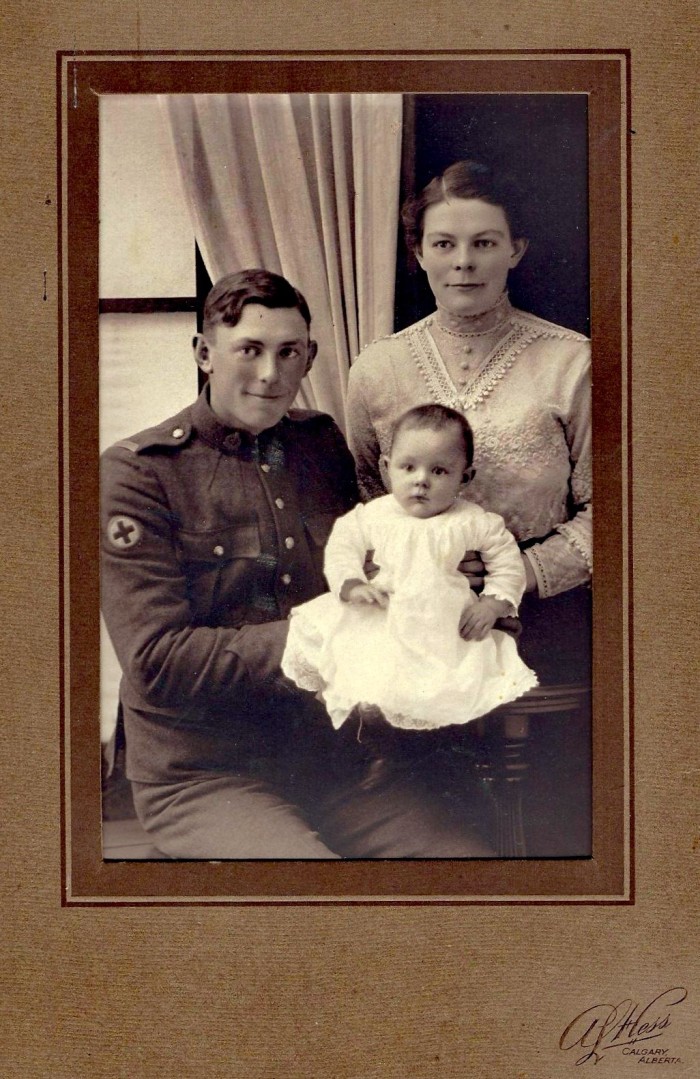

Addendum. October 2020: almost three years after posting this blog, I was contacted out of the blue by Larry Cheldelin, grandson of William Hinnells, who lives in Oregon. He provided me with the above photograph taken some time in the autumn of 1915 very shortly before William embarked to England. Larry was able to confirm that on embarkation to England, William never saw his young family again, and that Helen never remarried, raising Irene alone. Irene would go on to marry Vernon Cheldelin, and raise a family, of which Larry was one.

Sadly, Helen had never known the truth behind her husband’s death.

Irene had visited England on a sabbatical with her husband in 1953, and visited her father’s grave at Salthouse, which ties in with a memory of a story known by my father that ‘family from America’ had visited when he was a child. Larry confirmed that the above photograph was taken only days before William and his family were separated forever.

I am the son of Irene Hinnells. William was the grandfather I never knew. Mom and the rest of the family did visit Williams grave in 1953 when dad was on sabbatical to Oxford. William never saw his wife or child after leaving Calgary for the war. Thank you so much for this history. We never knew what happened to him other than he died. His wife never remarried and raised Irene on her own leaving Calgary to move to Portland, Oregon.

Larry Cheldelin

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Larry, what a great connection! I’m guessing that makes us somehow related as William was brother to my great grandmother. Williams grave is not too far from me and I can visit it from time to time. If the family wish to know more I can help

LikeLike

I forgot to mention, it would be great to see a picture of William if the family has one

LikeLike

Hi Larry, my husband is great nephew to William. His middle name is Hinnells.

William had 3 sisters. Elizebeth being 1 my husbands grandmother.

LikeLike

I do have a single photo of William with his wife (my grandmother) with their infant daughter the day he left. She would never hear from him again and did not find out until a longtime after he died that he had passed. She was never informed what he died from. She left Calgary October 19th 1919 and came to Oregon where she lived until her passing. I will try to send you a copy of the photo but if it does not come thru please contact me on my e-mail and give me an address to send the photo.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It would make my year if you could send me the picture. I’ve not received anything via email (assuming you’ve tried already) if not, give me your email address and we can converse outside wordpress

LikeLike

my e-mail is cheldeli@nwlink.com

LikeLiked by 1 person

There are 3 of us who share a direct line of Hinnel(ls) from Riddlesworth etc

John Hinnels,m Mary Ransdell , Robert Hinnels b 1808 ,m Emma Lord , Emma Hinnell b 1847,

Did anyone work for Riddlesworth Hall ?

There are other questions I have if anyone picks this up.

My unique cousin did the hard work 56 years ago when aged 14.

The William Hinnells story is touching. And there was a rumour about Canada and USA in our family!,

LikeLike

Hi John, I’ve not researched in detail the Hinnells line beyond my great grandmother and her brother William, but the family has strong connection with the village of Gasthorpe, which is next to Riddlesworth, so there’s every likelihood some of them worked for the estate

LikeLike

I got the name wrong of my husbands grandmother, not Elizebeth but Sarah.

LikeLike